Abstract

Objectives

The standard treatment for short bowel syndrome is home parenteral nutrition. Patients’ strict adherence to protocols is essential to decrease the risk of complications such as infection or catheter thrombosis. Patient training can even result in complete autonomy in daily care. However, some patients cannot or do not want too much responsibility. However, doctors often encourage them to acquire these skills. Based on qualitative investigations with patients, we wanted to document issues of importance concerning perceptions of autonomy in daily care.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 13 adult patients treated by home parenteral nutrition using a maximum variation sampling strategy. We proceeded to a thematic analysis following an inductive approach.

Results

After achieving clinical management of symptoms, a good quality of life is within the realm of possibility for short bowel syndrome patients with home parenteral nutrition. In this context, achieving autonomy in home parenteral nutrition could be a lever to sustain patients’ quality of life by providing better life control. However, counterintuitively, not all patients aim at reducing constraints by reaching autonomy in home parenteral nutrition. First, they appreciate the social contact with the nurses, which is particularly true among patients who live alone. Second, they can feel safer with the nurse’s visits. Regaining freedom was the main motivation for patients in the training program and the main benefit for those who were already autonomous.

Conclusions

Medical teams should consider patients’ health locus of control (internal or external) for disease management to support them concerning the choice of autonomy in daily care for parenteral nutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure (SBS‐IF) is a rare, chronic, life‐threatening condition. By definition, patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS) have a remaining functional postduodenal small bowel length of <200 cm. The true incidence and prevalence of SBS among adults are unknown. In Europe, among adults, the prevalence of SBS varies by region, from 0.4 per million in Poland to approximately 30 per million in Denmark [1] and 34 per million in Germany [2]. The standard treatment for intestinal failure due to SBS is home parenteral nutrition (HPN).

SBS may result from various causes, such as extensive surgical resection due to Crohn’s disease, mesenteric infarction, surgical complications, radiation enteritis and abdominal trauma. Following intestinal resection, if the absorptive capacity of the remaining intestine is not sufficient to provide macronutrients, fluids, electrolytes, and minerals to sustain life, then the patient experiences intestinal failure (IF). Therefore, patients with SBS and IF require parenteral support, which provides nutrition and hydration requirements intravenously. SBS-IF is associated with a decrease in survival due to complications related to SBS and/or parenteral support (PS), such as catheter-related sepsis, kidney disease and liver issues. The main goal of physicians is to reduce PS dependency to reduce complications and increase quality of life. Additionally, it is essential to promote the adaptation of the residual digestive tract by maintaining an oral diet, by carrying out rehabilitative surgery, and possibly by using trophic factors such as GLP-2 analogs [3, 4].

Studies that document issues of importance from patients’ perspectives has been conducted since the early 2010s [5]. The first most important observation pointed out the perception of limitations to act spontaneously [6]. Adjustments to lifestyle restrictions by way of acquiring new value in life were also highlighted [7]. Patients even expressed a strong desire to achieve normalcy in life and sometimes made a positive description of their quality of life [8]. Patients underlined that major aspects of need affected by HPN were autonomy, relationships, role fulfilment, socialization, appearance and self-esteem, appetite and perceived vulnerability [9].

Patients’ strict adherence to protocols and close monitoring of aseptic techniques regarding catheter care are essential to decrease the risk of complications such as infection or catheter thrombosis [10, 11]. Patient training can even result in increasing patients’ participation in self-care up to complete autonomy in daily care for HPN [12]. How to disconnect or connect the line from the catheter alone can be an educational objective allowing the patient to be completely independent [13] that could influence their quality of life. However, recent HPN surveys indicated that nearly 50% of patients are autonomous [14]. Some patients cannot or do not want to take on too much responsibility. However, doctors often encourage patients to acquire these skills.

Several institutions throughout North America and Europe have developed intestinal rehabilitation programs that consist of comprehensive interdisciplinary teams dedicated to the management of patients with IF. A fundamental barrier to the involvement of a team based approach in US is the limited number of IF centers available. Since the mid-1990s many of these programs had been involved with continuity of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting [12]. Ensuring patients are competent at catheter care and HPN management is a key component for long-term care with no difference for patients trained in hospital or at home [14].

