Abstract

This study examines the effect of Knowledge Management (KM) processes on organizational performance in Saudi Arabian service organizations. It focuses on knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application, and examines their effects on quality, operational, and innovation performance. While the service sector can enhance operational efficiencies through effective KM implementation, the extent of this impact, particularly in terms of quality and operational performance in developing countries like Saudi Arabia, remains underexplored. The study uses a quantitative methodology, obtaining 605 valid responses from Saudi service sector managers through an online self-reported questionnaire. Structural equation modeling validates the research model and tests the hypotheses. Results indicate that knowledge sharing has a nonsignificant effect, while knowledge creation, capture, and application have substantial impacts. Specifically, knowledge application significantly improves operational performance, while knowledge creation influences quality and innovation performance. Organizations are advised to understand their KM processes’ structure to effectively implement and leverage their impact on performance. Emphasizing knowledge sharing through personalized communication channels, employee development opportunities, and effective incentive systems is recommended to sustain engagement and motivation. Furthermore, prioritizing KM tools and technology for seamless knowledge flow across organizational levels and implementing collaborative tools can enhance innovative capabilities, adaptability, and competitive advantages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global economy is currently undergoing a significant shift from an industry-based model to a knowledge-based model (Al mulhima, 2020; Dzenopoljac et al., 2016; Tarhini et al., 2015). Consequently, organizations are increasingly dependent on their knowledge-based assets to establish and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage. Moreover, in today’s global economy, an organization’s capacity to generate and effectively utilize knowledge has emerged as a pivotal factor, influencing its growth and long-term survival (Alvarenga et al., 2020; Ashok et al., 2021; Khadir-Poggi and Keating, 2015).

Knowledge is a crucial asset for organizational success (Abbasi et al., 2021; Ashok et al., 2021; Fletcher-Brown et al., 2021; Ing-Long and Jian-Liang, 2014; Swan and Newell, 2000). By effectively managing knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application, organizations can enhance their performance and foster innovation, thereby achieving a sustainable competitive advantage (Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Asiaei and Bontis, 2019; Dávila and Dos Anjos, 2021; Joshi and Chawla, 2019; Ngoc-Tan and Gregar, 2018; Nikabadi et al., 2016; Thneibat et al., 2022). Moreover, an organization’s competitive advantage increasingly depends on its ability to learn and manage knowledge more effectively than its competitors (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al mulhima, 2020; Muthuveloo et al., 2017; Yen and Shatta, 2021).

Evaluating and measuring knowledge management (KM) performance is critical for justifying investments in KM initiatives (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Muthuveloo et al., 2017; Yen and Shatta, 2021). KM performance measurements enable organizations to review reports, identify issues, set new goals, and establish future directions, which enhances decision-making skills and competitive positioning. Additionally, these measurements support setting benchmarks and adopting best practices (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Ashok et al., 2021; Fletcher-Brown et al., 2021). Therefore, organizations need to develop precise KM performance measurements to ensure that the intended goals of KM initiatives are achieved (Abbasi et al., 2021; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Ashok et al., 2021; Fletcher-Brown et al., 2021; Ing-Long and Jian-Liang, 2014; Swan and Newell, 2000).

Studies on KM processes and organizational performance have been a central focus for researchers and practitioners for years (Al mulhima, 2020; Alzuod, 2020; Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar, 2016; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Researchers have emphasized the crucial role KM plays in organizational success, impacting various levels, including employees, processes, products, and the organization itself (Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar, 2016; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Additionally, KM has the potential to produce interrelated effects across these four levels (Al mulhima, 2020; Alzuod, 2020; Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar, 2016; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Consequently, organizations recognize KM as a vital component for gaining a competitive advantage and adapting to economic transformations. However, few studies have explored the impact of KM processes on organizational performance in developing countries (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al mulhima, 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021). These studies have primarily focused on the manufacturing and technology industries (Alaaraj et al., 2016; Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Alzuod, 2020; Jermsittiparsert and Boonratanakittiphumi, 2019) and on countries other than Saudi Arabia (Al mulhima, 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Moreover, while quality and operational performance are crucial indicators in evaluating KM implementation (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Chong, 2006; Gholami et al., 2013), limited research has examined their relationship with KM processes (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Miandar et al., 2020). Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of KM processes’ effect on organizational performance is required (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al mulhima, 2020; Miandar et al., 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021).

The service sector, characterized by highly specialized knowledge, can significantly benefit from effective KM implementation. Such an implementation can enhance sector efficiency through cost reduction and increases in sales and profits. Most importantly, it ensures the sector’s ability to develop and sustain a competitive edge (Saba, 2020). Nevertheless, the influence of KM on organizational performance in terms of quality, operational, and innovation performance in the service sector has not yet been fully explored, particularly in developing countries, such as Saudi Arabia (Alaaraj et al., 2016; Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Alzuod, 2020; Jermsittiparsert and Boonratanakittiphumi, 2019). The service sector in Saudi Arabia has garnered increased attention since the launch of Vision 2030, holding significant potential for growth and contributing to the country’s income (GASTAT, 2023). Thus, investigating the effects of KM processes on the sector’s performance becomes critical. Prior studies have emphasized the need for further research to comprehend how KM processes can enhance the service sector’s capacity for innovation and performance improvement (Al mulhima, 2020; Areed et al., 2021; Aydın and Erkılıç, 2020).

The current study aims to empirically examine the effect of KM processes on the quality, operational, and innovation performance of public and private organizations within Saudi Arabia’s service sector. The primary contributions of this study are twofold. First, it develops a comprehensive KM framework that examines the effects of KM processes on organizational performance, specifically focusing on quality, operational, and innovation performance. Previous research has emphasized the need for such a framework, especially in investigating the impact of KM processes in developing countries (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Second, this study provides empirical evidence of the effects of KM processes on organizational performance in both the public and private sectors within Saudi Arabia’s service industry. Previous research has confirmed the significant effect of KM processes on organizational performance (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al mulhima, 2020; Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Yen and Shatta, 2021).

