Abstract

COVID-19 has transformed customer behavior, notably in FMCG retailers. Although online stores grow, retail mix instruments remain essential for traditional shops, as these affect customer value perceptions and engagement. While previous studies suggest that customer value perceptions and engagement are linked, little is known about the effects of retail mix instruments on customer value perceptions and engagement. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap. In this study, the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework was used to propose the a priori conceptual framework, which was further employed in investigating the phenomena and the three concepts: the impact of retail mix instruments (S) on consumer value perceptions (O) and customer engagement (R). Interviews were conducted with 40 informants recruited by convenience sampling and snowballing techniques. They were Gen-X and Gen-Y and had experience visiting two FMCG retailers in Thailand. A thematic analysis was undertaken to analyze the obtained data. The a priori conceptual framework had been revised iteratively according to the emerging theme, resulting in a new conceptual framework containing descriptive details in terms of significant themes identified from the field data and potential relationships among the three concepts. Findings revealed 12 retail mix instruments and the effect of COVID-19, which were found to affect six types of customer value perceptions, resulting in four customer engagement behaviors. The proposed conceptual framework, the study’s primary theoretical contribution of the study, is used to guide potential future research agenda. To suggest how FMCG retailers may leverage the proposed conceptual framework to design strategies to promote customer engagement behaviors, an application of sales promotions is illustrated and suggests how to use sales promotion activities to induce customer value perception and their engagements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, online stores became popular because consumers perceived online shopping as safer than visiting a physical store (Verhoef et al. 2023). In the aftermath, a recent market survey found that consumers preferred to return to physical retail stores for many reasons (e.g., seeing products and feeling the social aspect of shopping); however, they perceived a less enjoyable experience (Theatro 2023). Additionally, the current slowing economy, inflation, and decreased consumer spending influence the retail industry (Deloitte 2023). These highlight the importance of brick-and-mortar stores and fierce competition in the following standard era.

In the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industry, retailers also faced a high competition level not only before the pandemic (Mittal and Jhamb 2016) but also in the aftermath period (McKinsey 2022) and their everyday challenges involve maintaining patronage and sales rates (Wang et al. 2020). Customers have more choices when shopping, and customers may not be keen to shop from FMCG retailers who engage them intensely if no unique value proposition is offered (Javornik and Mandelli 2012; Mittal and Jhamb 2016). How can FMCG retailers sustain these upcoming trends? One classical practice is developing a business strategy that delivers customer value and satisfaction, including customer engagement (Javornik and Mandelli 2012; Sweeney and Soutar 2001). Research suggests that value proposition is essential to a physical retail store (Javornik and Mandelli 2012) because retail customers are value-driven (Levy 1999); thus, they always work to establish customer value through the retail marketing mix (Blut et al. 2018; Moore 2005), and the retail mix is an instrument used to influence customer behavior (Chen and Tsou 2012), create customer experiences (Rintamäki and Kirves 2017), and increase customer engagement (Blut et al. 2018; Pansari and Kumar 2017).

All the foregoing prompted us to conduct a literature review on the retail marketing mix, customer value, and customer behavior. It was found that previous studies investigated the effects of retail mix instruments on customer engagement (Blut et al. 2018; Moore 2005) and on customer value perceptions (O’Cass and Grace 2008), including the effects of customer value perceptions on customer engagement (Wongkitrungrueng and Assarut 2020). The review results did not identify the interrelationships between these concepts. Understanding the customer decision-making process is more critical than focusing on the ultimate purchase decision (Hunt 2014). According to the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework (Mehrabian and Russell 1974), this study proposes that retail mix instruments (stimuli) can activate customer value perceptions (cognitive mechanisms), which results in customer engagement (responses). In other words, customer value perceptions may play a mediating role between retail mix instruments and customer engagement. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the potential relationships between retail mix instruments, customer value perceptions, and customer engagement.

However, there are some key challenges when exploring these three constructs. First, there are various retail mix instruments (Blut et al. 2018; Paul et al. 2016), and different retail contexts have different sets of retail mix instruments. Customer value perceptions are also multi-dimensional, as customer experience involves more than one value aspect (Zeithaml et al. 2020); thus, a single retail mix instrument may result in many customer value perceptions. Different value perceptions may result in various aspects of customer engagement, which can be approached from diverse perspectives (Yu et al. 2022).

This study will fill the gaps in retail literature by exploring the customer decision-making process regarding the potential effects of retail mix instruments on customer value perceptions and engagement. However, the scope is narrowed down to only the FMCG context. Specifically, the main research question is to explore the effects of retail mix instruments that are attractive to FMCG’s customers and can influence their value perceptions and engagements. Employing a qualitative approach led us to generate rich data that explains the complex phenomena involving these three constructs. A conceptual framework, the paper’s primary contribution, is then proposed. To provide an application of the proposed framework, the authors revisited the field data and presented a case of sales promotion (one of many retail mix instruments) as an example of marketing practice, which may hint at ideas for retailers to design a compelling retail mix to suit the customers’ behavior and decision process (Hanaysha et al. 2021).

The following section introduces the S-O-R framework, which is employed as an overarching theoretical foundation of this study and presents a review of literature on the FMCG retail context concerning retail mix instruments, dimensions of customer value, and customer engagement. Then, the research methodology used in the study is presented and followed by findings, which are synthesized to develop and propose a conceptual framework, research propositions, and recommendations for future studies. Practical discussions that may benefit marketing practice are also suggested. The last section summarizes the study’s contributions and limitations.

Literature review

The stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework

The S-O-R framework is a behavioralist theory developed to understand human behavior concerning external factors (Mehrabian and Russell 1974). The framework consists of stimuli in the environment (S) that affect the organism (O), or more specifically, consumers’ emotions and cognitive mechanisms, which result in the behavioral responses (R). In the retail context, the S-O-R framework has long been applied to various situations, such as the shopping field (Robert and John 1982), online shopping (Eroglu et al. 2001), luxury retails (Cheah et al. 2020), and shopping during the pandemic (Laato et al. 2020).

In the context of this study, stimuli are retail mix instruments that customers interact with when they visit physical stores. The organism aspect of S-O-R should be customer value perceptions because retail mix instruments can influence customers’ cognitive and affective mechanisms (Liu-Thompkins et al. 2022). Once customers have a certain level of magnitude of perceptions, they should show some behavioral responses such as intention (Laato et al. 2020), engagement (Chen and Tsou 2012), and loyalty (Terblanche 2017).

Retail mix instruments used in the FMCG context as retail’s stimuli (S)

Various retail mix instruments are reported in the retail literature, and different sets of retail mix instruments are suitable for use in different retail contexts. Mittal and Jhamb (2016) provided a set of retail mix instruments (e.g., an assortment of merchandise, improved quality, and proper display) that could be used in a shopping mall. For the context of three retail stores (supermarket, clothing, health, beauty, and lifestyle store), Terblanche (2017) proposed the 6Ps of a retailer’s products, promotion efforts, personnel, presentation, place, and price. Aparna et al. (2018) suggested retail mix instruments used in six retail stores context (department stores, hypermarkets, supermarkets, specialty stores, discount stores, and convenience stores): assortment, price, transactional convenience, and experience.