In France self-management for autonomy in HPN are delivered for the adults in approved (reference) hospital centers following a multidisciplinary approach [15]. The training stops when patients achieve required skills for HPN that begins only when following a formal pedagogical assessment. After a transition period, there is no regular nurse visit at home except for the implantation of a needle in the port, if necessary. Family caregivers of adult patients can be educated in safety actions but exceptionally, in adults, to disconnect or connect the line.

Research findings are clinically relevant for guiding clinicians who are responsible for treating patients [16]. Based on qualitative investigations with patients, we wanted to document issues of importance concerning (1) the main determinants of quality of life among patients with HPN in SBS and (2) perceptions of autonomy in daily care.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive qualitative study was undertaken to provide an overview of possible postures for patients concerning autonomy in daily care for HPN. The present study was carried out in compliance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [17].

Sampling and recruitment

Semistructured individual interviews were conducted with adult patients with SBS treated by HPN. All patients were cared for at the Transversal Nutrition Unit in Nancy, which is the unique reference center for the whole East quarter of France. The unit treats an active file of 127 in 2021.

Sample heterogeneity is considered essential to capture in-depth and large amounts of content in qualitative studies. To maximize variation sampling [18], we identified several dimensions of variations: sex, age, marital status, duration of SBS and HPN and the presence of a stoma.

A number of interviews ranging from 11 to 20 corresponds to a satisfactory sample size for qualitative studies to saturate findings [19, 20].

We selected patients who full-filled our variation criteria (sex, age, marital status, duration of SBS and HPN and the presence of a stoma) among the 127 file active list of patients. Then, we invited the chosen one individually providing a mandatory written information. When a patient refused, we returned to the list to identify another with a similar profile.

Data collection

The interview guide was developed based on extensive literature consultation referring particularly to the experience of SBS and HPN from the patients’ perspectives. The health psychologist (LR) proposed the first draft, and then a clinical coordinator of a reference center (FJ), member of the team project refined it. The idea behind the generation of the interview guide was to collect a broad overview of SBS and HPN experiences (Table 1). We also collected demographic and medical information to check the maximal variation strategy previously defined.

From September 2020 to December 2021, an experienced female health PhD psychologist (LR) conducted interviews either during a patient’s hospitalization, after a medical follow-up consultation or by telephone.

Only the participant and the researcher were present during the interview. The researchers did not have any relationship with patients before the start of the study. The interview duration was approximately 1 h. Interviews were integrally audio‐recorded and transcribed. Two patients refused to participate in this study. One did not see the point; the second did not give any particular reason.

Data analysis and rigor

A general inductive approach was followed to identify themes from the patients’ perspectives [21]. We analyzed the data using NVivo 11 software. After a careful reading of the first three interviews, the health psychologist (LR) developed a coding grid. Then, the grid was refined during a meeting with a clinician (DQ).

The health psychologist and an advanced medical student double coded all the interviews. Disagreements were immediately resolved by discussion. Thus, the grid was progressively refined and specified. We applied the same process until the coding grid was completely standardized. In the dataset, Cohen’s κ coefficient between the two coders reached a value of .84. A Cohen’s κ level >.80 is generally considered evidence of reliability [22].

The use of triangulation in qualitative research is considered as the best practice [23]. We applied an investigator triangulation since content of the themes was discussed during 2 meetings with a health psychologist (LR), and 2 clinicians each of them responsible of a reference center for IF in SBS. In this type of triangulation, researchers provide different insights for a deeper and broader understanding of findings.

Interviews were conducted in French but illustrated quotes were translated into English to suit an international audience. Data presented are relevant quotations and ellipsis are used to indicate omitted words/phrases (see Results).

Results

Participants

We recruited males and female for all adult ages. Most of participants were part of a couple. The range of experience with SBS and HPN was from less than 2 years to over 10 years, with a number of days of infusion from one to seven. More than half participants had a stoma bag and underlying diseases of IF due to SBS were classical. Characteristics of our sampling were therefore sufficiently varied for collecting broad perspectives on life with SBS and HPN (see Table 2, for more details).

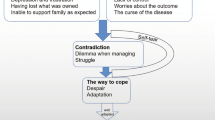

Thematic analysis

Six main themes emerged (see Table 2) from the discursive data: (1) installation of the equipment at home, (2) autonomy in daily care for HPN, (3) care and support in the reference center, (4) quality of life determinants, (5) organization in daily life, and (6) impact of SBS on professional life and financial aspects of the disease. In the present paper, we chose to focus on perceptual contents referring to quality of life determinants and to autonomy in daily care for HPN (see Table 3).

