Abstract

The trend of immersive theatre, which began in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and has quickly established itself in contemporary mainstream theatre, is a subset of the larger phenomenon of emerging immersive experiences, which has expanded into a variety of fields, including healthcare, marketing, and education. This paper aims to provide a revised conceptual framework from the context of design through technologies with an addition of bodily immersion, or a sensation of bodily transference, creating illusory ownership over a virtual body, and activating praesence, a lived experience of the physical body responding within an imaginative, sensual environment, produced with the help of immersive technology. This concept, taken from the field of theatre and performance, is combined with four other components (systems, spatial, social/empathic, and narrative/sequential) to produce an immersive experience that realises the fullest potential of immersion. The proposed framework serves as a valuable guideline for creating immersive experiences across multiple disciplines, benefiting both creators and participants by enhancing comprehension and setting expectations. Additionally, it can be utilised by academics and students as a criteria for evaluation and analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While the word ‘immersive’ was first used together with ‘theatre’ in the first decade of the 21st century in the UK, and ‘immersive theatre’ had already become an established style in Europe and America, it was only in 2019 that a small group of the Thai art-goers and theatre audiences had a chance to participate in an event that was described as an ‘immersive theatre experience’ in Bangkok Theatre Festival 2019. The show, called ‘Unless’, was created by Canada-based Single Thread Theatre Company, in partnership with Bangkok 1899, a cultural and civic hub, and Matdot Art Centre.Footnote 1 A year later ‘Save for Later’ by Thailand’s FULLFAT Theatre, which was promoted as a single-audience show wherein one viewer was engaged by performers throughout the play, created a lot of buzz about this trendy ‘immersive theatre’ experience.Footnote 2 With their 2021 production of ‘Siam Supernatural Tour,’ which had audiences wandering around every room of the Siam Pic-Ganesha Centre of Performing Art at night, FULLFAT solidified their status as Thailand’s pioneer of immersive and site-specific theatre. There was a total of three paths in this programme, each of which conveyed a separate story about Thai society and culture.Footnote 3

By 2022, not only had immersive theatre received widespread recognition and popularity among the general public in Thailand (albeit primarily as a social media opportunity), with shows like ‘2046: The Greater Exodus: immersive theatre dining event’Footnote 4 (May 2022), ‘Hanuman Su Su!’Footnote 5 (Immersive Theatre for Children), ‘nowhereland. : THE EDEN’Footnote 6 (September 2022), and ‘LUNA: The Immersive Musical Experience’ (November 2022-January 2023), there was also practice-based research conducted by university students (Chatchawan et al. 2022; Inthawat 2021), as well as numerous online articles and interviews on immersive theatre for the Thai audience.Footnote 7 Moreover, interest in immersive events has also increased tremendously. ‘The End is Coming, Immersive Exhibition’ (November 2022)Footnote 8, which aimed to increase public awareness of environmental issues, was sold out on 22 out of 25 sessions, while ‘Van Gogh Alive’, which has been displayed in major cities all over the world, is expected to be attended by 300 thousand people during its four-month run in Bangkok from March 2023.Footnote 9 The immersive art show ‘the Gate Immersive Theater’, created by Seoul-based digital art studio Topos Studio, also ran for three months from December 2022.Footnote 10 These exhibitions employ a combination of virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) to build imaginary environments often in blank empty spaces, without a typical story or plot, or even a performer.

While promoted using the same term, the expectations and subsequent experiences derived from different immersive events could not be more different. As audience members who have attended the immersive events described above, we have noted that the term ‘immersive theatre’, when used in Thailand, denotes a form of storytelling that takes place in a space designed for the audience to wander in, alongside the actors, (almost) without any use of digital technology. This concept can be traced back to earlier forms of immersive theatre, particularly the works of Punchdrunk,Footnote 11 a British theatre company widely considered a pioneer of immersive theatre (See Biggin 2014, Gezgin & Imamoğlu 2023, O’Hara 2017). Their works were often described as site-specific, or ‘designed for specific, already existing spaces, be it an interior or exterior area’ (Gezgin & Imamoğlu 2023, 3). Furthermore, the immersive theatre experiences that have been offered in Thailand so far align with the four types of immersive theatre outlined by Warren (2017, x-xiii), which include exploration theatre, guided experiences, interactive worlds, and game theatre. All these forms present physical settings containing tangible artifacts, despite differences in design considerations, complexity of rules and mechanisms, and audience agency and dependency. On the other hand, immersive experiences in non-theatre settings often incorporate cutting-edge technologies, while the physical environment of the venue holds minimal importance. With such different concepts, how can we reconcile the definition of ‘immersive’ and the experience of ‘immersion’ that results from them?

The catch-all term ‘immersive’ can be problematic for those who create such experiences, as it can be difficult to decide what needs to be included and improved upon for a piece to reach its full potential. In a writer’s guide for immersive storytelling, Kerrison (2022) states that immersive experiences can be ‘emotional and visceral’, ‘playful, immersive, and interactive’, or ‘fun like a virtual reality experience or escape room’ (15–16). They can ‘take form in varying scales, from small intimate rooms to expansive multi-acre lands’ (17) and ‘may not necessarily follow a clear plot or storyline’ (15). It appears that the definition of what constitutes an immersive experience is ever-expanding. So, how can we assess whether true immersion occurs? If the aim of an immersive event is to make an experience as immersive as possible, should there be any guidelines for doing so? This issue led us to explore what it means to be ‘immersive’, and how an experience of ‘immersion’ can be defined in wider contexts of media and communication on a global scale.

In a general context, to immerse means to ‘become completely involved in something [or] to put something or someone completely under the surface of a liquid’ (Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus 2023). However, the meaning of immersion varies in different fields. Most commonly associated with gaming experiences, immersion happens when ‘a player’s thoughts, attention and goals are centred on the game they are playing’ (Biggin 2017, 38). However, Brown and Cairns (2004) assert that even though it is considered an important subject in the game context, ‘it is not clear exactly what is meant by immersion and exactly what is causing it’ (1297). In the field of theatre, Rose Biggin (2017, 27) refers to the experience of immersion in immersive theatre as:

an intense, temporary experience, with spatial and temporal boundaries that are strongly defined and must be adhered to. Immersive experience is both physically and mentally all-encompassing, but its temporary state is also a vital part of its defining quality. Leaving a state of immersion is as distinct and deliberate as going in. You go in; and you come out, changed.