According to Blut et al. (2018), they concluded seven sets of common-used retail mix instruments, namely, product (product range and quality of products), service (customer service, maneuverability, orientation, parking, retail tenant mix, service tenant mix, and shopping infrastructure), brands (branding product level and corporate brand), incentives (monetary and non-monetary incentives), communication (advertising, atmosphere, and personal selling), price (low prices and perceived value), and distribution (access from parking, access from the store, proximity to home, proximity to work, spatial distance, and temporal distance). Apart from Blut et al. (2018), other studies (e.g., Arenas-Gaitan et al. 2021; Hanaysha et al. 2021) proposed retail mix instruments, but there is no significant difference from previous studies.

Customer value as a customer’s organism (O)

The aspect of a customer’s organism regarding the retail mix instruments can be understood through customer value (Blut et al. 2018; Moore 2005). Customer value perception is defined as an individual’s evaluation of an object (Holbrook 1994). In this study, it is defined as a customer’s evaluation of an FMCG retail mix instrument. Customer value is multi-dimensional and can be measured in many ways because it involves more than one aspect of value simultaneously in any given situation (Holbrook 1994; Zeithaml et al. 2020). Thus, it can be expected that one retail mix instrument may affect various aspects of value dimensions.

Marketing and service literature have suggested many aspects of value dimensions (see examples in Zeithaml et al. 2020); however, in the retail literature, only utilitarian and hedonic (emotional) values have long prevailed (Rintamäki and Kirves 2017). While utilitarian value reflects shopping with a work mentality, hedonic value is more subjective and personal (Hirschman and Holbrook 1982). Considering the retail shopping experience, utilitarian value consists of task-related, instrumental, and rational, but hedonic value involves recreational, self-purposeful, bargain, and emotional (Babin et al. 1994). Diep and Sweeney (2008) argued that both utilitarian and hedonic value dimensions are derived from stores and products. The former is related to the store’s performance and value for money, while the latter involves emotional and social aspects. Rintamäki and Kirves (2017) noted that utilitarian value can be perceived from prices paid and time and effort saved; meanwhile, hedonic is feelings and emotions aroused by shopping experiences.

Apart from the two prevailing value dimensions, some researchers suggested functional and economic value as distinct values rather than considering both as utilitarian value (Rintamäki et al. 2007; Sheth et al. 1991). Functional value involves quality and price (Carlson et al. 2019; Sheth et al. 1991). Economic value can be perceived as money savings, economical products, reduced prices, lower prices, or the best deal that a retailer offers (Rintamäki and Kirves 2017; Zeithaml 1988). In addition, social value was proposed as one critical value perception within the retail context where customers are associated with one or more social groups, such as family and friends (Lin and Huang 2012; Sheth et al. 1991). It also involves communication and information (Robertson 1967) when customers ask about product details (Lin and Huang 2012). Epistemic value is another value dimension that refers to curiosity, novelty, and knowledge (Sheth et al. 1991); specifically, knowledge has been recognized to influence the customer’s decision in retail (Lin and Huang 2012). Finally, conditional value is the effect of seasonality, situations, time, and place that moderate the level of other value perceptions (Lin and Huang 2012; Sheth et al. 1991).

Customer engagement in the FMCG context as a customer’s response (R)

The concept of customer engagement has been introduced for two decades. The roles and value of customer engagement received particular attention from scholars and business practitioners (Brodie et al. 2011). However, customer engagement is concentrated prominently in service marketing journals but not retail journals (Ng et al. 2020). Although there is no consensus on definitions and conceptualizations of customer engagement, this concept can be examined from four approaches (Ng et al. 2020). Customer engagement as a behavioral manifestation involves any manifestations beyond purchase that result from motivational drivers (van Doorn et al. 2010). Customer engagement as a psychological state occurs through interactive and co-creative customer experiences (Brodie et al. 2011). Customer engagement as a disposition to act is an internal state involving a willingness to engage and leading to a behavioral manifestation (Storbacka et al. 2016). Customer engagement as processes or stages of customer decision-making involves, for example, experience, attitude, and behavior factors that represent rent stages of an engagement process (Maslowska et al. 2016).

Ng et al. (2020) indicated that customer engagement as a behavioral manifestation had been studied most. From this point of view, customer engagement is observed from any behaviors resulting from motivational drivers (van Doorn et al. 2010). Such behaviors include purchases (Kumar and Pansari 2016) and any others that go beyond purchases, such as word of mouth, loyalty, customers’ reviews and recommendations, customer-to-customer interactions, peer-to-peer information sharing, attention and absorption, and customer feedback (Dessart et al. 2016).

Relationships between retail mix instruments (S), customer value perceptions (O), and customer engagement (R)

The relationships between retail mix instruments and customer value dimensions have been identified in the retail literature. Studies have a long tradition of testing the effects of multiple retail instruments when creating customer value perceptions. For instance, O’Cass and Grace (2008) identified the impact of store service provision on the customers’ perception of value for money. Rintamäki et al. (2007) and Kumar et al. (2010) reported that store atmosphere could develop store image and enhance customer value perceptions. Turel et al. (2010) found that customer value perception was built from individual experiences and product/service interactions that were associated with emotional value (Lin and Huang 2012). Tandon et al. (2016) revealed that customers visited retail for economic pursuits. Unsurprisingly, each study was quantitative and explored only some pre-determined retail mix instruments and value dimensions. Considering marketing practices, marketers should not use only one retail mix instrument but should create a compelling retail mix to suit the customers’ behavior and decision process (Hanaysha et al. 2021). This is because the retail mix combines various elements that fulfill customer demand, delight them, and excite their emotion when shopping (Aparna et al. 2018). Therefore, it would benefit practitioners if this study could identify the potential effects of a set of retail mix instruments on various customer value perceptions.

Next, some studies identify the relationships between retail mix instruments and customer engagement. For instance, Ryu and Feick (2007) presented that sales promotions encourage customer participation in engagement, such as customer referrals. Home delivery service (Roy Dholakia and Zhao 2010) and retail location (Solomon 2010) were indicated as essential factors influencing customer engagement. Customer engagement was found to be related to product quality (Gudonavičienė and Alijošienė 2013) and product variety (Dubihlela and Dubihlela 2014). Blut et al. (2018) identified from their meta-analysis that 24 retail mix instruments could influence patronage.

Finally, customer perceived value can influence customers’ behaviors at the post-purchase stage, such as customer-to-customer interactions, referrals, and repurchases (Parasuraman and Grewal 2000). Customer perceived value is specific to the object of evaluation (Holbrook 1994). Specifically, from the perspective of S-O-R, it is subject to stimuli. For example, Cheah et al. (2020) indicated the effect of price image (a customer’s attitude toward price) on customer perceived value. In the FMCG context, the authors found no article suggesting this relationship.