Our study builds upon the findings of previous studies on KM conducted by Abusweilem and Abualous (2019), Al Ahbabi et al. (2019), Buranakul et al. (2016), Jankelova and Joniaková (2021), and Nguyen et al. (2022). These studies have already demonstrated the substantial benefits that organizations can achieve through the effective implementation of KM processes. By ensuring information accuracy, organizations can avoid costly mistakes and capitalize on opportunities for improvement and growth, leading to enhanced productivity, improved quality, increased innovation, and better decision-making in operational processes. These findings underscore the vital role played by KM processes in driving positive organizational outcomes.

Our study aims to provide valuable insights and empirical evidence that further substantiate the positive influence of KM processes on various aspects of organizational performance. Through rigorous data analysis and empirical investigation, we focus on areas such as productivity, efficiency, innovation, decision-making, and operational processes. By examining these diverse dimensions, we aim to offer a comprehensive understanding of the broad impact that KM processes can have on organizational performance. Furthermore, our study seeks to advance the theoretical foundations of KM by expanding the understanding of how these processes enable organizations to effectively leverage their knowledge assets, promote continuous learning, and foster a culture of improvement. By adding empirical evidence to the existing knowledge base, we aim to strengthen the theoretical frameworks in the field of KM and provide a more robust foundation for future research and practical applications.

The paper is structured as follows: Section “Literature review” provides a critical synthesis of the literature review on KM processes and organizational performance. Section “Framework development and hypotheses” explains the development of the research model and hypotheses that include KM processes, quality, operational, and innovation performance. Section “Research methodology” presents the research methodology. Section “Data analysis and results” provides the data analysis and assesses the structure model and the results of the hypotheses testing. Section “Discussion” discusses the study’s findings. Lastly, Section “Conclusion” presents the study’s implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature review

Knowledge management

Knowledge has become a valuable intangible asset that organizations can use to improve innovation processes and gain a sustainable competitive advantage (Ing-Long and Jian-Liang, 2014; Tarhini et al., 2015). Knowledge also includes information, experience, and insight that are useful to individuals and organizations.

KM is a multidisciplinary field, and researchers have developed various definitions based on the discipline and the scope of the study, such as management, information technology, accounting, and education (Girard and Girard, 2015; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015). The following is a discussion of the definitions of KM by different studies.

A study conducted by Duhon (1998) describes KM as a field that supports an integrated method of discovering, recording, assessing, recovering, and sharing organizational information assets. In the same vein, Skyrme and Amidon (1997) define KM as the explicit and systematic administration of knowledge, including its creation, gathering, organizing, distribution, usage, and exploitation (transforming individual knowledge into organizational knowledge) throughout an organization. KM could be further described as a set of practices, initiatives, and techniques that organizations employ to produce, preserve, share, and utilize knowledge to improve organizational performance (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). The two studies by Turban et al. (2003) and Pearlson and Saunders (2004) developed a more process‐oriented definition. Turban et al. (2003) explain KM as the process of collecting, creating, and facilitating knowledge sharing to support its effective application in organizations. Similarly, Pearlson and Saunders, (2004) define KM as four primary processes: knowledge generation, capture, codification, and transfer among individuals and groups.

Knowledge management processes

KM processes are essential practices that organizations perform to process and develop their knowledge assets (Holsapple and Joshi, 2000). Some studies label KM processes as activities, practices, or capabilities (Elezi and Bamber, 2016; Lee et al., 2012; Susanty et al., 2019), while others refer to them as KM processes (Dzenopoljac et al., 2018; Obeidat et al., 2016). Even though they have been labeled differently, they refer to the same concept (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). Studies have addressed different models of KM processes, as presented in Table 1. These models view KM differently in terms of concept and the number of processes. However, the majority view KM as a four-process model that includes creating knowledge internally or acquiring it externally, capturing and storing it in the organizational repository, sharing and disseminating it across different organizational levels, and finally utilizing it by applying the obtained knowledge to various business practices. This study identifies four KM processes: knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application (Alavi and Leidner, 2001). Despite their interdependence, the four processes are distinct and often occur as part of a continuous KM cycle. The creation of knowledge allows for knowledge to be captured, which is then shared so that knowledge can be applied. Through knowledge application, lessons learned can be used to generate new knowledge, resulting in an ongoing cycle of KM and continuous improvement (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015).

This study adopted Alavi and Leidner’s (2001) definition of KM. The nature of the four KM processes is accurately explained as follows:

-

Knowledge creation is the process of producing new knowledge content or updating already-existing content that is part of the explicit or tacit knowledge of an organization (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). It is the organizational capability to generate novel ideas from existing data, information, and resources to optimize organizational performance (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995).

Knowledge creation is affected by different factors, such as opportunity, motivation, and capability, and must be highlighted by organizations to ensure the effective creation of knowledge (Hutchinson and Quintas, 2008; Obeidat et al., 2016; Shujahat et al., 2017). Locke et al. (1997) and Ahmed et al. (2020) emphasize the importance of engaging employees and giving them the opportunities to express their thoughts and participate in decision-making processes. Furthermore, improving collaboration among employees (Mona et al., 2016; Nonaka, 1994; Nor et al., 2012) and providing brainstorming sessions (Hutchinson and Quintas, 2008; Obeidat et al., 2016) have been found to be efficient ways to increase employees’ engagement, which in turn leads to the creation of new knowledge. In addition, developing a reward framework that recognizes new and innovative ideas is an effective way to motivate employees and promote knowledge creation (Altinay et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2021).

-

Knowledge capture refers to the process of retrieving organizational knowledge (both explicit and tacit) from different sources, such as organizational repositories, people, artifacts, and organizational entities (Wagner and Zubey, 2005; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015). This process entails the creation and integration of knowledge into an organization’s knowledge repository (Dalkir, 2005; Korimbocus et al., 2020).

Knowledge capture can be influenced by several factors, such as technology infrastructure and the availability of resources for documentation and training (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Korimbocus et al., 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Organizations can benefit from current technology to capture, store, codify, and update knowledge securely and easily (Korimbocus et al., 2020). For example, using digital platforms such as a KM portal provides easy and quick access to the required information, and ensures all employees have access to the required knowledge. In addition, providing training programs equips employees with the skills and abilities required to capture knowledge effectively (Sarwat and Abbas (2020); Setiawan and Yuniarsih, 2020).