In digital culture, Nelson et al. (2010, 47) describes it as ‘the sensory experience/perception of being submerged (being present) in an electrically mediated environment.’ The presence of technology is crucial for an immersive experience in most literature in the field of media and communications, however, some researchers view immersion as a sense of being caught up in and immersed by the virtual world, while others see it as a technological capability of computer displays to deliver an extensive illusion of reality (Mütterlein 2018; Berkman and Akan 2019; Slater et al. 2009). One of the rationales behind the latter definition is that it is ‘something that can be objectively assessed, based on technical parameters used to describe a system’ (Slater et al. 2009, 195).

As the popularity of immersive experiences grew and expanded into various fields, such as education, marketing, entertainment and psychology, the gaps between the various interpretations of immersion also grew larger, and the current understanding is fragmented. This led scholars Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge (2023) to integrate multidisciplinary perspectives on immersion and present a framework for the design of immersive experiences. Their study resulted in a definition of immersive experiences as:

the acceptance of one’s involvement in the moment that is conceived through multiple senses, creating fluent and uninterrupted physical, mental, and/or emotional engagements with a present experience, with the ability to attain a lasting mental and emotional effect on the user’s post-experience. (11–12)

Even though there are some similarities between the definition above and that of Biggin mentioned earlier, literature and the input of experts in the field of theatre and performance are absent from the study conducted by Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge, as the focus is on the context of design through technology, with examples drawn from the fields of psychology, games and entertainment, education, and human-computer interaction. In addition, it can be argued that their definition (as well as Biggin’s) could be applied to any live theatrical performance, not only those that are labelled as immersive.

In an attempt to construct a definition of immersion that could be applied across a range of contexts, this article aims to build upon the study by Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge, by incorporating perspectives on the concept of immersion from the field of theatre and performance, and propose a revised conceptual framework, which could be used as a guideline on how to create multi- and cross-diciplinary immersive experiences. In addition to being helpful for creators, this framework, together with the clarification on the concept of immersion provided here, is helpful for participants (of immersive experiences) in terms of deepening comprehension and setting expectations before engaging in experiences. It can also be applied by academics and students as criteria for evaluation and analysis. Although the theatrical and entertainment scene in Bangkok, Thailand, served as our inspiration for this study, it is intended to be applicable globally. This study begins with an overview of how the concept of immersion was developed and made possible through numerous performances, experiments, and technologies, particularly in the theatre and communications fields. It then moves on to a discussion of current viewpoints on the notion, before providing a framework for developing immersive experiences.

The development of immersive experiences in the theatre landscape

Immersive theatre scholars, such as Josephine Machon (Machon 2016a, b, 2013, 2009), Adam Alston (Alston 2016a, 2013, 2016b), and Rose Biggin (Biggin 2017, 2020, 2014) point out that one of the most important goals for those who create immersive theatre is to make the audience the centre of a theatrical experience. Audiences, who are not subject to the standard set of norms anticipated from conventional theatrical performances, have been given new titles, for example, ‘audience-participant, playing-audience, guest performer’ (Machon 2013, 74; 2016b, 38), and ‘productive participant’ (Alston 2016a, 5), as they are invited to take on the responsibility of direct involvement within a performance. The audience that used to be passive in traditional theatre is submerged in an imaginative environment that allows all their senses to be engaged and manipulated, as they become involved in the activities inside that environment (Machon 2016b). However, it can be argued that this engagement of the audience is not a new idea, as it has been one of the goals of theatre from the beginning. Machon asserts that the techniques used by immersive theatre practitioners could be traced back to ancient rituals and international performance practices, such as the African dance dramas, the shadow puppetry of Southeast Asia, and the traditions of street performances (Machon 2013, 28).

In the context of contemporary theatre, however, the idea of engaging the audience as active participants started to catch on midway through the 20th century with various forms of experimental theatre that were influenced by Antonin Artaud in a book of essays entitled Le théâtre et son double (1938, translated as The Theater and Its Double, 1958). Works and theories put forth by Jerzy Grotowski, the Living Theatre, and Peter Brook, among others, expanded the notion of audience experience in theatre. They were no longer interested in placing the audience in darkness, being passive and markedly separated from the performers, like in naturalist performances (or in mainstream proscenium arch theatre today). Rather, the audience is invited and expected to be engaged intellectually and critically, like Artaud’s idea of the ‘total spectacle’ (Artaud 1958, 86–87) and Bertolt Brecht’s epic theatre (Turner and Kasperczyk 2022, 107; Alston 2016a, 6), or physically participate and interact, as seen in the Forum Theatre of Augusto Boal, theatre-in-education and pantomime (Biggin 2017, 25). There are also a number of established art forms that focus on audience participation prior to the first immersive theatre production, such as happenings, environmental theatre, installation art, live art, site-specific art and performance (Machon 2013, 30–35; Alston 2016a, 6). Although immersive theatre seems novel and unique to theatregoers in the twenty-first century, its interactive and participatory qualities are not new. It simply is one of the theatrical forms that have evolved over many generations.

Furthermore, James Frieze (2016a, 1-3) asserts that the opposition between immersive and traditional theatre that can be observed within both academic and commercial discourse is oversimplified and not helpful, as it ‘fails to consider the participatory nature of all theatre and performance’. Gareth White (2012) even goes so far as to claim that immersive theatre cannot accomplish more than any other type of performance, and that the ‘realms of experience’ it offers are already available in other kinds of work. Similarly, Marvin Carlson (2012) states that immersive productions that placed ‘seated audiences in unusual surroundings or untraditional configurations […] were not as revolutionary as many of their promoters or devotees have claimed’ (19), referring to promenade theatre, and performance traditions in medieval Europe and ancient Hindu culture. He further argues that the idea of audience liberation is ‘basically an illusion, and that the control of the dramatic worlds remains almost totally in the hands of the producing organisation’ (17).