Table 3 provides an overview of the subthemes related to issues of importance for patients’ quality of life and for autonomy in daily care. For each subtheme, we present at least one example below.

Quality of life

Quality of life can be perceived as strongly impacted by:

The need to frequently use the bathroom.

“Twice, three times a night, depending (…) Six times, seven times, at the beginning it was unbearable, at the beginning it was truly unbearable because at the beginning I drank a lot of bottled stuff, now no, now it’s fine.” (P5, W)

“I don’t go to restaurants or even bars anymore because as soon as I swallow something I have to go to the bathroom. I don’t do that anymore.” (P11, W)

“We don’t organize much, well if I go out anyway I mean I have my vehicle if I have to go shopping or sometimes to see my family; after that it’s a rather sad life I would say (…) It’s quickly solved, we have to be honest (…). Well it’s enough that you have diarrhea or something, it’s enough that there are no toilets or something else, well no it sucks. Sometimes it’s all in a hurry, I go shopping, it’s ta ta ta, thank you, goodbye (…) I see my friends, the people I know, I talk a little and then that is it. Yes, no, no, I don’t live in a comfortable home either. However, now it’s not very fun to get drunk either. Inevitably it… It transforms you, the desire to laugh has disappeared.” (P9, M)

The requirement to stay at home.

“There was a huge deprivation. Well, I used to go out a lot in the evenings (…). Anyway, for me, the arrival of the equipment was a great hardship because I could no longer do all that.” (P12, M)

A combative posture by setting realistic and achievable goals sustains a satisfactory quality of life

“I have not changed.” (P4, M)

“I do absolutely everything like other people, I go motorcycling with friends, I go everywhere, I take my daughter to the forest, I ride my bike, I do everything, I do everything. Frankly, I couldn’t tell you that it truly implies something in my life, it wouldn’t be true!” (P7, M)

“I had an unattainable goal of 80 kilos and now I’m at 77. It’s a dream, even at the disease center they told me not to expect so much and I managed to do it. I can do sports, I can go on long hikes and everything is more or less in order. Of course, I depend on the infusions; if I stop for a day, it is not possible (…) I can live quite normally. Of course, I can’t go back to work on a construction site. Let’s just say that I can do the usual things in everyday life, even walking 15 km in the forest.” (P8, M)

“Since this summer I’ve taken up sports again, and this summer I tried hiking, not like before, but in the middle of the mountains in the Alps, so I was quite happy, so now I have taken up tennis again, but in small doses (…). I ‘ve always wanted to play music (…). Well, that’s it, so it has been a little bit of revenge, how can I put it, and so I’ve signed up for violin lessons.” (P13, W)

The team participates in the acceptance process by evoking the perspectives of possibilities for the future

“It was complicated at the beginning, but the doctors taught me to do it gradually, and it was not… Little by little, I discovered that my body was truly modified. That was of course a shock, an acceptance. It didn’t happen overnight (…). My life was going to change completely, and afterward it would be another life so I could technically enjoy it again a little bit but… It’s true that for me it was a nightmare and as the medical staff told me no, no, you ‘ll see, you’ll go back to biking, you’ll go back to skiing. I didn’t believe in it too much (…) and then everything the nurses told me became a reality.” (P3, M)

Autonomy in daily care for HPN

Why refuse?

Some patients, although autonomy seems attainable, do not want it:

For reasons related to contact with the nurse. The need for contact with nurses is most prominent among patients living alone.

“I know that she [nurse] would like me to unplug by myself and all that (…). Because I don’t feel like it, so the nurse comes and we both chat. That’s it. However, I could do it, but she’s there and that’s good.” (P2, W)

“Because the nurses tell me, that’s what they tell me when they come to the house because I prepare everything for them when they arrive (…) And in the morning I even take off my perfume, I close everything, they tell me Mrs… you are even able to do it by yourself (…) Well actually the fact that the nurses are there already gives me someone to talk to (…) Because I’m all alone and in fact it gives me a link.” (P6, W)

For reasons related to the security provided by the nurse’s visits.

Some patients evoked these visits as a kind of safety net to ensure timely referral to health care services if needed.