-

Knowledge sharing is the process of disseminating explicit and tacit knowledge among individuals, groups, and organizations (Lee, 2001) and facilitating work processes, acquisition of new skills, and knowledge intensity (Lee et al., 2005). It is possible to share knowledge in a variety of ways, including training sessions, workshops, collaboration platforms, and information and communication technologies (ICT), as well as communities of practice (Ahmad and Karim, 2019; Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015).

Several factors can influence the implementation of knowledge sharing (Eaves, 2014). These include opportunities to share, motivation, and culture. This study further argues that these factors can foster an environment that facilitates and encourages knowledge sharing among employees. Employees are motivated to actively participate in knowledge when they are given rewards, whether monetary or non-monetary, and are more willing to share their knowledge and expertise with colleagues when their efforts are recognized and rewarded. As a result, when employees are motivated to share their knowledge, this prevents critical knowledge from being lost when they leave the organization (Eaves, 2014). Furthermore, fostering a culture of knowledge sharing, where knowledge sharing becomes a norm within the organization, results in a more knowledgeable and competent workforce, which enhances overall performance (Arnold et al., 2000; Coyte et al., 2012; Kremer et al., 2019).

-

Knowledge application is the process of using the knowledge shared within the organization to support business functions and processes to make decisions and perform tasks that have clear results, such as better products and services (Becerra-Fernandez and Sabherwal, 2015; Obeidat et al., 2016). For information to be applied successfully, an individual or team must possess the necessary skills, competencies, and contextual understanding (Lee and Kim, 2017; Vel et al., 2018). According to Massingham (2014), knowledge application practices contribute to efficiency by reducing errors and saving time.

Studies have identified several important factors for the effective implementation of knowledge applications (Carro Saavedra et al., 2015; Miguel et al., 2016; Song et al., 2005; Ranjbarfard et al., 2014). These factors include individual characteristics and the environment where the knowledge application process occurs (Carro Saavedra et al., 2015; Miguel et al., 2016; Ranjbarfard et al., 2014). Individual characteristics include motivation, cognitive ability, and previous experience. Individuals who are highly motivated, high in cognitive ability, and have prior knowledge or experience in the domain of shared knowledge are more likely to engage effectively in the learning activities and application process (Carro Saavedra et al., 2015; Miguel et al., 2016; Song et al., 2005; Ranjbarfard et al., 2014). Regarding environmental factors, two in particular can facilitate or hinder the effective implementation of knowledge applications: physical (i.e., the availability of resources and technology) and social (i.e., organizational culture and norms such as open communication and trust) (Carro Saavedra et al., 2015; Miguel et al., 2016; Ranjbarfard et al., 2014).

KM and organizational performance in the service sector

Organizational performance can be defined as the level of an organization’s success (Chelliah et al., 2010). On the other hand, Sandybayev (2019) defined organizational performance as an organization’s capability to exist and achieve certain objectives within a desirable balance of costs and benefits. These different definitions focus on two aspects of organizational performance: achieving organizational goals and survival, both of which can be achieved through effective KM implementation (Al-Hakim and Hassan, 2016; Choi et al., 2008; Dalkir, 2013; Gunasekaran et al., 2004).

KM can significantly contribute to organizational performance by offering various benefits. Several studies have found that the effective implementation of KM improves decision-making (Acharya et al., 2018; Danish et al., 2013; Djanegara et al., 2018), enhances knowledge retention and innovation, and increases intellectual capital (Akram et al., 2011; Marina, 2007). Furthermore, Kašćelan et al. (2020) and Mas-Machuca et al. (2020) claimed that organizations that effectively managed their knowledge provided better customer services. In the same vein, ALSarhani (2016) and Wijaya and Suasih (2020) found that effective KM implementation supports organizations in being more adaptable and competitive in their industries, thus gaining a competitive advantage in the long run.

A limited number of studies investigated the effect of KM on the service sector performance (Alaaraj et al., 2017; Migdadi, 2020; Shahnawaz and Zaim, 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021). A few focus on the whole sector (Alaaraj et al., 2017; Al mulhima, 2020; Migdadi, 2020; Shahnawaz and Zaim, 2020), while the majority only consider a specific service such as telecommunication (Abd-Elrahman et al., 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021), tourism and hospitality (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2015; Kaldeen and Nawaz, 2020), financial and banking services (Kiprotich et al., 2015), or healthcare services (Leal et al., 2018; Tang, 2017).

Studies that investigate the effects of KM processes on organizational performance have emphasized the important role that KM processes play in improving performance in different contexts (Alaaraj et al., 2017; Kaldeen and Nawaz, 2020; Shahnawaz and Zaim, 2020). Alaaraj et al. (2017) found that knowledge acquisition, sharing, and utilization have a significant effect on Malaysia’s service sector performance. Similarly, studies conducted by Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) and Migdadi (2020), in UAE and Jordan, respectively, found that knowledge creation has the highest impact on organizational performance. Some studies claim that KM processes can improve service delivery quality, customer satisfaction, and innovation performance (Abd-Elrahman et al., 2020; Migdadi, 2020; Shahnawaz and Zaim, 2020; Yen and Shatta, 2021), while others argue that the effectiveness of KM processes is context-dependent and may not always translate into measurable outcomes (Antunes and Pinheiro, 2020; Austin et al., 2008; Ntawanga et al., 2020; Storey and Barnett, 2000). The implementation of KM, according to Alavi and Leidner (2001), is critical to the success of service organizations because the quality of service provided is highly reliant on employees’ skills, knowledge, and expertise.