Immersive theatre was described as only ‘emerging’ (Alston 2013) around the time that White and Carlson wrote their articles. However, by 2016, this style of theatre was already firmly established within the contemporary theatre landscape in the UK, USA and Europe. The word ‘immersive’ earned such a significant amount of commercial value that it was used extensively in every ‘performance event in which the audience moved, or in which they were somehow surrounded or emplaced by the performance’ (Frieze 2016b, 1). In their books, both released in 2016, Adam Alston urges us to consider what lies ‘beyond’ immersive theatre, whereas James Frieze says that this genre needs to be ‘reframed’. The post-immersive manifesto was also published in 2020 by Ramos et al. in response to how capitalism has forced the once-alternative immersive theatre into the mainstream. The manifesto challenges participants and artists to reevaluate the principles of immersive experiences.

Immersive theatre and the study of it have both advanced significantly. Now, immersive theatre has been critically examined from a wide range of perspectives, including neoliberalism (Alston 2016a), experience economies (Biggin 2017; O’Hara 2017), environment-behavior studies (Gezgin and Imamoğlu 2023), democratisation (Wilson 2016), Indian aesthetic theory, rasa (Mitra 2016), and performer training (Middleton and Núñez 2018; Hogarth, Bramley, and Howson-Griffiths 2018). Artists have already experimented with immersive theatre in a variety of ways, such as addressing social issues, examining methods and processes, and exploring with mixed media and technology (See Tepperman and Cushman 2018; Estreet, Johnson, and Archibald 2021; Burns et al. 2022; Pearlman 2017; Hopkins and Netto 2018; Inthawat 2021; Chatchawan et al. 2022; Kearns 2020; Peterson 2020).

One of the trends in immersive theatre is the use of emerging technologies to add value to the individualised experience, attract more audience and enhance their engagement. Virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) have been adopted and integrated with immersive theatre from around 2016, led by the Royal National Theatre, UK, with a project called ‘Fabulous wonder.land’, and Punchdrunk with ‘Believe your Eyes.’ Being the first VR experience the National Theatre ever offered to its audience, ‘Fabulous wonder.land’ is based on Damon Albarn’s musical adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’, and was featured in the New Frontier section at the Sundance Film Festival 2016.Footnote 12 Subsequently, the National Theatre opened its Immersive Storytelling Studio, a space for artists to work with emerging technologies to develop dramatic storytelling and experiences. Some of the works produced here are ‘Draw Me Close’ (2017)’, ‘All Kinds of Limbo’ (2019), and ‘Museum of Austerity’ (2021).Footnote 13 Punchdrunk’s ‘Believe Your Eyes’, which was commissioned by Samsung, is a mixture of live-action VR film and physical performer interaction, and was critically acclaimed, receiving a Silver Lion in the Entertainment category at Cannes 2017.Footnote 14 The company has been working on new projects in collaboration with AR developer, Niantic since 2020.Footnote 15 A partnership between Piehole, a New York-based theatre company, and Tender Claws, a Los Angeles-based game development studio, also found success with an immersive experience that combines video games and live cabaret; ‘the Under Presents’ won VR Experience of the Year at the 4th International VR Awards in 2020.Footnote 16 Immersive theatre creators are now able to reach a wider audience and explore previously unimagined avenues for immersive storytelling thanks to immersive technologies. With the addition of digital technology, it appears that the definition of immersive theatre has become even broader. The emphasis on the physical space, in which the audience had the ability to freely navigate, has shifted. Attendees of immersive theatre can now engage with virtual surroundings, albeit with limited mobility (like in a VR experience). While the continuous evolution of immersive theatre is commendable, the arguments put forth by White and Carlson still persist. The term ‘immersive’ continues to be used in a way that lacks definition, and this trend is further escalating. Therefore, it is essential to establish a more precise and comprehensive characterisation of immersion, otherwise, it is likely to quickly lose its significance and could become only a passing fad.

Immersive technologies and theatre

As we noted earlier in this article, there is a stark difference between the experiences and expectations that arise from immersive events in theatre and non-theatre contexts. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the use of immersive technology within the realm of theatre (in contrast to immersive theatre) can be traced back to the latter part of the twentieth century, and the concept of immersion served as the common thread that connected theatre and VR. Broadly referring to ‘the sum of the hardware and software systems that seek to perfect an all-inclusive, immersive, sensory illusion of being present in another environment’ (Biocca and Delaney 1995, 63), VR dates back to the 1960s with Ivan Sutherland’s development of the first head-mounted display, while its significant developments took place in the 1980s (Dixon 2006; Mütterlein 2018). Since the inception of VR, the goal of computer graphic designers has always been to fully immerse users in virtual environments. Mark Reaney, Director of the Institute for the Exploration of Virtual Realities (i.e.VR) at the University of Kansas, asserts that it is the concept of immersion that unites the art of theatre and VR, ‘making VR a powerful new tool in scenography. Conversely, theatrical practices may prove to be worthy of emulation in designing virtual environments’ (1999, 183). At first, the replication of real-world settings and situations was the ultimate goal of most VR applications, for example, training pilots and surgeons, designing new architecture and prototyping new machines. The scenario is reversed in conventional theatre, where the audience is expected to be so immersed in the fictional world being portrayed that they ignore the physical environment of the theatre (for example, the proscenium arch, lighting equipment, and fellow audience members). In his 2006 journal article, Steve Dixon gives an overview of the history of VR in performance, with examples drawn from i.e.VR, the Art and Virtual Environment Project conducted at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, which provided selected artists with a team of engineers, assistants, and access to the most advanced studios and equipment at the time (1991–1994), and a collaboration between Blast Theory and the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham. He draws the conclusion that there had only been a small number of (yet spectacular) VR performances, and that there had been little interest in fusing the technology with performance because of how expensive and time-consuming it would be to create and execute.