“That’s why I want the nurses to come because I tell myself if I go too far, I can tell them that it’s not going well, or they can tell me to stop, I have to stop (…). That’s it and for me the nurses are a guardrail because if they see the moment when, if ever there is a moment, because I know that there is always the risk of occlusion, which has several risks and all that.” (P6, W)

“They proposed to me to undergo training and to place the bags but I admit that I appreciate that it is the nurses for different reasons (…). There are periods when indeed, I am not at all in contact with the nutrition service so when it is for long periods I see the nurses.” (P13, W)

Regaining freedom as the main motivation for patients in the patient training program

In our sample, two patients were following a training program to reach autonomy in HPN and were already trained on disconnection. In other words, they knew that competence from a technical point of view was accessible to them.

“I will be able to manage that well if I’m somewhere, if I feel like plugging in at 9 pm it will flow longer in the morning and I will still gain autonomy.” (P10, W)

“The nurses will always assist me until I feel able to do it myself. Then it is going to be a real pleasure, well not a pleasure but an autonomy because I’ll be more free to move around. They gave me a cooler, I have a backpack where I can put my bag and the pump (…) And so with the change of season, the arrival of good weather, I can go out even if I’m plugged in, even if I’m on parenteral nutrition, I can go out of the house; so that’s a freedom.” (P3, M)

Freedom regained as the main benefit for patients already autonomous in disconnection and connection

“Therefore, one year later, I learned how to connect and disconnect my infusions so that I have total autonomy (…) I did it for my autonomy, so that when we want to leave, we don’t have to come back at 1 o’clock because the nurse comes to connect.” (P1, W)

“We had an almost friendly relationship. Nevertheless, we see the nurses more than our own family, it’s always complicated (…) I don’t have home care anymore, I do everything myself, which allows me to live more or less normally (…) connection, disconnection, catheter care, injections if there are any. I’ve been trained to do everything, to be prepared for any eventuality (…) I had to be at home at 6 pm every day until 9 am the next day. It was like that for 4 years (…) To find a little autonomy, especially since I have my wife and my son and they also need to do things. My current life has no restrictions, whereas simply going to eat at a restaurant in the evening was not possible before. To be invited in the evening to see family and friends at 6 pm was the end (…) It will be more than one year that I am completely free. It changed everything.” (P8, M)

Patient latitude in the choice of autonomy regarding HPN

In addition to what patients say is what they do not report. No participant reported elements referring to a refusal for a training pathway for autonomy in HPN that would have been requested by the medical team or of an imposed training that would not have been desired.

Discussion

Much of the available literature in the field of SBS tends to be quantitative, with papers measuring the impact of SBS on patients’ quality of life and associated influencing factors [16, 24, 25].

If physicians try to prevent and treat the main complications of SBS-IF, it is important to capture in depth the resonance of SBS-IF and treatment with PS for patients by using qualitative methods. As already pointed out in the literature, our results underlined that stool frequency affects quality of life in a major way [26]. However, regarding symptomatic control, our findings showed that patients could reach a satisfactory quality of life, particularly when they set attainable goals (i.e., participating in an activity only if requirements were lowered). The medical team can play a pivotal role by supporting patients’ projects [27]. After achieving the clinical management of symptoms, a good quality of life is within the realm of possibility for patients with HPN in SBS. In this context, achieving autonomy in HPN could be a lever to sustain patients’ quality of life by providing better life control. However, counterintuitively, not all patients aim to reduce constraints by reaching autonomy in HPN. First, they appreciate the social contact with the nurses, which is particularly true among patients who live alone. Second, they can feel safer with the nurse’s visits. Finally, for those who have chosen autonomy in HPN, the newfound freedom is key in defining their perceived benefits.

In this context of a lack of knowledge among professionals, our results showed that in addition to strict clinical management, teams could contribute to strengthening patients’ quality of life by not forcing a choice concerning training for autonomy in HPN. In our sample, no patient reported a forced choice concerning autonomy in HPN in one direction or the other. The health locus of control refers to patients’ perception of responsibility for disease management [28]. Some patients want more control (internal health locus of control), whereas others prefer to delegate decisions to the medical team (external health locus of control). In summary, the consideration of the health locus of control could help the medical team tailor the support proposed to the patient [29] concerning the choice of training for complete autonomy in HPN. For the European Medicines Agency (EMA), in 2022, patient preferences “refer to how desirable or acceptable is to patients a given alternative or choice among all the outcomes of a given medicine”. In a recent systematic review [30], assessing patients health locus of control and control preference was established as a crucial determinant to explain patients preferences on health-related decision. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one trying to understand from the SBS patients’ perspectives important issues in proposing autonomy in HPN.