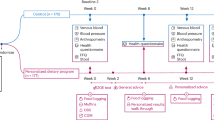

All the studies above highlight interplays among retail mix instruments, customer value perceptions, and customer engagement. According to the S-O-R theory, this study proposes that retail mix instruments (stimuli) can activate the customer value perceptions (cognitive mechanisms), which results in customer engagement (responses) (Fig. 1). In the next section, a qualitative investigation will be used to explore the potential relationships between these three constructs.

Source Authors adapted from Mehrabian and Russell (1974).

Research methodology

This study aims to identify the potential effects of retail mix instruments on customer perceived value and engagement. By using the context of FMCG retail and integrating and extending previous works more comprehensively, the study also aims to add descriptions to the three constructs in the a priori conceptual framework, i.e., to identify themes related to retail mix instruments, customer value perceptions, and customer engagement. A qualitative approach was used to generate rich data. Retail customers can be varied, and different generational cohorts perceive different retail experiences (Parment 2013). Generational cohorts are individuals born in the same period, likely to have similar life patterns, and share similar values (Lyons et al. 2005). This study focused on Generation X (Gen-X) and Y (Gen-Y) due to two reasons: (1) taking a closer look at specific cohorts can offer specific insights for developing future research agenda and contributes to retail marketing practices (Parment 2013) and (2) Gen-X and Gen-Y are deemed essential for consumer behavior studies (Shaw and Fairhurst 2008).

The FMCG retail existing in Thailand includes hypermarkets, supermarkets, and convenience stores (Tunpaiboon 2021). While the convenience stores are small size and the supermarkets focus primarily on fresh foods (Tunpaiboon 2021), this study examined the hypermarkets, specifically the two key players in Thailand: Store-A and Store-B. Convenience sampling and snowballing techniques were used. The first author (hereafter, the researcher) contacted peers and asked the peers to find the others. All contacted persons were screened with two screening questions: their ages and visiting frequency. The informants were Gen-X and Gen-Y and had experience visiting both stores. The researcher explained the research objective, ethical conduct, and their rights and asked informants for consent and if they would participate. In February 2023, interviews were conducted by two means: face-to-face online and on-site at a store location. The informants who joined online were asked to remind them of their recent in-store experiences. Before the interview began, an informant was asked to keep their answers to one retail location.

Interview questions were developed according to (Spradley 1979) (Supplementary Appendix A). The researcher started with questions used to establish rapport with the informants. After connection had been established, open-ended questions related to the study’s research question were employed, starting from exploratory questions, and following questions that specifically emerged after the researcher repeated the informant’s previous answers (i.e., reasons and positive/negative experience regarding retail mix instruments). Specific questions were used to explore smaller aspects of experience regarding retail mix instruments. Sales promotions, a vital instrument for FMCG retail, was selected as an example because customers are often sensitive to this instrument, and marketers often find difficulty when determining sales promotion campaigns (Abolghasemi et al. 2020; Pauwels 2007; Senachai et al. 2023). Delving down into sales promotions may help marketers prioritize sales promotion activities. In addition, to see whether the retail mix instruments proposed in the literature need to be revisited or not due to the impact of COVID-19, the researcher asked the informants’ expectations regarding what the store should do after the COVID-19 ceases its impact.

Field notes were taken, and all interview dialogs and the informants’ answers were recorded. A mixed range of adequate informants led to a broad range of answers at the beginning but seemed to contain similar key information later once the informant pool increased (Hoffman and Maier 1961). A data saturation point was indicated at around the 28th-30th informants. In total, 40 informants were interviewed: 12 informants were interviewed at the store locations, and 28 informants were interviewed online (Supplementary Appendix A). Scholars suggested that saturation is likely to occur around 5-30 informants (Guest et al. 2006).

All interview data was translated verbatim. Following Braun and Clarke (2006), a thematic analysis was conducted to conceptualize themes related to the elements of the a priori conceptual framework. Analyzing and coding were conducted line by line and through every line in the interview transcripts to generate initial codes that were further grouped into categories, and finally, significant themes were indicated. The data sources obtained from the online versus on-site interview approaches were triangulated and mostly showed similar findings (i.e., the first draft of findings).

To propose a conceptual framework of this study, the authors first identified retail mix instruments, dimensions of value perceptions, and engagement behaviors and then added information into the a priori conceptual framework. The authors acted as two investigators who held the social constructionist paradigm and iteratively interpreted and discussed the information in the first draft and revised emergent themes. An extensive literature search was undertaken to provide evidence to support the study’s empirical findings and helped strengthen the final draft of the findings, which is presented in the next section. An inter-judge reliability was estimated (Weber 1990), resulting in a reliability level of 90% and indicating an acceptable level. Finally, a conceptual framework of the study was proposed (see Section “Discussions”).

Marketers must create a compelling retail mix to match the behavior of their customers (Hanaysha et al. 2021). To provide an application of this study, the authors revisited the field notes and analyzed them based on the proposed conceptual framework. The focus was on the application of sales promotions, especially on how sales promotions should be used to encourage the customer’s perceptions and their engagements.

Findings

Findings in this section will be presented based on the S-O-R theory but narrated to represent the complex reality of the phenomena investigated rather than reported concerning each S-O-R component. As emphasized previously in the literature section, the main reason is that a retail mix instrument could stimulate a customer to perceive more than one value dimension and further lead them to more than one engagement behavior. Thus, reporting each retail mix instrument and explaining its effects along the narrative is deemed appropriate. In total, the data revealed 12 retail mix instruments that affected six types of value dimensions and the informants’ engagement behaviors. Empirical evidence is provided in Table 1.

Store reputation

Store reputation refers to the customer’s overall evaluation of a retail store (Berg 2013). Although the informants perceived that Store-B and Store-A sold equivalent items from similar suppliers, they perceived the store’s reputation differently. Each store had its unique value propositions. Customers, especially women shoppers, perceived that Store-A offered superior quality products, except fresh vegetables and fruits. From the informants’ perspectives, Store-A’s reputation for product quality resulted in customers perceiving functional value. Although most informants knew that both stores’ brands had similar or slightly different product prices, they perceived Store-B offered lower prices than Store-A. This led customers to perceive Store-B’s reputation as a better store with lower prices. Evidence showed that the store’s reputation and its product’s quality are interrelated (Yuen and Chan 2010). In addition, the reputations of product quality and prices could be explained by perceived functional and economic value. These store’s value propositions attracted the informants’ interest and were the most effective strategy for the retail understudy.

Product quality

Product quality is a competitive retail advantage; if retailers provide the right products to customers, this can lead to the customer’s future responses and interactions (Blut et al. 2018). Product quality had a relationship with customer engagement and was thus a primary concern of retailers (Yuen and Chan 2010). The findings of this study revealed that product quality was essential when choosing shopping places. The informants would continue to shop at the specific store if it promised good quality products.