As VR technology has become cheaper, more user-friendly, and more intuitive over time, the scenario has altered. Millions of people use it globally, and the VR experience that was once intended for solitary usage has evolved into a group activity that involves interaction. Additionally, the COVID-19 epidemic and the closing of theatres and performance spaces forced artists to look into other avenues for the creation and presentation of their work. For instance, in 2021, the Royal Shakespeare Company produced a virtual reality production, ‘Dream’, based on William Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ which more than 20,000 people saw and engaged in over the course of three days. The audience was able to see the seven actors’ avatars on screen, and special effects were even added to some parts as it was performed live in a studio utilising motion capture technology. Although it was seen as a work-in-progress, it expanded the scope of what theatre may be and what it can do, as well as its opportunities for audience outreach (Akbar 2021). Focusing on live theatre and performance that is delivered in VR, or VR theatre, Reis, Ashmore (2022) consider it a highly interactive and playful art form that goes beyond traditional immersive theatre by offering a sensorially rich and aesthetically captivating experience similar to a lucid dream. Participants become avatars, fully immersing themselves in the theatrical world, and blurring the line between audience and performer. ‘[E]very person engages in lively and meaningful interactions triggered by a given dramaturgical construct. This reveals its essence as a truly ritualistic integrative practice, far away from the mere communication mediated by technology’ (23).

By revisiting previous hybrid VR/theatre forms, we can discern fundamental ideas that contribute to the immersive experience. The concepts under discussion are referred to as ‘liveness’ and ‘the experience of being transferred to another domain or assuming a different persona.’ The fundamental aspect of the theatrical event is in its inherent live nature, which is further augmented through the utilisation of virtual reality (VR) technology to create the illusion of immersing oneself in an alternative environment or assuming an alternate identity. Can the mentioned features of both types of media provide us with a comprehensive understanding of immersion in diverse contexts?

The development of immersive communication

In the context of communication, the word ‘immersive’ refers to a concept and an experience quite different from those in theatre. In contrast to immersive theatre, the definitions of ‘immersive communication’ are usually clear and straightforward. Dubbed as ‘the communication paradigm of the third media age’ (Li 2020),Footnote 17 immersive communication ‘allows users to have lifelike experiences in the physical world, the virtual world, or both, with interactions via 3D audiovisual and/or haptic information exchange’ (Shen et al. 2023, 5). The users can exchange ‘natural social signs with remote people, as in face-to-face meetings, and/or experiencing remote locations (and having the people there experience you) in ways that suspend disbelief in being there. There is transparency, fluidity of interaction, a sense of presence’ (Apostolopoulos et al. 2012, 975). Immersive communications are still considered ‘emerging’, and they are expected to have a significant impact on all aspects of our lives in the future.

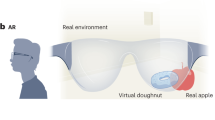

VR, mentioned earlier, is a component of immersive communications that has been developing at a faster pace that other technologies. Similarly, augmented reality (AR), which is a technology that integrates digital information with the user’s physical environment in real time, began its development in the 1960s. In the early years, the goal of utilizing AR was to help users ‘perform the task at hand with less effort’ (Orlosky, Kiyokawa, and Takemura 2017, 133–134), such as when scientists at the Boeing Corporation developed an AR system to help workers put together wiring harnesses (Orlosky, Kiyokawa, and Takemura 2017; Bottani and Vignali 2019), and when it was used for image-guided surgery (Syed et al. 2023). However, since the late 1990s, augmented reality (AR) applications have been developed in a variety of industries for a variety of purposes. This has been made possible by the development of camera systems that can analyse the physical environment in real time, by freely available software toolkits, such as the ARToolKit, and by the widespread use of hardware devices (primarily smartphones and tablets) capable of supporting AR applications. AR gained widespread public acceptance in the late 2000s through the entertainment sector, with the help of games like Sony’s Eyes of Judgement, which is regarded to be the first AR game, and Nintendo’s Pokemon GO, the most popular AR game to date (Orlosky, Kiyokawa, and Takemura 2017). Nee et al. (2012) asserts that new AR applications are being created nearly every day, and that AR technology has outperformed VR, due to its capacity to deliver high user intuition and relative simplicity of implementation.

VR, AR, and Mixed Reality (MR), which is a combination of VR and AR that fuses the physical and digital worlds to create new environments where physical and digital items co-exist and interact,Footnote 18 are technologies under the umbrella of Extended Reality (XR). XR creates artificial scenery from either the real world or the virtual world by fusing sensory input with virtual settings. Users can engage with virtual avatars and access XR content by wearing headsets or portable display devices. XR and other technologies, such as haptic communication and holographic communication, are part of the much larger field of immersive communications, with a myriad of technologies, platforms, and products being developed to fulfil the potential of immersive communications and revolutionise media functions, as well as how people interact, work, and entertain (Shen et al. 2023).

Immersive communication offers new perspectives on space, time, and the participants, which may alter our understanding of an immersive experience. According to Qin Li (2020, 56-62), the past, present, and future are all integrated, there is no distinction between virtual and physical space, and a person can live in both worlds simultaneously, make their own choices, and move freely between the two at any time. Moreover, the lines that once divided work, play, and life are disappearing. Work and play are meant to be interwoven and indistinguishable. Therefore, it may be argued that in the context of immersive communication, a sense of immersion is associated with the disappearance of boundaries and subsequent freedom to move between or exist simultaneously in two or more environments.

The concept of immersion in immersive theatre

Since the inception of immersive theatre, scholars have debated the concept of immersion and the viability of so-called ‘immersive’ performances. Gareth White (2012), for example, goes into great detail about the concept, drawing from his own experiences in immersive performances as well as Heidegger’s philosophy of art. He concludes that although the word immersion suggests some kind of access to the inside of the piece, the audience-participants are never inside it, and the phrase immersive maintains a subject-object distinction. Later on, Machon (2013) clarifies the concept of immersion and highlights three categories that can be used to describe it within the immersive theatre experience, drawing on Gordon Calleja’s study on the concept of immersion in Gaming Theory and Game Studies;Footnote 19 they are 1) immersion as absorption 2) immersion as transportation 3) total immersion.