Although we generated and analyzed our qualitative data according to COREQ criteria, there is a limitation in our study since the results are not generalizable using a maximum variation sampling strategy. In qualitative researches, the notion of transferability to other contexts of understanding (analytic generalization) is preferred to the notion of statistic generalization. Maximum variation sampling strategy is one of the key element to strengthen transferability [31]. In France, the support for SBS-IF is usually coordinated by a reference center [15]. The all-French territory has less than 10 approved centers and the one from Nancy covers an area of 5.5 million inhabitants. The fact that we did not recruit patients from different reference centers may have affected the analytic generalization even if we multiplied variation criteria for participants’ profile. Moreover, we applied a triangulation process for findings interpretation in which a clinician responsible of a second reference center in Paris Beaujon Hospital, Paris was included (150 patients in the file active) (see the part Data Analysis and Rigor).

Bias like recall or social desirability are important considerations in quantitative research paradigms. However, these concepts are incompatible with the epistemological concepts underpinnings of qualitative methods [32] in which reliability and validity remain the major criteria for rigor evaluation [33].

Our findings could have been strengthened by further collecting health care providers’ perspectives on factors that might affect their proposition of autonomy in HPN like socioeconomic determinants underpinnings health inequalities such as income, education, and geographic situation [34, 35].

The position concerning autonomy in HPN should not be considered definitive, and the team should be able to assess at regular intervals if the mental load required for autonomy does not exceed the patient’s resources, i.e., to propose a stop-and-go approach as close as possible to the patients’ needs at a given time.

Our qualitative results call for complementary studies on medical team adjustment to patient health locus of control in support of a satisfactory quality of life for patients with SBS.

Taking into account stratification on for example sex, age, HPN duration, or type of central line, it would be particularly interesting to study the impact of initial health locus of control on successful outcomes for HPN in SBS with patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) or even on complications criteria (infection, catheter thrombosis, and metabolic derangement) [36].

Data availability

The data that support the findings are available on request from the authors.

References

Jeppesen PB. Spectrum of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2014;38:8S–13S.

von Websky MW, Liermann U, Buchholz BM, Kitamura K, Pascher A, Lamprecht G, et al. Short bowel syndrome in Germany. Estimated prevalence and standard of care. Chirurg. 2014;85:433–9.

Billiauws L, Maggiori L, Joly F, Panis Y. Medical and surgical management of short bowel syndrome. J Visc Surg. 2018;155:283–91.

Siddiqui MT, Al-Yaman W, Singh A, Kirby DF. Short-bowel syndrome: epidemiology, hospitalization trends, in-hospital mortality, and healthcare utilization. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2021;45:1441–55.

Sowerbutts AM, Panter C, Dickie G, Bennett B, Ablett J, Burden S, et al. Short bowel syndrome and the impact on patients and their families: a qualitative study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33:767–74.

Carlsson E, Berglund B, Nordgren S. Living with an ostomy and short bowel syndrome: practical aspects and impact on daily life. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2001;28:96–105.

Silver HJ. The lived experience of home total parenteral nutrition: an online qualitative inquiry with adults, children, and mothers. Nutr Clin Pr. 2004;19:297–304.

Winkler MF, Hagan E, Wetle T, Smith C, Maillet JO, Touger-Decker R. An exploration of quality of life and the experience of living with home parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2010;34:395–407.

Heaney A, McKenna SP, Wilburn J, Rouse M, Taylor M, Burden S, et al. The impact of Home Parenteral Nutrition on the lives of adults with Type 3 intestinal failure. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;24:35–40.

Harris C, Scolapio JS. Initial evaluation and care of the patient with new-onset intestinal failure. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2019;48:465–70.

Saqui O, Fernandes G, Allard J. Central venous catheter infection in Canadian home parenteral nutrition patients: a 5-year multicenter retrospective study. Br J Nurs. 2020;29:S34–42.

Kumpf VJ. Challenges and obstacles of long-term home parenteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pr. 2019;34:196–203.

Messing B, Joly F. Guidelines for management of home parenteral support in adult chronic intestinal failure patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S43–51.