Product and brand variety

Low on-shelf availability results in a loss of revenue (Roussos et al. 2002). The findings indicated that, although product variety was associated with higher inventory levels, it could increase sales rates. Most informants emphasized that a store with various products and brands was perceived as convenient for them when shopping, as they could save time and effort, resulting in continued shopping. This can be considered as functional value (convenience) for customers, which could predict their future visits (Dubihlela and Dubihlela 2014), purchase intention (Gupta and Kim 2010; Zeithaml 1988), and retention (Parasuraman and Grewal 2000).

Store layout and shelf arrangement

A simple layout enhanced the speed and efficiency of grocery shopping (Terblanche 2017). The findings indicated that a good layout made it easier for the informants to find products without spending extra time and effort, resulting in increasing their perceived functional value (convenience and time-saving). Some informants also preferred to revisit the store because they knew the layout. Additionally, an improper store layout and shelf arrangement could devalue product quality. One informant saw that the clearance products were not properly arranged, as these looked so cheap, dirty, and damaged. This decreased the perceived functional value of the store’s clearance products.

Store ambiance

The store ambiance increased the customer’s enjoyment (Kent and Omar 2003; Teller et al. 2016), customer experience (Tandon et al. 2016), customer retention (An and Han 2020), and customer engagement (Blut et al. 2018; Pansari and Kumar 2017). In this study, most informants evaluated the store ambiance based on light, air, and cleanliness; however, this was subjective to individuals who valued the atmosphere differently.

The store ambiance had an impact on the informants’ emotions during shopping and their future decisions to revisit the stores. Some informants felt negative emotions resulting from the cleanliness of the toilet, the dim lighting that made it difficult to find products, and the musty air that made them uncomfortable. The ambiance could also affect the store’s reputation (Kumar et al. 2010). Some informants perceived Store-A as a high-end store, compared with Store-B, as its ambiance and atmosphere looked better.

Location and parking facility

Retail location can influence customer engagement (Blut et al. 2018; Solomon 2010). Similarly, the results revealed that the informants often visited the store close to their houses or offices. This locational proximity’s main benefit is a time-saving and shorter journey (Arenas-Gaitan et al. 2021), specifically, functional value or perceived convenience. The informants who preferred shopping on weekdays often visited the store close to their office, while those who enjoyed shopping on weekends went to those close to their houses.

The informants also considered parking facilities when evaluating the store’s location. Parking facilities increase their perceived convenience (functional value) and could reduce their irritation when they go shopping (emotional value). Conversely, they would be dissatisfied and might stop visiting the store if they could not park their cars.

Store variety

Customers might get bored when they come to stores and see the same products, services, and offerings, and this can reduce their spending (Tandon et al. 2016). Retailers must consider having many shops in their locations, as this can increase engagement behaviors (Gilboa et al. 2020). This study defines store variety as a store that groups various shops and other entertainment. The findings of this study further revealed that having many other shops in the store (e.g., restaurants, home decoration shops, and cinemas) increased the informants’ positive feelings towards the stores. Some favored Store-A over Store-B because the former had a cinema and more restaurants. Besides shopping, they could engage in additional activities with their family and friends, resulting in enjoyment and future engagement behaviors. Thus, having a variety of shops in the stores could increase the informants’ perceptions of the function value (i.e., they could do many activities in one place), social value (i.e., they did activities with their peers and family), and emotional value (i.e., gain positive emotions and a sense of belonging), as suggested by Elmashhara and Soares (2020).

Sales promotions

Retailers focus more on selling activities and sales promotions (Pantano 2014). Customers visit the store primarily for economic pursuits (Tandon et al. 2016). The findings suggested that sales promotions helped customers reduce costs, empower their economy, induce actions, and produce superior shopping experiences. The informants perceived that the promoted products they had purchased from the stores were valued for money, regarding the price they paid (economic value), and this resulted in revisiting the store. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Store-A ran discount campaigns for two and a half months, so-called raka-maha-chon (in Thai), by applying a price discount to a product unknown to the customers. Some informants were excited and curious whether their household products would be discounted.

Retailers offer sales promotions for a limited time in an emerging sales promotion strategy (Vakeel et al. 2018). The results in this study indicated that the sales promotions were applied based on four types of time: daily (ready-to-eat), monthly (discount), yearly (membership), and occasionally (raka-maha-chon). According to Sheth et al. (1991), these are considered as conditional values. The findings also highlighted a negative outcome of period-related sales promotions. Sales promotions launched within a limited period (e.g., discount coupons) that expire before customers can use them could negatively affect their emotional value (Vakeel et al. 2018).

The findings highlighted that sales promotions were interrelated with product quality. The informants, who preferred buying quality products from Store-A for themselves or their families, perceived that such products even had more quality if promoted with sales promotion activities. Specifically, the product was even better when discounted compared to when it was sold at a regular price. This means the product has its own functional value, increasing with sales promotions. Additionally, the sales promotions were intertwined with the store’s reputation. Although both stores had similar sales promotion activities, some informants believed that Store-B offered a lower price because of its value proposition regarding everyday low prices. Besides, the more frequently sales promotions offered by Store-B, the more the customers perceived gaining their accumulated economic value. Some also sensed a positive emotion towards the store’s reputation.

When the stores offered sales promotions to the informants, they felt they were essential to the stores and increased their awareness of self-value, resulting in positive emotions towards the store. In sum, sales promotion activities could create economic, emotional, and social value (i.e., recognizing the value of customers), resulting in revisiting the stores, additional purchasing, and following the store’s news. However, the customer’s preference towards sales promotions differed across generational cohorts, suggesting that demographics may affect the customer’s value perceptions.

The findings indicated that sales promotions could negatively impact perception. Some female informants felt the product was less quality when running ready-to-eat food promotions (i.e., half price of ready-to-eat food when the store was nearly closed). The food had been cooked long before the discounts were applied, which was not good during the pandemic. Thus, running lower-price campaigns in some situations could decrease the customer’s perception of product quality. Once again, product quality is intertwined with sales promotions.

Advertising

The informants received both stores’ information from traditional media (television, brochures, stores’ boards, SMS, and posts) and online (Facebook, Line, and the store’s media applications). This information, including clearance spots, price tags, and active sales promotions, was important to the customers. The findings also showed that traditional media were powerful for Gen-X informants, but Gen-Y informants preferred digital media. The SMS even annoyed some Gen-Y male informants. This highlights that using the wrong media with the wrong generational cohorts might decrease perceived emotional value.