The first category includes immersive theatrical experiences that fully engage audience-participants in terms of concentration, imagination, and interest, while the second one involves the audience being imaginatively relocated to a different setting, coexisting and interacting with other human bodies (i.e. performers and other participants). These two categories of immersion resonate with Klich, Scheer (2012)’s two types of immersion: ‘cognitive’, which represents the mental engagement with an imagined reality, and ‘sensory’, which is an embodied experience in a real setting. For Machon, no matter the scale of the immersive event, both types of immersion can be established. When the first and second categories are combined the third category, total immersion, is achieved.Footnote 20 This is when the audience-participants are able to create their own journey and recognise their own ‘praesence’ (Machon 2016b, a, 2013) within it. Machon (2016b, 40) elaborates on the use of the term as follows:

Here ‘presence’ directly correlates to its etymological roots, from praesens, ‘to be before the senses’ (prae, ‘before’; sensus, ‘feeling, sense’). In immersive theatre, this attention to the senses is acutely and haptically perceived rather than a dormant feature of spectatorial engagement. The spectator is aware of the involvement of the senses and this heightened awareness is often central to the immediate experience and any subsequent analytical interpretations. […] Activating the imagination and proprioceptive senses in such ways enables interactors to intuit their way through the event.

As more and more theatrical performances have utilised the term ‘immersive’ to draw audiences, it has become less clear what the experience of immersion is for the audience-participants. Jarvis (2019), argues that ‘immersion’ has no single definition and must be defined in light of the context being examined, and that in most immersive performances, the audience is never transported into the dramatic world, ‘instead their presence is doubled; they occupy both real and dramatic or virtual spaces as participant-character’ (91). In the book Immersive Embodiment: Theatres of Mislocalized Sensation (2019), Jarvis argues that the use of the term ‘immersive’ and the definitions of ‘immersion’ by theatre scholars, such as Machon and Biggin, are both problematic and inadequate. He supports White’s assertion that many immersive performances are unable to reach the state of immersion they aim to achieve. Drawing on examples from a wider cross-disciplinary field, Jarvis proposes a concept of immersion that ‘places the participants in a position outside of their habitual bodily experience and within virtualized subjects without separation’ (81). This experience of ‘crossing the boundary of one’s own skin and becoming […] the other body via an illusionistic transaction [… or] body transfer illusion’ (91–92) is achieved in what he terms ‘theatres of mislocalised sensation’ (2019), which could only occur with the use of immersive technologies, such as VR. The previously discussed uses of VR in theatre, which started in the late twentieth century, are consistent with this idea of immersion, which also aligns with Qin Li (2020, 45)’s assertion that the ultimate goal of immersive technology is ‘to let people immerse themselves inside this new, enhanced world while not feeling or being able to tell the difference between physical objects and virtual objects; the visually enhanced information becomes part of the physical information and finally makes the virtual become real.’

The employment of technology, especially immersive (communication) technologies, in performance is considered a necessary component of Jarvis’ concept of immersion. A theatrical production cannot be considered immersive without it. Thus, he only challenges the term’s application to site-specific events where participants are free to move around the space and engage their senses with actual objects and architectural details. Earlier works by Punchdrunk and other companies influenced by them (including Thailand’s FULLFAT Theatre) are examples of such events. It is important to note that Punchdrunk’s Artistic Director does not refer to his own works as ‘immersive’, because the focus is entirely on the physical environment (Biggin 2017, 177).

A conceptual framework for cross-disciplinary immersive theatre and experiences

Jarvis’ concept of immersion offers a basis for discerning between events that present an immersive phenomenon and those that are limited to site-specific experiences. The scope of our inquiry extends to the development of a comprehensive framework aimed at facilitating the creation of immersive experiences across varied situations. Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge (2023) present a comprehensive framework for immersive experience which includes four elements (facilitators) that combine to create an immersive experience: systems, spatial, social/empathic, and narrative/sequential. They are defined as follow (8):

-

1.

System immersion: physical and mental engagement in mechanics and activity of the experience

-

2.

Spatial immersion: transportation into a different environment creating a sense of presence in the new environment

-

3.

Social/empathic immersion: emotional connection with actors in the experience and relatedness to user’s social context

-

4.

Narrative/sequential immersion: compulsion to continue the progression of the storyline or sequence of events in the experience

Each of the facilitators are complete with a set of design guidelines for a successful creation of immersive experiences.Footnote 21 This framework emerged from a thorough qualitative study that employed the Delphi method,Footnote 22 which involved several rounds of questioning during which specialists in various contexts expressed their views on the design of immersive experiences (See Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge 2023). It can be presumed that theatre is included in their study under the heading of ‘games and entertainment,’ even though perspectives from the immersive theatre industry are not included. However, because the framework centres on the use of immersive technologies, certain types of so-called immersive theatre that emphasise site-specificity and physical settings are not relevant.

This article then proposes a revised framework (Fig. 1) that incorporates the concepts of immersion put forward by both Machon and Jarvis. In addition to the four facilitators, ‘bodily immersion’ is an essential component that brings the immersive experience to an effective end. While systems immersion entails ‘physical and mental engagement’ and spatial immersion involves ‘creating a sense of presence in the new environment’, there is no suggestion of ‘bodily transference’ as emphasised by Jarvis (2019). Referring to Machon’s categories of immersion, the framework by Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge could represent only the first two types: immersion as absorption (systems, social/empathic, narrative/sequential) and immersion as transportation (spatial). The inclusion of bodily immersion could lead not only to a sense of presence, but the state of praesence, a lived experience of the ‘physical body responding within an imaginative, sensual environment’ (Machon 2013, 61). The activation of proprioceptive senses as well as imagination establishes the audience-participant’s praesence, generating total immersion, and enables them to ‘intuit their way through the event’ (Machon 2016b, 40). Thus, the fifth facilitator can be defined as:

-

5.