Bond A, Teubner A, Taylor M, Cawley C, Abraham A, Dibb M, et al. Assessing the impact of quality improvement measures on catheter related blood stream infections and catheter salvage: Experience from a national intestinal failure unit. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:2097–101.

Joly F, Boehm V, Bataille J, Billiauws L, Corcos O. Parcours de soins du patient adulte souffrant de syndrome de grêle court avec insuffisance intestinale. Nutr Clin et Métabolisme. 2016;30:385–98.

Beurskens-Meijerink J, Huisman-de Waal G, Wanten G. Evaluation of quality of life and caregiver burden in home parenteral nutrition patients: A cross sectional study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;37:50–7.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57.

Ames H, Glenton C, Lewin S. Purposive sampling in a qualitative evidence synthesis: a worked example from a synthesis on parental perceptions of vaccination communication. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:26.

Marshall B, Cardon P, Poddar A, Fontenot R. Does Sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in is research. J Comp Inf Syst. 2013;54:11–22.

Mason M Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. FQS [Internet]. 24 août 2010 [cité 4 mai 2021];11. Disponible sur: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1428.

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:398–405.

McDonald N, Schoenebeck S, Forte A. Reliability and inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: norms and guidelines for CSCW and HCI practice. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2019;3:72:1–72:23.

Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:545–7.

Nordsten CB, Molsted S, Bangsgaard L, Fuglsang KA, Brandt CF, Niemann MJ, et al. High parenteral support volume is associated with reduced quality of life determined by the short-bowel syndrome quality of life scale in nonmalignant intestinal failure patients. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2021;45:926–32.

Jeppesen PB, Shahraz S, Hopkins T, Worsfold A, Genestin E. Impact of intestinal failure and parenteral support on adult patients with short-bowel syndrome: A multinational, noninterventional, cross-sectional survey. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2022;46:1650–9.

Parrish CR, DiBaise JK. Managing the adult patient with short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N. Y). 2017;13:600–8.

Ricci L, Villegente J, Loyal D, Ayav C, Kivits J, Rat AC. Tailored patient therapeutic educational interventions: A patient centred communication model. Health Expect. 2021;25:276–289.

Nazareth M, Richards J, Javalkar K, Haberman C, Zhong Y, Rak E, et al. Relating health locus of control to health care use, adherence, and transition readiness among youths with chronic conditions, North Carolina, 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E93.

Marton G, Pizzoli SFM, Vergani L, Mazzocco K, Monzani D, Bailo L, et al. Patients’ health locus of control and preferences about the role that they want to play in the medical decision-making process. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26:260–6.

Russo S, Jongerius C, Faccio F, Pizzoli SFM, Pinto CA, Veldwijk J, et al. Understanding patients’ preferences: a systematic review of psychological instruments used in patients’ preference and decision studies. Value Health. 2019;22:491–501.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1451–8.

Galdas P. Revisiting bias in qualitative research: reflections on its relationship with funding and impact. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1609406917748992.

Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2008;1:13–22.

Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, Ramey CT, Martin EK, Perry C, et al. Social determinants of health in the united states: addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6:139–64.

Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27106.

Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Rausa E, Invernizzi P, Braga M, Vecchi M. Understanding short bowel syndrome: current status and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:253–61.

Acknowledgements

We thank Justine Krier and Martin Clement Sonia –RN- for their help in the recruitment process. We acknowledge the work of Emilie Culminique and Sandrine GrandClere for contributing to transcription and the contribution of Yacine Haroun in encoding the data. We also thank Marjorie Starck for her help in administrative management of the project.

Funding

LR received a Baxter award delivered under the auspices of la Société Francophone de Nutrition Clinique et Métabolisme (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LR, FJ and FG contributed to the conception and design of the research. LR, AC and DQ contributed to the acquisition of data. LR, FJ and DQ helped interpret the data. LR wrote the original draft. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP (Sud-Ouest et Outre-Mer III)) approved the protocol (no. ID‐RCB: 2019‐A0203453‐46). All participants gave their oral consent and received an information and opposition form.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricci, L., Joly, F., Coly, A. et al. Important issues in proposing autonomy training in home parenteral nutrition for short bowel syndrome patients: a qualitative insight from the patients’ perspectives. Eur J Clin Nutr 78, 436–441 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01415-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01415-x