Advertising creates interactions between customers and the store (Brodie et al. 2019) and can lead to customer engagement (So et al. 2014). Advertising through social media has become popular and gained much acceptance by most informants. Providing the store’s advertisements, especially sales promotions, through its critical customer touchpoints (e.g., Facebook) created more customer-store interactions and increased the customer’s expertise in shopping, resulting in the customer’s referral (i.e., advertising the store’s information on their individual online community). Additionally, communication channels played a significant role in transferring customer messages. Customers who missed the store’s messages could perceive a decrease in value perception (e.g., emotional, economic, and functional).

Staff service

Most businesses are concerned about service quality (Parasuraman et al. 1988). The results showed that staffs played a vital role in FMCG retail, especially their service mindset and behaviors that affected the customer’s buying experience. The information which the staffs told the customers could lead to specific value perceptions. Most informants in this study noted that training the staffs to service them, especially during peak periods, and informing them of shopping-related information (e.g., the current active sales promotion activities) were essential to the store’s service level. In this case, the information about sales promotions led some informants to perceive the economic and functional value. Interactions between customers and staffs led to additional purchases and customer recommendations (Blut et al. 2018). Thus, the store’s staffs were a vital communication channel in transferring customer messages. The informants in this study claimed that staffs were the store’s competitiveness and could increase their engagement.

Delivery service

The delivery service influences the customer’s attitude and engagement (Crosby et al. 1990; Roy Dholakia and Zhao 2010). The findings revealed further that it helped the customers achieve their shopping plans, especially the informants who did not have time to shop on-site. They enjoyed shopping online because it was convenient; thus, they wanted the store to deliver products quickly. If the store can serve their delivery needs, they will continue to shop at the specific store. The delivery was related to functional value (convenience and logistic), resulting in their retention and engagement.

Not only home delivery service that has an impact on the customer’s channel selection, but also click-and-collect such as drive-through stations (Hübner et al. 2016). The specific delivery method allows customers to buy a product anywhere, from their computers or mobile devices, and collect it at the store without leaving their vehicles (Tamulienė et al. 2020). The drive-through stations are common in Europe, such as France (Hübner et al. 2016), but new for Thais. After the COVID-19 outbreak, the informants needed the store to establish a drive-through service, as this allowed them to keep healthy during the pandemic.

Self-service

Self-service encourages customers to participate actively in the exchange process (Regan 1960) and can help customers reduce time and shopping process as well as makes buying goods convenient (Gauri et al. 2021). The use of self-service kiosks (SSKs), a type of self-service technology, could impact sale patronage (Lee and Lim 2009). In Thailand, SSKs were not widely used in the retail sector before COVID-19. The informants noted that the stores should install SSKs to keep them healthy and increase their convenience.

Discussions

Theoretical discussions

The findings have increased our in-depth understanding of the effect of retail mix instruments on customer perceived value and engagement behaviors. Based on the findings narrated in the previous section, a conceptual framework is proposed by extending the a priori one (Fig. 2) and used to identify potential future research agenda (Table 2).

The findings revealed 12 retail mix instruments acting as stimuli that triggered the customer’s decision process. They are grouped into two: (1) the integrated marketing communication (IMC) tools (sales promotions, advertising, and staff service) and store characteristics (store reputation, product quality, product and brand variety, store layout and arrangement, store ambiance, location and parking facility, store variety, delivery service, and self-service). Although academics and practitioners know these instruments, the classification is novel to the literature. The rationale supporting this classification is provided as follows.

First, marketers use the IMC tools to manage marketing activities and the customer’s needs and move the customers to various stages of the decision process (Raman and Naik 2010). Thus, the IMC is a set of instruments, including advertising, public relations, direct marketing, personal selling, and sales promotions, that retailers use to stimulate the customer’s decision-making (Vantamay 2011). In the proposed framework, all instruments are aligned with what has been suggested in the literature. However, it must be noted that “staff service” is the same as personal selling, which refers to the personal communication of information that aims to persuade customers to buy products (Janjua et al. 2022).

Second, the rest of the instruments are defined as store characteristics and the data show the most common store characteristics suggested in previous studies: quality, variety, availability, environment cues, ambiance, and design (Baker et al. 2002; Tyrväinen and Karjaluoto 2022; Uusitalo 2001). Some others, such as children’s play areas, could affect the customer’s perceived enjoyment (Rajagopal 2009). However, this was not indicated in this study perhaps because of the impact of COVID-19.

Furthermore, the findings highlighted potential interactions between the IMC tools and the store characteristics, resulting in more engagement behaviors; for example, applying sales promotions could increase the perception of product quality compared to the price, resulting in sales rates. While there were few studies revealed the impact of three services (staff service, delivery service, and self-service) on perceived value and engagement behaviors, the findings of this study provided some insights and suggested researchers to investigate further.

Situational factors are proposed as the other stimulus. The impact of COVID-19 was an external stimulus affecting the customer’s decision-making. Recent studies in the retail context identified the impact of COVID-19 as a situational factor influencing the customer’s decision process (Nguyen et al. 2020; Tyrväinen and Karjaluoto 2022). In this study, COVID-19 stimulated the customers to perceive some infectious risks, resulting in demanding service innovations (i.e., drive-through stations and self-service kiosks). These innovations helped guarantee their hygiene and created their perceived functional value, which would increase their future purchases and engagements. Apart from COVID-19, there might be other external stimuli (e.g., customer-to-customer interactions) (Lin et al. 2019), and situational factors (e.g., recession economies, wars, and protests) affecting the retail’s marketing strategies and the customer’s decision-making. These were not found in the current study and should be explored further.

Apart from stimuli, the figure shows that the six types of customer value perceptions (economic, functional, emotional, social, epistemic, and conditional) were the consequences of the 12 retail mix instruments and the impact of COVID-19. The primary driver of consumer choice is functional value (product quality, variety, sales promotions, and convenience), as if they believed shopping was a work to be accomplished. Some researchers argued that customers did not consider the epistemic and conditional value dimensions when purchasing durable goods (Sweeney and Soutar 2001). The findings provided evidence in contrast: sales promotions available for a period could create conditional value. Even when the discount applied to the product unknown to the customer, this led to the customer’s curiosity (epistemic value). There may be other value perceptions, such as environmental value (perceiving that the store’s operation is environmentally friendly) (Kumar 2014), that were not found in this study and might need further investigation.

This study identified some effects of demographics on customer value perceptions, similar to Sheth et al. (1991). Gen-X sometimes selected specific stores due to the availability of other shops, i.e., restaurants where they could dine with family. Thus, retail mix instruments may be intertwined with the customer’s demographic, and both may affect their value perceptions. Furthermore, value dimensions might not be independent but interrelated, as suggested by Sweeney and Soutar (2001). While a few studies observed such relationships (Gallarza et al. 2017; Leroi-Werelds 2019), the findings of this study provided some insights. For example, sales promotions initially affect the customer perceived economic value and might consequently affect their functional value. More specifically, the customer observes a discount price tag and perceives the economic value; they later evaluate the money paid against the expected utility they might obtain from the product, resulting in the perceived functional value.