Bodily immersion: sensation of bodily transference, generating illusory ownership over virtual bodies and activating praesence

According to Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge (2023), systems immersion can be activated by creating a sense of influence, establishing clarity of purpose and tasks, as well as increasing complexity of the activities, while spatial immersion is stimulated by creating coherency within the environment which can be explored, and ensuring smoothness in the interactivity. Social and empathic immersion is facilitated by providing insight into the background of individuals in the experience as well as meaningful interactions. Empathic immersion can also be triggered when there is high relatability between the individuals and other participants. For narrative/sequential immersion, involvement of the participants with the development of a storyline that contains a narrative arc and an unexpected but logical sequence of events is crucial. To illustrate how these aspects are supported, examples from the worlds of video games, museums, and theme parks are provided. For instance, in a theme park attraction, visitors might be assigned an active role as a specific character within a story (narrative/sequential immersion); they might also be required to work in groups (social/empathic immersion) and navigate an intricate set full of artifacts (spatial immersion) using a game controller (systems immersion) (4).

Supporting Jarvis’s and Machon’s notions of immersion, and incorporating Li’s theory of immersive communication and the features of earlier hybrid VR/theatre forms discussed previously, this article proposes that in order for bodily immersion to be activated, the participant’s imagination and proprioceptive senses must be engaged. Not only that, a sense of becoming the other body must be created. In the present time and with the currently available technologies, this transformative act is generated using VR technology, and can be referred to as ‘VR body illusion’ (Jarvis 2019, 128). An immersive experience is a result of the interaction between all five facilitators, and the addition of bodily immersion also enhances this interaction, as it is strongly associated with empathy (Jarvis 2019). Moreover, praesence, or a heightened awareness of the involvement of the senses in the lived moment that enables participants to navigate the situation using their intuition, is engendered and maintained through the careful consideration of the systems, space, and narrative. In the realm of theatre, examples of an immersive experience consisting of all five elements are: Punchdrunk’s ‘Believe Your Eyes’ (2006–2007), featuring a live cast of four actors, a 360-degree film timed to the performance, and an immersive environment with sensory special effects and dramatic sound design,Footnote 23 Jane Gauntlett’s ‘In My Shoes’ (2017), a series of Interactive, documentary-style performances that put the audience in the centre of the action and guided them through the challenges of being human,Footnote 24 and Layered Reality’s ‘the Gunpowder Plot’ (2022–2023), which combined live performers, digital technologies (VR, projection mapping, and holograms), scenic designs and special effects that engage participants’ physical sensations.Footnote 25

The argument presented in this paper asserts that the integration of VR technology is highly significant in enabling a complete sense of immersion. We recognise that this viewpoint significantly limits the concept of immersive experience; yet, we maintain that a more focused and limited scope is essential. Although the inclusion of the fifth facilitator as an essential part of the framework for the creation of an immersive experience may imply that many self-defined ‘immersive’ experiences cannot offer the true sense of immersion that they strive for (such as the examples in Thailand mentioned at the beginning of this article, some of the performances that were marketed as immersive at the beginning of the twenty-first century in Europe and America, as well as some that are being performed today all over the world without the use of immersive technologies, particularly VR or MR), it is not our intention to disregard their value and potential.

Instead, by looking back at the history of immersive theatre, as well as the development of immersive technologies and how they have been increasingly used in the theatre field, we acknowledge the contributions, experiments, and efforts that have helped us along the route to immersion. It is evident that performance creators as well as practitioners in other fields are getting closer to realising the full potential of immersion, which goes beyond simply enhancing our enjoyment of entertainment, and holds great potential for our society in a number of areas, including education, healthcare, culture, tourism, and overall human advancement.

Conclusion

By integrating the viewpoints on immersion offered by Jarvis (2019) Machon (2016b, 2013), and Li (2020) with the framework by Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge (2023), this paper proposes a revised conceptual framework for the creation of an immersive experience across many contexts, with a particular focus on the domain of theatre, where a precise definition of immersion has yet to be established. The fifth element added is ‘bodily immersion,’ which is defined by the experience of bodily transference, creating illusory ownership over virtual bodies, and activating praesence, can be activated by the use of immersive technologies, particularly VR. This article traces the evolution of immersive theatre and immersive technologies as a continuation of the path to realising the fullest potential of immersion. Our society is getting closer to achieving that, owing to current trends in immersive experiences that incorporate theatre and immersive technologies. Increased possibilities are seen, not only in the entertainment domain, but across a variety of fields, that collectively open a new chapter in human communication. These represent what Qin Li (2020) describes as ‘a profound media revolution’ (158) that integrates the virtual world and the physical world. It ‘extends, in an all-around way, humans’ vision, hearing, touch, and smell. It is not only an indispensable tool for people’s wisdom but is also bound to boost the transformation of human beings into biological media’ (158).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

‘Unless.’ Bangkok 1899, 8 December 2019. https://bangkok1899.org/Unless.

Supateerawanitt, Arpiwach. ‘Fullfat Theatre Speaks out on Breaking Theater Traditions and Highlighting the Importance of Art.’ Time Out Bangkok, 24 June 2021. https://www.timeout.com/bangkok/fullfat-theatre-interview.

Mind Da Hed. ‘Siam Supernatural Tour.’ a day magazine, 14 February 2021. https://adaymagazine.com/siam-supernatural-tour-fullfat-theatre-eyedropper-fill/.

‘2046 the Greater Exodus.’ STUDIO11206. Accessed 4 July 2023. https://www.studio11206.com/work/2046.

‘Hanuman Su Su! New Performance That Unleashes the Imagination.’ www.thairath.co.th, 30 August 2022. https://www.thairath.co.th/lifestyle/life/2486390.

‘Nowhereland.: The Eden.’ Bangkok Art & Culture Centre. Accessed 4 July 2023. https://en.bacc.or.th/event/3010.html.

Chamwutpreecha, Punyaporn. ‘Behind the Scene of ‘LUNA: The Immersive Musical Experience.” Mappa Learning, December 7, 2022. https://mappalearning.co/luna-the-immersive-musical-experience/.

‘The End Is Coming, Immersive Exhibition.’ Eventpop. Accessed 4 July 2023. https://www.eventpop.me/e/14075/theendiscoming.