Other studies focus on the antecedents of KM processes and how they leverage the KM processes’ effects on service sector performance (Kaldeen and Nawaz, 2020; Shahnawaz and Zaim, 2020). Several factors are identified by Shahnawaz and Zaim (2020) and Kaldeen and Nawaz (2020), such as employees’ engagement, leadership support, technology used, and employees’ capabilities. A study, performed by Shahnawaz and Zaim (2020) on service-based organizations in Turkey, reveals that organizational success in KM is positively impacted by employees’ engagement in knowledge-sharing behavior and managerial leadership support, which in turn improves innovation performance and, ultimately, financial performance. In the same vein, a study conducted by Kaldeen and Nawaz (2020) examines the effect of KM processes on organizational performance in star-rated hotels in Sri Lanka. The study found that information technology and human resource capabilities strengthen the positive effects of KM processes on organizational performance. Furthermore, Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) and Fernandez Miguel et al. (2016) claim that effective communication and collaboration mechanisms can facilitate knowledge sharing and application among employees across organizational levels.

Studies of KM and organizational performance in Saudi Arabia

Studies of KM and organizational performance have gained a wider interest because of Saudi Arabia’s transformation into a knowledge-based economy (Abdulfatah and Adeinat, 2019; Albassam, 2019; Alhazmi, 2018; Alnashri, 2015; Gharamah et al., 2018). A few studies, including this one, examine the effects of KM processes on service sector performance in Saudi Arabia. Most, however, focus on barriers and issues related to KM practices (Abdulfatah and Adeinat, 2019; Albassam, 2019; Alhazmi, 2018; Alnashri, 2015) and the strategic importance of KM (Gharamah et al., 2018), while limited studies investigate the effects of KM processes on organizational performance (Azyabi, 2018; Attia and Salama, 2018; Yen and Shatta, 2021).

A few studies investigate the effects of KM processes on organizational performance in terms of quality, operational, and innovation performance, as presented in Table 2. The studies were conducted in different industries, but all of them used a survey-based quantitative approach to collect the data, except for Alsereihy et al. (2012), who used a case study approach (Alsereihy et al., 2012; Azyabi, 2018; Attia and Salama, 2018; Yen and Shatta, 2021). Alsereihy et al. (2012) discuss several case studies of KM strategic implementation and how KM impacted performance in terms of productivity, turnaround time, and organizational efficiency. The study found that knowledge sharing is the most important concept in developing KM solutions because the success of KM initiatives depends on employee willingness to participate and engage in these programs (Alsereihy et al., 2012). In addition, a study conducted by Azyabi (2018) examines the impact of KM processes on Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) performance in terms of customer satisfaction and financial performance. The study found that KM processes improve SME performance. On the other hand, a recent study was conducted by Yen and Shatta (2021) in the telecommunication industry to explore the factors that impact the effective implementation of KM to improve telecommunication industry performance. The study observed that telecommunication organizations lack innovation capability as employees are not interested in contributing and sharing their insights in service design and development because they are concerned about losing their superiority even if rewards are offered. They propose that, for successful KM initiatives, telecommunication organizations should promote a culture that encourages innovation and engagement where employees are willing to make, and take responsibility for, the decisions that affect their jobs. None of the aforementioned studies have investigated the effect of knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application on quality, operational, and innovation performance. Thus, more research is required in the context of Saudi Arabia to effectively implement KM and accurately evaluate its effect on organizational performance.

Framework development and hypotheses

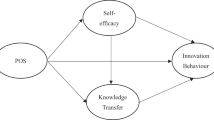

The first aim of this study is to examine the effects of the four KM processes on quality performance, the second is to investigate their effects on operational performance, and the third is to look at their effects on innovation performance. This study builds upon the theory of knowledge-based view (KBV) (Grant, 1996) and is conceptualized based on prior studies by Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) and Obeidat et al. (2016). The proposed research model is depicted in Fig. 1. The independent variables are KM processes (knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application) that directly affect the dependent variables: namely quality performance and operational performance.

Knowledge is regarded as an important, unique, and rare asset in the KBV theory (Grant, 1996). The KBV assumes that organizations exist because they are better positioned to manage knowledge than their competitors (Grant, 1996). Knowledge is also viewed as a strategic organizational resource that can be used to enhance competitiveness by managing exploration and exploitation in a manner that produces and sustains a competitive advantage (Grant, 1996; Sahibzada et al., 2020). Merat and Bo (2013) state that KBV has two primary components: organizational knowledge, which must be valuable, non-imitable, and rare, and KM processes, which should be in place to enable the creation, capture, sharing, and application of knowledge (Grant, 1996; Shujahat et al., 2019). Moreover, KBV emphasizes the importance of high coordination and the integration of employee learning within an organization (Kogut and Zander, 1992).

Based on the KBV, organizations with more advanced knowledge resources are more likely to be able to adapt to evolving business environments, thus enabling them to leverage new ideas, services, and products (Shahzad et al., 2016). Additionally, the KBV theory emphasizes the importance of implementing effective KM processes within organizations. Organizations can enhance their innovation capabilities by managing knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application effectively. These processes enable organizations to generate new knowledge, solve complex problems, access relevant information for informed decision-making, and adapt to changing conditions. Additionally, the successful implementation of KM processes contributes to organizations’ ability to leverage employee knowledge, utilize external resources, and foster a culture of continuous learning and innovation (Jermsittiparsert and Boonratanakittiphumi, 2019; Shahzad et al., 2016).

KM processes and quality performance

Quality is a fundamental characteristic of products, and high-quality products are those that satisfy consumer needs (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Juran, 2004). According to Flynn et al. (1994), quality management is a combination of methods to attain and maintain high-quality results. The goal of quality management is to prevent inadequacies at all organizational levels and for all organizational functions while meeting the expectations of consumers (Akdere, 2009; Loke et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2008).

Knowledge is considered a crucial component in the quality-management processes that help organizations maintain continual enhancement and performance excellence. Several studies emphasize the significance of KM as a foundation for enhancing quality processes (Akdere, 2009; Loke et al., 2012). In addition, Lyons et al. (2008) assert that KM activities associated with KM processes, such as planning, execution, and performance assessment, are crucial to maintaining quality enhancement.

The relationship between quality management and KM is viewed from two different perspectives (Honarpour et al., 2012). The first perspective views KM as an enabler for quality management, and the second views quality management as a supporter of KM processes. This study focuses on the first perspective, from which KM processes are viewed as an enabler for quality management, because this study aims to evaluate the effects of KM processes on quality performance (Honarpour et al., 2012).