Finally, the customers under investigation experienced the retail mix instruments holistically, shaping their perceptions and choices as Holbrook (1999) suggested. The findings revealed four engagement behaviors; however, some others (e.g., loyalty, customer-to-customer interactions, and customer feedback) did not emerge from the study and should be explored further. Furthermore, the proposed framework should be extended to include other concepts that are essential to retail strategic management, for instance, customer satisfaction (Bowden 2009), customer experience (Javornik and Mandelli 2012), and customer journey (Gauri et al. 2021).

Marketing practices

Researchers suggested that salespersons are essential in creating customer engagement (Dubihlela and Dubihlela 2014; Solomon 2010). However, sales promotions and communication are critical to retail (Arenas-Gaitan et al. 2021; Mohd-Ramly and Omar 2017). This study showed that the three IMC tools and the store’s characteristics were the retailers’ competitive advantages and affected all six consumption values. For instance, staff informing the customers about sales promotions produced economic and functional value and encouraged them to continue shopping at the stores, buy more, recommend the stores to their families or peers, and follow store news. This may be useful for marketers when creating a strategized mixture of both categories to manage their customers.

Marketers have long been investigating what motivates customers to shop at a store and desire to explain and predict customer behaviors (Sheth et al. 1991). Using an example of sales promotions, this research reports how FMCG retailers may leverage the proposed framework to design strategies that may be used to promote customer engagement behaviors. A list of sales promotion activities that the informants considered necessary is provided in Supplementary Appendix A, and an application of the top-four activities is illustrated in Table 3 to show how marketing strategists may use each sales promotion activity to induce customer value perception and engagement behaviors.

FMCG retailers should offer unique value propositions to customers (Javornik and Mandelli 2012). Previously, researchers suggested that sales promotions could enhance the customer’s perception of the best value for money and augment their shopping experience (Roussos et al. 2002). Table 3 shows that the heart of creating the stores’ value propositions originated from sales promotions, resulting in all value perceptions. All promotional activities created functional and economic value dimensions, while some generated specific value perceptions. Perceived conditional value in terms of time-limited discounts created benefits to both the store (i.e., inducing customers to purchase quickly) and the customers (if they used the discount in time). FMCG retailers should not ignore this value dimension. Offering gifts that the customers wanted could create positive emotions, but the customers might perceive negative emotions if the gift was not of their interest. Memberships could create the customer’s perceived epistemic value, which seems to be the only one inducing their curiosity and encouraged them to follow the store’s news.

The success of sales promotions depends upon the store’s two fundamental abilities: (1) the ability to select a promotional mix that suits target markets and (2) the ability to accurately identify the demographic and behavioral characteristics of target consumers (Gedenk et al. 2010). Based on the findings of this study, a strategized mixture of sales promotions is presented in Table 4. FMCG retailers may use the sales promotions presented in the table to create short and long-term customer engagement behaviors.

Conclusion

This study sought to understand how retail mix instruments influenced customer perceived value and engagement behaviors and to reveal descriptive insights of each concept. Two FMCG retail stores in Thailand were chosen, and forty informants were approached to provide in-depth information about their shopping experiences at the stores. The findings reported descriptive insights into various retail mix instruments, value perceptions, and engagement behaviors and were conceptualized to form a conceptual framework, which is the main theoretical contribution of this study. The future research agenda was proposed to move forwards and the paper’s secondary theoretical contribution.

Contributing to retail marketing practices, sales promotions were chosen to validate an application of the proposed framework and illustrate how marketers may develop a strategized mixture of sales promotion activities. This may initiate an idea for FMCG retailers to develop marketing plans that suit their customer segments.

As with all research, this study has limitations. The proposed conceptual framework needs to be validated with qualitative data. Further study should employ the framework to explore a wider group of customers. The customers may be the other generational cohorts and those with different incomes living in Thailand. The framework may serve as a guideline when exploring customers in other countries. Finally, future research should investigate the retail context beyond the FMCG.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abolghasemi M, Hurley J, Eshragh A, Fahimnia B (2020) Demand forecasting in the presence of systematic events: cases in capturing sales promotions. Int J Prod Econ 230:107892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107892

An MA, Han SL (2020) Effects of experiential motivation and customer engagement on customer value creation: analysis of psychological process in the experience-based retail environment. J Bus Res 120:389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.044

Aparna K, Krishna P, Kumar V (2018) Analysis of retail mix strategies: a special focus on modern retail formats. Int J Eng Tech Mgmt Res 5(5):71–76. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1284588

Arenas-Gaitan J, Peral-Peral B, Reina-Arroyo J (2021) Ways of shopping & retail mix at the Greengrocer’s. J Retail Consum Serv 60:102451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102451

Babin BJ, Darden WR, Griffin M (1994) Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J Consum Res 20(4):644–656. https://doi.org/10.1086/209376

Baker J, Parasuraman A, Grewal D, Voss GB (2002) The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J Mark 66(2):120–141. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.2.120.18470

Berg B (2013) Retail branding and store loyalty: analysis in the context of reciprocity, store accessibility, and retail formats. Springer Gabler, German

Blut M, Teller C, Floh A (2018) Testing retail marketing-mix effects on patronage: a meta-analysis. J Retail 94(2):113–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2018.03.001

Bowden JLH (2009) The process of customer engagement: a conceptual framework. J Mark Theory Pr 17(1):63–74

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res J 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brodie RJ, Fehrer JA, Jaakkola E, Conduit J (2019) Actor engagement in networks: defining the conceptual domain. J Serv Res 22(2):173–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670519827385

Brodie RJ, Hollebeek LD, Jurić B, Ilić A (2011) Customer engagement: conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J Serv Res 14(3):252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

Carlson J, Wyllie J, Rahman MM, Voola R (2019) Enhancing brand relationship performance through customer participation and value creation in social media brand communities. J Retail Consum Serv 50:333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.008

Cheah JH, Waller D, Thaichon P, Ting H, Lim XJ (2020) Price image and the sugrophobia effect on luxury retail purchase intention. J Retail Consum Serv 57:102188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102188

Chen JS, Tsou HT (2012) Performance effects of IT capability, service process innovation, and the mediating role of customer service. J Eng Technol Manag 29(1):71–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2011.09.007

Crosby LA, Evans KR, Cowles D (1990) Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. J Mark 54(3):68–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400306

Deloitte (2023) 2023 retail industry outlook: embrace the changing consumer to bolster growth in inflationary times. Available via Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/retail-distribution-industry-outlook.html. Accessed 24 Dec 2023

Dessart L, Veloutsou C, Morgan-Thomas A (2016) Capturing consumer engagement: duality, dimensionality and measurement. J Mark Manag 32(5-6):399–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1130738

Diep VCS, Sweeney JC (2008) Shopping trip value: do stores and products matter? J Retail Consum Serv 15(5):399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2007.10.002

Dubihlela D, Dubihlela J (2014) Attributes of shopping mall image, customer satisfaction and mall patronage for selected shopping malls in Southern Gauteng, South Africa. J Econ Behav Stud 6(8):682–689. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v6i8.528