‘Walk through Van Gogh Alive Bangkok, an immersive exhibition and pay homage to the great painter.’ www.thairath.co.th, April 6, 2023. https://www.thairath.co.th/lifestyle/life/2671318.

Sereemongkonpol, Pornchai. ‘True Digital Park Unveils Immersive Art Show in Three Phases.’ https://www.bangkokpost.com, 21 December 2022. https://www.bangkokpost.com/life/arts-and-entertainment/2465814/true-digital-park-unveils-immersive-art-show-in-three-phases.

More recently, Punchdrunk has been exploring interactive audience experiences not only within physical environments, but also inside virtual reality, television, and digital gaming (Punchdrunk. ‘Work.’ Punchdrunk. Accessed 21 October 2023. https://www.punchdrunk.com/work/)

‘Fabulous Wonder.Land VR.’ 59 Productions, 17 November 2020. https://59productions.co.uk/project/fabulous-wonder-land-vr/.

‘Immersive Storytelling Studio: National Theatre.’ Immersive Storytelling Studio, National Theatre. Accessed July 4, 2023. https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/about-us/theatre-makers/immersive/.

Punchdrunk. ‘Believe Your Eyes.’ Punchdrunk. Accessed 5 July 2023. https://www.punchdrunk.com/project/believe-your-eyes/.

‘Pokémon Go Creator Joins Punchdrunk Theatre for Interactive Venture.’ The Guardian, 30 June 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/jun/30/pokemon-go-game-creator-niantic-joins-punchdrunk-theatre-interactive-venture.

Stevens, Amelia. ‘How VR and AR Are Changing the World of Immersive Theater.’ AMT Lab @ CMU, 16 August 2022. https://amt-lab.org/blog/2021/8/how-vr-and-ar-are-changing-the-world-of-immersive-theater.

Li (2020) describes the first media age as one-way, one-on-one communication, like a distribution of leaflets in a lobby of a building. The second media age is represented by elevator advertising, presented using graphic media resources. Advertising in a closed environment, like an elevator, provides an advantage of focus attention. In the third media age, the communication range is widened by its extensive interconnectedness, enabling it to reach everyone, everywhere, at any time.

See Rokhsaritalemi, Sadeghi-Niaraki, and Choi 2020 for a review on MR

Calleja, Gordon. 2011. In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation. London and Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

‘Total immersion’ is also considered the highest level of immersion in gaming experiences for Brown and Cairns (2004).

See Han, Melissen, and Haggis-Burridge 2023, 8 for a full list of design criteria

The Delphi technique is a widely used method for gathering information from experts in a specific field. It involves a group communication process aimed at achieving consensus on a real-life issue. This technique is commonly applied in various areas such as program planning, needs assessment, policy determination, and resource utilization. Its goal is to generate diverse options, uncover underlying assumptions, and align judgments across different disciplines.

Harkness, Hector. ‘Believe Your Eyes.’ Accessed 27 October 2023. https://www.hectorharkness.com/believe-your-eyes/.

Gauntlett, Jane. ‘The In My Shoes Project.’ Accessed 27 October 2023. http://janegauntlett.com/inmyshoesproject.

‘The Gunpowder Plot’ Accessed 27 October 2023. https://gunpowderimmersive.com/.

References

Akbar A (2021) The RSC’s hi-tech dream opens up a world of theatrical possibility. The Guardian, 17 March 2021, Stage. Accessed 29 June 2023 https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2021/mar/17/rsc-a-midsummer-nights-dream

Alston A (2013) Audience participation and neoliberal value: risk, agency and responsibility in immersive theatre. Perform Res 18(2):128–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2013.807177

Alston A (2016a) Beyond immersive theatre: aesthetics, politics and productive participation. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Alston A (2016b) Making mistakes in immersive theatre: spectatorship and errant immersion. J Contemp Drama Engl 4(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcde-2016-0006

Apostolopoulos JG, Chou PA, Culbertson B, Kalker T, Trott MD, Wee S (2012) The road to immersive communication. Proceedings of IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2011.2182069

Artaud A (1958) The theatre and its double. Translated by Mary Caroline Richards. Grove Press, New York

Berkman MI, Akan E (2019) Presence and immersion in virtual reality. In: Encyclopedia of Computer Graphics and Games, edited by Newton Lee. Springer, Cham

Biggin R (2014) Audience immersion: environment, interactivity, narrative in the work of Punchdrunk. PhD in Drama, Drama, University of Exeter

Biggin R (2017) Immersive theatre and audience experience: space, game and story in the work of punchdrunk. Springer, Cham

Biggin R (2020) Labours of seduction in immersive theatre and interactive performance. N. Theatre Q 36(1):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266464X20000111

Biocca F, Delaney B (1995) Immersive virtual reality technology. In Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, edited by Frank Biocca and Mark R. Levy. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, p 57-124

Bottani E, Vignali G (2019) Augmented reality technology in the manufacturing industry: a review of the last decade. IIE Trans 51(3):284–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/24725854.2018.1493244

Brown E, Cairns P (2004) A Grounded investigation of game immersion. Proceedings of ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2004

Burns PA, Klukas E, Sims-Gomillia C, Omondi A, Bender M, Poteat T (2022) As much as i can – utilizing immersive theatre to reduce hiv-related stigma and discrimination toward black sexual minority men. Community Health Equity Research & Policy:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X221115920

Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary & Thesaurus (2023) Immerse. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/immerse

Carlson M (2012) Immersive theatre and the reception process. Forum Modernes Theater 27(1-2):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1353/fmt.2012.0002

Chatchawan C, Wonghakeaw P, Suriyadong S, Kittikong T (2022) LOOP: the creation of immersive theatre on whodunit. Burapha Arts. Journal 25(1):9–32

Dixon S (2006) A history of virtual reality in performance. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.1386/padm.2.1.23/1

Estreet AT, Johnson N, Archibald P (2021) Teaching social justice through critical reflection: using immersive theatre to address hiv among black gay men. J Soc Work Educ 59(1):243–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1969303