A limited number of studies have discussed the effects of KM processes on quality performance (Abd-Elrahman et al., 2020; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Devi et al., 2021; Kašćelan et al., 2020; Mas-Machuca et al., 2020). Effective implementation of KM processes can improve quality performance in several ways (Akdere, 2009; Honarpour et al., 2012). Knowledge creation encourages problem-solving and the development of new insights, which help identify and share best practices and standard operating procedures among employees (Abd-Elrahman et al., 2020; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). Knowledge capture enhances quality performance by preserving and documenting best practices, lessons learned, and expertise within an organization to promote consistency and efficiency in tasks (Devi et al., 2021; Kašćelan et al., 2020; Mas-Machuca et al., 2020). Knowledge sharing can facilitate the dissemination of expertise and insights among employees. It allows individuals to learn from each other, which reduces duplication of effort and promotes a shared understanding of best practices. This collaborative method improves problem-solving, accelerates decision-making, and increases overall efficiency (Abd-Elrahman et al., 2020; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). The accumulated knowledge and experience can be applied to support organizations in identifying recurring quality issues by analyzing the related information to identify the root cause of the issue, solve it, and prevent similar issues in the future (Devi et al., 2021; Kašćelan et al., 2020; Mas-Machuca et al., 2020). This practical experience helps create a workforce that is more adaptable and efficient, which improves quality outcomes as individuals use their knowledge to solve problems and optimize procedures. Therefore, it is essential to conduct further studies to comprehend the effects of KM processes on quality performance. Based on the previous arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1-A. Knowledge creation has a positive effect on quality performance.

H2-A. Knowledge capture has a positive effect on quality performance.

H3-A. Knowledge sharing has a positive effect on quality performance.

H4-A. Knowledge application has a positive effect on quality performance.

KM processes and operational performance

Operational performance is defined by Voss et al. (1997) as the measurable aspect of the outcomes of organizational processes. On the other hand, operational performance is defined by Flynn et al. (2010) as the improvement that occurs in response to a fluctuating and highly competitive environment. Operational performance is a nonfinancial organizational performance dimension that can be measured by several dimensions that reflect internal operational processes in terms of process quality, product and service delivery, efficiency, and productivity (Abdelwhab et al., 2019).

In the literature, a few studies have investigated the impact of KM processes on operational performance (Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Fugate et al., 2009; Pin and Yew, 2015). Some were conducted in a Western context (Fugate et al., 2009), while others were performed in an Eastern context (Pin and Yew, 2015; Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019). A study by Fugate et al. (2009) examines the effect of the KM processes of logistic operational personnel on operational performance in US manufacturing organizations. The findings indicate that a common interpretation of data gathered by logistics operations staff is crucial for a timely and united reaction to changes in the business environment (Fugate et al., 2009). A study by Pin and Yew (2015) used data gathered from Malaysia’s manufacturing organizations and found that KM processes improve operational performance in terms of cost and time reduction, as well as productivity. A different study was conducted by Abusweilem and Abualous (2019) on the banking sector in Jordan. The findings revealed that the effective application of KM enhances organizations’ capability to learn more quickly than their competitors and achieve their strategic goals (Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019).

KM is critical for improving operational performance and increasing organizational efficiency (Chen, 2016). Effective implementation of knowledge creation helps organizations to facilitate the required knowledge resources to perform operational tasks and improves operational efficiency (Pin and Yew, 2015; Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). In addition, knowledge capture enhances operational performance by systematically acquiring and documenting useful information, insights, and best practices within an organization. It enables employees to acquire the necessary knowledge and resources needed to perform operational procedures faster and with higher quality, resulting in improved operational performance (Abdelwhab, 2019). Knowledge sharing enhances operational performance by fostering collaboration, encouraging communication, and leveraging collective expertise. It encourages a deeper understanding of operational challenges and enables the creation of effective strategies (Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). Effective application of KM processes enhances organizations’ capability to learn more quickly than their competitors and identify the best practices, which in turn can improve operational performance (Abusweilem and Abualous, 2019). Based on the previous argument, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1-B. Knowledge creation has a positive effect on operational performance.

H2-B. Knowledge capture has a positive effect on operational performance.

H3-B. Knowledge sharing has a positive effect on operational performance.

H4-B. Knowledge application has a positive effect on operational performance.

KM processes and innovation performance

There are several definitions of innovation in the current literature (Nyström, 1993). Innovation, according to Aboelmaged (2012), is the process of directly connecting novel ideas to the development of a recently initiated good, service, or process. Another definition, developed by Marina (2007), defines innovation as the process of creating new information and concepts to promote innovative business outcomes for optimizing internal organizational procedures and structures, and to develop market-driven products and services. Organizations must take into account the innovation aspect when formulating their business strategies to create and maintain their competitive edge (Marina, 2007).

KM creates an environment that stimulates innovation (Marina, 2007). Innovation is the integration of an organization’s existing knowledge resources to create new knowledge (Mardani et al., 2018). Therefore, an organization’s capability to innovate relies on its internal abilities, such as its own knowledge, technological base, and skills in finding, adopting, and expanding created knowledge (Obeidat et al., 2016).