Elmashhara MG, Soares AM (2020) Entertain me, I’ll stay longer! The influence of types of entertainment on mall shoppers’ emotions and behavior. J Consum Mark 37(1):87–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-03-2019-3129

Eroglu SA, Machleit KA, Davis LM (2001) Atmospheric qualities of online retailing: a conceptual model and implications. J Bus Res 54(2):177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00087-9

Gallarza MG, Arteaga F, Del Chiappa G, Gil-Saura I, Holbrook MB (2017) A multidimensional service-value scale based on Holbrook’s typology of customer value: bridging the gap between the concept and its measurement. J Serv Manag 28(4):724–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-06-2016-0166

Gauri DK, Jindal RP, Ratchford B, Fox E, Bhatnagar A, Pandey A, Navallo JR, Fogarty J, Carr S, Howerton E (2021) Evolution of retail formats: past, present, and future. J Retail 97(1):42–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.11.002

Gedenk K, Neslin SA, Ailawadi KL (2010) Sales promotion. In: Krafft M, Mantrala M (eds) Retailing in the 21st Century. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-72003-4_24

Gilboa S, Vilnai-Yavetz I, Mitchell V, Borges A, Frimpong K, Belhsen N (2020) Mall experiences are not universal: the moderating roles of national culture and mall industry age. J Retail Consum Serv 57:102210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102210

Gudonavičienė R, Alijošienė S (2013) Influence of shopping centre image attributes on customer choices. Ekon vadyb 18:545-552. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.em.18.3.5132

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X0527

Gupta S, Kim HW (2010) Value‐driven Internet shopping: the mental accounting theory perspective. Psychol Mark 27(1):13–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20317

Hanaysha JR, Al Shaikh ME, Alzoubi HM (2021) Importance of marketing mix elements in determining consumer purchase decision in the retail market. Int J Serv Sci Manag Eng Technol 12(6):56–72. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJSSMET.2021110104

Hirschman EC, Holbrook MB (1982) Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J Mark 46(3):92–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600314

Hoffman LR, Maier NR (1961) Quality and acceptance of problem solutions by members of homogeneous and heterogeneous groups. Abnorm Soc Psychol 62(2):401. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044025

Holbrook MB (1994) The nature of customer’s value: an axiology of service in consumption experience. In: Rust RT and Oliver RL (eds), Service quality: new directions in theory and practice. Sage, Thousand Oaks, p 21-71. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229102.n2

Holbrook MB (1999) Consumer value: a framework for analysis and research. Routledge, London

Hübner AH, Kuhn H, Wollenburg J (2016) Last mile fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel grocery retailing: a strategic planning framework. Int J Retail Distrib 44(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2014-0154

Hunt SD (2014) Marketing theory: foundations, controversy, strategy, and resource-advantage theory. Routledge, London

Janjua PR, Tabassum N, Nayak BS (2022) The marketing practices of Walt Disney and Warner Media: a comparative analysis. In: Bhabani SN, Naznin T (eds) Modern corporations and strategies at work. Springer, Singapore, p 93-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-4648-6

Javornik A, Mandelli A (2012) Behavioral perspectives of customer engagement: an exploratory study of customer engagement with three Swiss FMCG brands. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 19:300–310. https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2012.29

Kent T, Omar O (2003) Customer service. In: Tony K, Ogenyi O (eds) Retailing. Red Globe Press, London, p 432-459. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-37410-2

Kumar I, Garg R, Rahman Z (2010) Influence of retail atmospherics on customer value in an emerging market condition. Gt Lakes Her 4(1):1–13

Kumar P (2014) Greening retail: an Indian experience. Int J Retail Distrib 42(7):613–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-02-2013-0042

Kumar V, Pansari A (2016) Competitive advantage through engagement. J Mark Res 53(4):497–514

Laato S, Islam AN, Farooq A, Dhir A (2020) Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: the stimulus-organism-response approach. J Retail Consum Serv 57:102224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102224

Lee SM, Lim S (2009) Entrepreneurial orientation and the performance of service business. Serv Bus 3:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-008-0051-5

Leroi-Werelds S (2019) An update on customer value: state of the art, revised typology, and research agenda. J Serv Manag 30(5):650–680. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-03-2019-0074

Levy M (1999) Revolutionizing the retail pricing game. Discount Store N. 38:15

Lin M, Miao L, Wei W, Moon H (2019) Peer engagement behaviors: conceptualization and research directions. J Serv Res 22(4):388–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670519865609

Lin PC, Huang YH (2012) The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J Clean Prod 22(1):11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.10.002

Liu-Thompkins Y, Khoshghadam L, Shoushtari AA, Zal S (2022) What drives retailer loyalty? A meta-analysis of the role of cognitive, affective, and social factors across five decades. J Retail 98(1):92–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2022.02.005

Lyons S, Duxbury L, Higgins C (2005) Are gender differences in basic human values a generational phenomenon? Sex Roles 53:763–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7740-4

Maslowska E, Malthouse EC, Collinger T (2016) The customer engagement ecosystem. J Mark Manag 32(5-6):469–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1134628

McKinsey (2022) The execution imperative for European consumer-goods companies. Available via McKinsey. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/ourinsights/the-execution-imperative-for-european-consumer-goods-companies. Accessed 24 Dec 2023

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974) An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press, Massachusetts

Mittal A, Jhamb D (2016) Determinants of shopping mall attractiveness: the Indian context. Procedia Econ Financ 37:386–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(16)30141-1

Mohd-Ramly S, Omar NA (2017) Exploring the influence of store attributes on customer experience and customer engagement. Int J Retail Distrib 45(11):1138–1158. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-04-2016-0049

Moore M (2005) Towards a confirmatory model of retail strategy types: an empirical test of Miles and Snow. J Bus Res 58(5):696–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.09.004

Ng SC, Sweeney JC, Plewa C (2020) Customer engagement: a systematic review and future research priorities. Australas Mark J 28(4):235–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2020.05.004

Nguyen HV, Tran HX, Van Huy L, Nguyen XN, Do MT, Nguyen N (2020) Online book shopping in Vietnam: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Publ Res Q 36:437–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-020-09732-2

O’Cass A, Grace D (2008) Understanding the role of retail store service in light of self‐image-store image congruence. Psychol Mark 25(6):521–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20223

Pansari A, Kumar V (2017) Customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences. J Acad Mark Sci 45:294–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0485-6

Pantano E (2014) Innovation drivers in retail industry. Int J Inf Manag 34(3):344–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.03.002

Parasuraman A, Grewal D (2000) The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: a research agenda. J Acad Mark Sci 28(1):168–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300281015

Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J Retail 64(1):12–40

Parment A (2013) Generation y vs. baby boomers: shopping behavior, buyer involvement and implications for retailing. J Retail Consum Serv 20(2):189–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.001