Frieze J (2016a) Reframing immersive theatre: the politics and pragmatics of participatory performance. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Frieze J (2016b) Reframing immersive theatre: the politics and pragmatics of participatory performance. In: Reframing immersive theatre: the politics and pragmatics of participatory performance, edited by James Frieze. Palgrave Macmillan, London, p. 1-25

Gezgin Ö, Imamoğlu Ç (2023) Audience behavior in immersive theatre: an environment-behavior studies analysis of Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More. Studies in Theatre and Performance. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2023.2185928

Han DD, Melissen F, Haggis-Burridge M (2023) Immersive experience framework: a delphi approach. Behaviour & Information Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2183054

Hogarth S, Bramley E, Howson-Griffiths T (2018) Immersive worlds: an exploration into how performers facilitate the three worlds in immersive performance. Theatre, Dance Perform Train 9(2):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2018.1450780

Hopkins M, Netto C (2018) Gargantuan: the thrills and challenges of creating immersive theatre. Can Theatre Rev 173:53–58. https://doi.org/10.3138/ctr.173.009

Inthawat P (2021) Directing process of narit pachoei’s chao khao yoo in a form of a site-specific immersive theatre on an online space. Master of Arts in Dramatic Arts, Department of Dramatic Arts, Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University

Jarvis L (2019) Immersive embodiment: theatres of mislocalized sensation. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Kearns RM (2020) Nostrovia: methods in creating immersive theatre for audiences. Masters of Fine Arts Master’s Degree Thesis, Graduate Program in Dance, York University

Kerrison M (2022) Immersive storytelling for real and imagined worlds: a writer’s guide. Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City

Klich R, Scheer E (2012) Multimedia performance. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Li Q (2020) Immersive communication: the communication paradigm of the third media age. Routledge, Abingdon

Machon J (2009) (Syn)aesthetics: redefining visceral performance. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Machon J (2013) Immersive theatres: intimacy and immediacy in contemporary performance. Palgrave. Macmillan, New York

Machon J (2016a) On being immersed: the pleasure of being: washing, feeding, holding. In: Reframing immersive theatre: the politics and pragmatics of participatory performance, edited by James Frieze, 29-42. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Machon J (2016b) Watching, attending, sense-making: spectatorship in immersive theatres. J Contemp Drama Engl 4(1):34–48. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcde-2016-0004

Middleton D, Núñez N (2018) Immersive awareness. Theatre, Dance Perform Train 9(2):217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2018.1462252

Mitra R (2016) Decolonizing immersion: translation, spectatorship, rasa theory and contemporary British dance. Perform Res 21(5):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2016.1215399

Mütterlein J (2018) The three pillars of virtual reality?: investigating the roles of immersion, presence, and interactivity. Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, Hawaii, USA

Nee AYC, Ong SK, Chryssolouris G, Mourtzis D (2012) Augmented reality applications in design and manufacturing. CIRP Ann 61(2):657–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2012.05.010

Nelson R, Vanhoutte K, Barton B, Fewster R, Wynants N (2010) Node: modes of experience. In: Mapping Intermediality in Performance, edited by Robin Nelson, Sarah Bay-Cheng, Chiel Kattenbelt and Andy Lavender, 45-48. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

O’Hara M (2017) Experience economies: immersion, disposability, and Punchdrunk Theatre. Contemp Theatre Rev 27(4):481–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10486801.2017.1365289

Orlosky J, Kiyokawa K, Takemura H (2017) Virtual and augmented reality on the 5g highway. J Inf Process 25:133–141. https://doi.org/10.2197/ipsjjip.25.133

Pearlman E (2017) Brain opera: exploring surveillance in 360-degree immersive theatre. PAJ: A J Perform Art 39(2):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1162/PAJJ_a_00367

Peterson AC (2020) Reconsidering liveness: interactivity and presence in hybrid virtual reality theatre. Graduate Program in Theatre Master’s Degree Thesis, Theatre, The Ohio State University – Columbus

Ramos JL, Dunne-Howrie J, Maravala PJ, Simon B (2020) The post-immersive manifesto. Int J Perform Arts Digital Media 16(2):196–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794713.2020.1766282

Reaney M (1999) Virtual reality and the theatre: immersion in virtual worlds. Digital Creativity 10(3):183–188. https://doi.org/10.1076/digc.10.3.183.3244

Reis AB, Ashmore M (2022) From video streaming to virtual reality worlds: an academic, reflective, and creative study on live theatre and performance in the metaverse. Int J Perform Arts Digital Media 18(1):7–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794713.2021.2024398

Shen X, Gao J, Li M, Zhou C, Hu S, He M, Zhuang W (2023) Toward immersive communications in 6G. Front Computer Sci 4:2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2022.1068478

Slater M, Lotto B, Arnold MM, Sanchez-Vives MV (2009) How we experience immersive virtual environments: the concept of presence and its measurement. Anuario de Psicolía 40(2):193–210

Syed TA, Siddiqui MS, Abdullah HB, Jan S, Namoun A, Alzahrani A, Nadeem A, Alkhodre AB (2023) In-depth review of augmented reality: tracking technologies, development tools, ar displays, collaborative ar, and security concerns. Sensors 23(1):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23010146

Tepperman J, Cushman M (2018) BRANTWOOD: canada’s largest experiment in immersive theatre. Can Theatre Rev 173:9–14. https://doi.org/10.3138/ctr.173.002

Turner R, Kasperczyk H (2022) Space for the unexpected: serendipity in immersive theatre. In: The art of serendipity, edited by Wendy Ross and Samantha Copeland, 101-125. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Warren J (2017) Creating worlds: how to make immersive theatre. Nick Hern Books, London

White G (2012) On Immersive Theatre. Theatre Res Int 37(3):221–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883312000880

Wilson A (2016) Punchdrunk, participation and the political: democratisation within Masque of the Red Death? Stud Theatre Perform 36(2):159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2016.1157748

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Punpeng, G., Yodnane, P. The route to immersion: a conceptual framework for cross-disciplinary immersive theatre and experiences. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 961 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02485-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02485-1