Several studies have found that KM processes enhance innovation performance (Chun‐Yao et al., 2012; Migdadi, 2020; Obeidat et al., 2016). These studies highlighted KM’s vital role in strengthening organizations’ innovative capabilities (Chun‐Yao et al., 2012; Migdadi, 2020; Obeidat et al., 2016). Effective KM processes can help organizations to improve innovation performance via several approaches (Migdadi, 2020; Obeidat et al., 2016; Sofiyabadi et al., 2022; Thneibat et al., 2022). Knowledge creation facilitates innovation by encouraging the generation of new insights and solutions via research and experimentation, stimulating creativity. This creative thinking fosters learning in organizations and leads to the development of innovative products, processes, or services (Alshanty et al., 2019). Knowledge capture ensures that employees have access to the right information to make informed decisions, leading to more innovative and effective solutions (Migdadi, 2020; Obeidat et al., 2016). In addition, effective knowledge sharing facilitates the dissemination of information and insights by providing platforms and tools that encourage collaboration and communication and allow employees to learn from each other and develop innovative solutions. It increases the organizations’ ability to explore and exploit potential knowledge resources, which in turn improves innovation capability (Elbeltagi and Al-husseini, 2015). Moreover, knowledge application helps organizations to support continuous improvement by providing feedback and analysis on innovation performance, which enables organizations to identify areas for improvement (Sofiyabadi et al., 2022; Thneibat et al., 2022). Thus, KM processes can help organizations ensure that they have the right employees, resources, and information to achieve better innovation performance. Based on the previous argument, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1-C. Knowledge creation has a positive effect on innovation performance.

H2-C. Knowledge capture has a positive effect on innovation performance.

H3-C. Knowledge sharing has a positive effect on innovation performance.

H4-C. Knowledge application has a positive effect on innovation performance.

Research methodology

This study examines KM processes’ effects on organizational performance by measuring employees’ perceptions. The study follows a quantitative approach and hence will use a survey-based research methodology. Previous related studies that examine the effects of KM effectively applied a survey-based research methodology (Khan et al., 2018; Al Ahbabi et al., 2019). A diagram that summarizes the methodological approach and data analysis procedure is depicted in Fig. 2. A detailed description of each stage is presented in the subsections that follow.

Population and sample

The targeted population is the employees of public and private organizations in Saudi Arabia’s service sector, including governmental, semi-governmental, and private organizations. The service sector is becoming one of the most significant sectors in the economy of Saudi Arabia (GASTAT, 2019). The service sector contributed 55% to the gross domestic product in 2020, according to the General Authority for Statistics (2022). The service sector contains a wide range of organizations providing specific services that individuals and organizations need (Cuadrado-Roura, 2013). These organizations offer various services that are divided into seven categories: (1) Transportation or storage services; (2) Government services; (3) Wholesale, retail, restaurant, or hotel services; (4) Finance, insurance, consultancy, or business services; (5) Real estate services; (6) Health care services; (7) Telecommunications or information technology services.

The target respondents are employees at managerial levels: top-level managers such as chief executive officers (CEOs), middle-level managers such as branch managers, and operative-level managers such as supervisors. Managers are assumed to have specific knowledge about KM processes and their organizational performance (Shabbir and Gardezi, 2020; Sun et al., 2021).

Survey instrument

The questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The questionnaire is divided into three sections and contains 33 questions. The first section, demographic information, includes eight questions about respondents’ background, experience, and current organization. The second section has fourteen questions about the organization’s KM processes for the four variables: knowledge creation, capture, sharing, and application. Finally, the third section has eleven questions about the respondent’s perception of their organization’s performance in terms of quality, operations, and innovation. All the measures for the seven constructs are adapted from previous studies, as outlined in Table 3.

Data collection

The questionnaire was executed through an online survey, and the data was collected from November 25, 2021, until March 30, 2022. The participants were invited through a web link to a questionnaire. According to GASTAT, no available data identifies organizations in the service sector (GASTAT, 2020). Consequently, there is no available sampling frame that can be used to identify all the possible participants, which is a vital step in the probability sampling technique. Thus, the appropriate sampling technique is the non-probability purposive sampling technique (Saunders et al., 2016). The participants were selected based on the following characteristics: the position they hold (i.e., top-level managers, middle-level managers, and operative-level managers), the potential to have related knowledge about the current practices of KM processes and their organization’s performance, and their organizations must fit under one of the seven service categories. In addition, the questionnaire was distributed to potential participants in different organizations that represent the seven service categories in Saudi Arabia’s service sector to ensure the representativeness of the population.

Even though there are no general guidelines for identifying the sample size for studies employing structural equation modeling (SEM), Kline (2011) suggested a minimum sample size around 200 participants. Nonetheless, Field (2005) demonstrates that a sample size of 300 or more is best to avoid sampling errors in research. The study collected 605 responses.

Data analysis and results

The following are the results from the statistical analysis of the data collected in accordance with the study’s objectives. The results of the descriptive analysis are presented first (demographic information, profile of service sector organizations, and descriptive statistics), followed by the analysis of the seven constructs via Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Then the validity and reliability of the constructs were assessed to evaluate the measurement model. Finally, the hypotheses were tested using covariance-based SEM, with SPSS Amos (version 26).

Demographic information

Table 4 presents the frequencies and percentages of the managers, their respective positions, and organizations. It was revealed that higher positions are dominated by males (86%), whereas women occupy only 14%. This finding is expected since the initiative of women’s empowerment only started a few years ago with the establishment of Vision 2030 in 2016. Moreover, the government’s efforts to achieve equality between men and women in the workplace are executed in various fields and job positions (‘Saudi Arabia National Portal.’, 2022). In addition, most of the managers were middle-level managers (n = 341, 56%) between 30 to 39 years (n = 321, 53%) with a bachelor’s degree (n = 312, 52%). Furthermore, the most frequently observed category of work experience was 11–15 years (n = 152, 25%), whereas the most frequently observed category of experience at the current organization was two years or less (n = 224, 37%).

Profile of service sector organizations

The profile of the service sector organizations that participated in the questionnaire is depicted in Fig. 3. There are three types of organizations: government, semi-government, and private organizations. The respondents included 118 managers from the government, 216 managers from semi-government, and 271 from private organizations. Most participants were from private organizations (n = 271, 45%) that offered telecommunications or information technology services (n = 146, 24%). Additional frequencies and percentages are presented in Table 4.

Descriptive statistics

Tables 5 and 6 show the mean (\(\bar{{\rm{x}}}\)) and standard deviation (SD) of the items for the seven constructs. The implementation of KM is moderate, as the mean values of the four processes did not exceed 4.00, indicating that managers, generally, agree that there is still room for improving KM processes in service sector organizations. Knowledge creation received the highest score (KC1), whereas knowledge capture received the lowest score (KCs1). In general, KM processes implementation is consistent as the SD ranged from 0.85 to 1.02. Regarding service sector performance, mean scores ranged from 3.68 to 4.13; innovation performance received the highest score (IP1), whereas operational performance received the lowest score (OrP2). In addition, the SD ranged from 0.76 to 1.02, indicating consistency in the responses.