Paul J, Sankaranarayanan KG, Mekoth N (2016) Consumer satisfaction in retail stores: theory and implications. Int J Consum Stud 40(6):635–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12279

Pauwels K (2007) How retailer and competitor decisions drive the long-term effectiveness of manufacturer promotions for fast moving consumer goods. J Retail 83(3):297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2006.03.001

Rajagopal (2009) Growing shopping malls and behaviour of urban shoppers. J Retail Leis Prop 8:99–118. https://doi.org/10.1057/rlp.2009.3

Raman K, Naik PA (2010) Integrated marketing communications in retailing. In: Krafft M, Mantrala M (eds) Retailing in the 21st Century. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, p 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-72003-4_26

Regan WJ (1960) Self-service in retailing. J Mark 24(4):43–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296002400408

Rintamäki T, Kirves K (2017) From perceptions to propositions: profiling customer value across retail contexts. J Retail Consum Serv 37:159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.07.016

Rintamäki T, Kuusela H, Mitronen L (2007) Identifying competitive customer value propositions in retailing. Manag Serv Qual Int J 17(6):621–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710834975

Robert D, John R (1982) Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach. J Retail 58(1):34–57

Robertson TS (1967) The process of innovation and the diffusion of innovation. J Mark 31(1):14–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296703100104

Roussos G, Tuominen J, Koukara L, Seppala O, Kourouthanasis P, Giaglis G, Frissaer J (2002) A case study in pervasive retail. In: WMC’02: proceedings of the 2nd international workshop on mobile commerce, Atlanta, Georgia. https://doi.org/10.1145/570705.570722

Roy Dholakia R, Zhao M (2010) Effects of online store attributes on customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions. Int J Retail Distrib 38(7):482–496. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011052098

Ryu G, Feick L (2007) A penny for your thoughts: referral reward programs and referral likelihood. J Mark 71(1):84–94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.1.084

Senachai P, Julagasigorn P, Chumwichan S (2023) The role of retail mix elements in enhancing customer engagement: evidence from Thai fast-moving consumer goods retail sector. ABAC J 43(2):106–124. https://doi.org/10.14456/abacj.2023.18

Shaw S, Fairhurst D (2008) Engaging a new generation of graduates. Educ Train 50(5):366–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910810889057

Sheth JN, Newman BI, Gross BL (1991) Why we buy what we buy: a theory of consumption values. J Bus Res 22(2):159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8

So KKF, King C, Sparks B (2014) Customer engagement with tourism brands: scale development and validation. J Hosp Tour 38(3):304–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012451456

Solomon MR (2010) Consumer behaviour: a European perspective. Pearson education, Harlow

Spradley J (1979) The ethnographic interview. Holt Rinehart & Winston, New York

Storbacka K, Brodie RJ, Böhmann T, Maglio PP, Nenonen S (2016) Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation. J Bus Res 69(8):3008–3017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.034

Sweeney JC, Soutar GN (2001) Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale. J Retail 77(2):203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

Tamulienė V, Rašimaitė A, Tunčikienė Ž (2020) Integrated marketing communications as a tool for building strong retail chain brand loyalty: case of Lithuania. Innov Mark 16(4):37–47. https://doi.org/10.21511/im.16(4).2020.04

Tandon A, Gupta A, Tripathi V (2016) Managing shopping experience through mall attractiveness dimensions: an experience of Indian metro cities. Asia Pac J Mark 28(4):634–649. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2015-0127

Teller C, Wood S, Floh A (2016) Adaptive resilience and the competition between retail and service agglomeration formats: an international perspective. J Mark Manag 32(17-18):1537–1561. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1240705

Terblanche NS (2017) Customer interaction with controlled retail mix elements and their relationships with customer loyalty in diverse retail environments. J Bus Retail Manag Res 11(2):1–10. https://doi.org/10.24052/JBRMR/252

Theatro (2023) 2023 retail customer experience survey. Available via Theatro. www.theatro.com/resources/report/theatro-2023-retail-customer-experience-survey. Accessed 24 Dec 2023

Tunpaiboon N (2021) Industry outlook 2021-2023 modern trade. Available via Krungsri Research. https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/industry-outlook/wholesale-retail/modern-trade/io/io-modern-trade. Accessed 24 Dec 2023

Turel O, Serenko A, Bontis N (2010) User acceptance of hedonic digital artifacts: a theory of consumption values perspective. Inf Manag 47(1):53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2009.10.002

Tyrväinen O, Karjaluoto H (2022) Online grocery shopping before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analytical review. Telemat 71:101839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101839

Uusitalo O (2001) Consumer perceptions of grocery retail formats and brands. Int J Retail Distrib 29(5):214–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550110390995

Vakeel KA, Sivakumar K, Jayasimha K, Dey S (2018) Service failures after online flash sales: role of deal proneness, attribution, and emotion. J Serv Manag 29(2):253–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2017-0203

van Doorn J, Lemon KN, Mittal V, Nass S, Pick D, Pirner P, Verhoef PC (2010) Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions. J Serv Res 13(3):253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

Vantamay S (2011) Performances and measurement of integrated marketing communications (IMC) of advertisers in Thailand. J Glob Manag 1(1):1–12

Verhoef PC, Noordhoff CS, Sloot L (2023) Reflections and predictions on effects of COVID-19 pandemic on retailing. J Serv Manag 34(2):274–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-09-2021-0343

Wang Y, Xu R, Schwartz M, Ghosh D, Chen X (2020) COVID-19 and retail grocery management: insights from a broad-based consumer survey. IEEE Eng Manag Rev 48(3):202–211. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMR.2020.3011054

Weber RP (1990) Basic content analysis (2nd ed). Sage publications, California

Wongkitrungrueng A, Assarut N (2020) The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J Bus Res 117:543–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.032

Yu W, He M, Han X, Zhou J (2022) Value acquisition, value co-creation: the impact of perceived organic grocerant value on customer engagement behavior through brand trust. Front Psychol 13:990545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.990545

Yuen EF, Chan SS (2010) The effect of retail service quality and product quality on customer loyalty. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 17:222–240. https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2010.13

Zeithaml VA (1988) Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Mark 52(3):2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

Zeithaml VA, Verleye K, Hatak I, Koller M, Zauner A (2020) Three decades of customer value research: paradigmatic roots and future research avenues. J Serv Res 23(4):409–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520948134

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS: Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. PJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research based on the Belmont Report and GCP in Social and Behavioral Research, Thailand (Record No.4.3.01: 32/2565; Reference No. HE653290). This study does not involve the collection or analysis of data that could be used to identify participants. Thus, all informants is anonymized and the submission does not include any identification of person. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Participants were informed of the study’s purpose and their rights and were asked to provide consent before participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Senachai, P., Julagasigorn, P. Retail mix instruments influencing customer perceived value and customer engagement: a conceptual framework and research agenda. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 145 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02660-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02660-y