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA was performed to assess the overall model fit. The CFA model includes seven constructs and 25 items. The following fit indices were used to assess the model fit: Chi-square goodness of fit test, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Incremental fit indices (IFI). The evaluation of CFA’s model fit indices revealed a good model fit (GOF: χ2 = 569.877; RMSEA = 0.045; CFI = 0.961; IFI = 0.961), and all the indices were above the recommended thresholds (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Dimitrov, 2012; Hair et al., 2016). Moreover, the standardized regression weights of all indicators were above 0.5 and significant at P < 0.001 (Table 2). The results indicate that the assumed relationships between latent factors and their items are valid, and the CFA model fits the data adequately. Thus, the instrument can now be evaluated for construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminate validity.

Validity and reliability

The measurement quality of this study is evaluated by examining convergent validity, discriminant validity, and internal consistency. Three criteria recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981) are used to assess convergent validity. First, all the standardized regression weights were above the recommended value of 0.05 and significant at P < 0.01 (refer to Table 7). Second, the composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach alpha (α) were used to assess the construct reliability. The CR values for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.6, and the Cronbach’s alpha (α) values for all constructs were above the recommended level of 0.70, indicating that internal consistency is achieved (Hair et al., 2016). Third, to establish convergent validity, CR must be greater than 0.6, and the average variance extracted (AVE) value should be greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2016). As presented in Table 8, the CR and alpha values were all greater than 0.70, and the AVE values exceeded 0.5 for all constructs, which indicates the constructs support convergent validity and internal consistency (Hair et al., 2016).

To establish discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE value for a construct must be greater than its correlations with the rest of the constructs (Hair et al., 2016). As shown in Table 8, the discriminant validity was held for all constructs except for knowledge sharing (KS) and knowledge application (KA) constructs, yet the difference between the square root of the AVE for knowledge sharing and its correlation with knowledge application was too small, 0.02, then it could be ignored (Hamid et al., 2017). Therefore, the measurement model results show that reliability, convergent validity, and discriminate validity are established.

Common method variance (CMV)

Before proceeding with the structural model, the data were checked for CMV (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Harman’s single-factor technique was employed to analyze CMV. The result showed that only 36.91% of data variation could be explained by a single factor, which means that CMV is not a significant issue in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In order to assess CMV, the common latent factor model was also employed: CMV = 0.502 = 25%, which is smaller than 50%, emphasizing the same finding of Harman’s single-factor test (Simmering et al., 2014).

The effect of control variables

In this section, the effects of demographic variables, namely gender, age, work experience, level of education, and types of organizations, are analyzed. These variables might interfere with the causal relationship between independent and dependent variables because previous studies have indicated a potential interference in the relationship between KM processes and organizational performance (Donate and Sánchez de Pablo, 2015; Janssen, 2000). Thus, the effects of these demographic variables are tested on the four dependent variables in the SEM model. The results are outlined in Table 9.

The First dependent variable is quality performance. The demographic variables age (β = 0.018, p = 0.791), gender (β = 0.009, p = 0.824), work experience (β = −0.012, p = 0.868), and level of education (β = −0.061, p > 0.05) had no effect on quality performance. However, types of organizations had a positive effect on quality performance (β = 0.214, p < 0.001). The second dependent variable is operational performance. The demographic variables age (β = −0.089, p = 0.207), gender (β = 0.002, p = 0.954), work experience (β = 0.096, p = 0.180), level of education (β = −0.009, p > 0.05), and types of organizations (β = 0.078, p = 0.054) had no effect on operational performance. The third dependent variable is innovation performance. The demographic variables age (β = −0.012, p = 0.849), gender (β = −0.046, p = 0.205), work experience (β = −0.029, p = 0.642), and level of education (β = −0.006, p > 0.05) had no effect on innovation performance. However, types of organizations had a positive effect on innovation performance (β = 0.090, p = 0.012). Even though types of organizations positively impacted some of the dependent variables, the relationships (hypotheses) in the SEM model were not affected when these variables were included in the model. Therefore, there is no need to control these demographic variables.

Structural modeling and hypotheses testing

The structural model was developed based on the measurement model and revealed a good fit considering fit measures as in Fig. 4 (Hair et al., 2016; Hu and Bentler, 1999). The standardized regression weights were above the threshold values of β > 0.5, as presented in Table 7. The results indicate that the assumed relationships between latent variables and their items are valid, and the measurement model fits the covariance matrix well. The study tested 12 hypotheses using the structural model to investigate the effect of KM processes on the three performance indicators (i.e., quality, operational, and innovation performance).

The effect of knowledge creation on organizational performance

The results support all three knowledge creation effect hypotheses (Table 10). Furthermore, the results of H1-A, H1-B, and H1-C demonstrate that knowledge creation has a high impact on innovation performance (β = 0.589), a moderate impact on quality performance (β = 0.300), and a low impact on operational performance (β = 0.246). These results are consistent with the studies by Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) and Migdadi (2020), who found that knowledge creation has the highest impact on innovation performance.

The effect of knowledge capture on organizational performance

The results show that all three knowledge capture hypotheses are supported, as shown in Table 11. Based on the results of H2-A, H2-B, and H2-C, knowledge capture has a positive but minimal impact on innovation performance (β = 0.275), quality performance (β = 0.241), and operational performance (β = 0.214). The results are consistent with those of Al Ahbabi et al. (2019), who discovered that capturing knowledge internally (from employees) and externally (from customers and suppliers) supported organizations in improving the quality of service delivery.

The effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance

The study found a nonsignificant relationship between knowledge sharing and organizational performance. Based on Table 12, hypotheses H3-A, H3-B, and H3-C are not supported. These results contradict some previous studies (Alkhazali et al., 2019; Brahami, 2020; Kordab et al., 2020) though agreeing with other studies focused on different contexts, such as Jilani et al. (2020) investigation into the sustainable performance of banks operating in Bangladesh and Ngoc-Tan and Gregar’s (2018) and Sahibzada et al. (2020) investigation into the KM and organizational performance improvements in Vietnam and Chinese universities respectively. The divergence above points to the existence of factors blocking knowledge sharing toward successful organizational performance, also under the studied context.

The effect of knowledge application on organizational performance

Table 13 confirms the three knowledge application hypotheses. The results demonstrate that the effect of knowledge application is slightly higher on operational performance (β = 0.327) than on quality performance (β = 0.187) and innovation performance (β = 0.265). These results are consistent with previous studies conducted by Rehman et al. (2015) on Pakistani firms and Migdadi et al. (2017) on Jordanian manufacturing and service organizations.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that knowledge creation, capture, and application positively effect organizational performance in terms of quality, operational, and innovation performance. However, knowledge sharing does not show a significant effect on organizational performance. The following sections discuss these findings in detail.

Effect of knowledge creation on organizational performance

The research supports all three hypotheses related to knowledge creation. The outcomes of H1-A, H1-B, and H1-C indicate that knowledge creation has the most substantial effect on innovation performance (β = 0.589, p < 0.05). The effect is moderate on quality performance (β = 0.300, p < 0.05) and low on operational performance (β = 0.246, p < 0.05). These findings align with research by Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) and Migdadi (2020), who observed that knowledge creation most significantly affects innovation performance.

Compared to other KM processes (i.e., capture and application), knowledge creation exerts the greatest influence on quality and innovation performance. This conclusion is in line with a study by Al Ahbabi et al. (2019) in the UAE’s public sector, which found that knowledge creation’s impact on organizational performance was more pronounced than that of knowledge capture, sharing, and application. The positive effect of knowledge creation on organizational performance can be attributed to organizations’ reliance on their employees’ knowledge and experience (Kiprotich et al., 2015; Migdadi, 2020).

Two factors may contribute to knowledge creation’s pronounced effect on innovation performance: organizational culture and Vision 2030 (Auernhammer and Hall, 2014; Pei, 2008). An organization’s culture can either facilitate or impede knowledge creation. Cultures that foster openness, cooperation, and learning are more conducive to knowledge-creation efforts (Auernhammer and Hall, 2014; Pei, 2008). Several studies, including those by Auernhammer and Hall (2014) and Pei (2008), have investigated methods to enhance knowledge creation in organizations, finding that a culture of organizational learning fosters creativity and innovation. Vision 2030 has heightened organizations’ interest in knowledge creation, as organizations are coming to recognize that generating new knowledge is crucial for maintaining a competitive edge and fostering value creation, wealth, and sustainable growth (Vision 2030 Projects, n.d.). Additionally, Saudi Arabia has launched several government initiatives to encourage innovation across various sectors. There is a growing focus on employee development, with support and training for talented individuals. Recently, some organizations have begun establishing creativity and innovation centers within their KM departments to attract and retain talented individuals. These developments highlight an increasing awareness of the importance of human capital in enhancing knowledge-based assets.

Effect of knowledge capture on organizational performance

This study confirms all three hypotheses related to knowledge capture. The results for H2-A, H2-B, and H2-C indicate that knowledge capture has the highest effect on innovation performance, though it is still minor (β = 0.275, p < 0.05), followed by quality performance (β = 0.241, p < 0.05), and operational performance (β = 0.214, p < 0.05). These findings are in line with Djanegara et al. (2018), who reported that the accounting systems in Indonesian ministries and government agencies enhanced knowledge capture, subsequently improving organizational performance. Additionally, the results concur with Al Ahbabi et al. (2019), who found that capturing knowledge from internal (employees) and external (customers and suppliers) sources aided organizations in increasing productivity and service quality.

Capturing knowledge from both internal (employees) and external (competitors) sources is essential for organizations to avoid repeating past mistakes and wasting resources on previously successful projects (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Saqib et al., 2017). The effectiveness of knowledge capture on organizational performance can be influenced by two main factors: the tools and techniques used for knowledge capture (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Saqib et al., 2017) and employee training (Goudarzv and Chegini, 2013; Sarwat and Abbas, 2020; Setiawan and Yuniarsih, 2020). It is critical for organizations to ensure that knowledge is accurately recorded, documented, and stored in knowledge repositories using appropriate tools (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Saqib et al., 2017). Effective systems and tools can ensure that critical knowledge is retained and documented for future reference, saving time and effort. Furthermore, training employees in the use of these tools is essential for their effective implementation (Goudarzv and Chegini, 2013; Sarwat and Abbas, 2020; Setiawan and Yuniarsih, 2020).

Effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance

This study found that knowledge sharing has a nonsignificant effect on organizational performance. The three hypotheses, H3-A (β = −0.034), H3-B (β = −0.095), and H3-C (β = −0.133), are not supported (p > 0.05). These results contradict the findings of some prior studies (Alkhazali et al., 2019; Brahami, 2020; Kordab et al., 2020). For instance, Alkhazali et al. (2019) discovered that effective total quality management (TQM) and human resource practices enhance the effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance. Additionally, Brahami (2020) found that the implementation of suitable customer relationship management (CRM) systems facilitates knowledge sharing among organizational members, thereby improving performance. However, several studies align with the current study’s findings. Jilani et al. (2020) observed that knowledge sharing had a nonsignificant effect on the sustainable performance of bank operations due to employees’ tendency to withhold knowledge from their peers. Ngoc-Tan and Gregar (2018) and Sahibzada et al. (2020) suggest that the nonsignificant relationship between knowledge sharing, and organizational performance does not negate the role of knowledge sharing in performance improvement but rather indicates that other factors might influence this relationship.

Three factors may underlie the nonsignificant effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance in the service sector: tools and technology (Brahami, 2020; Buheji and Al-Zayer, 2010; Buheji, 2010), reward systems (Kremer et al., 2019; Thneibat et al., 2022), and employees’ willingness and ability to share knowledge (Alzuod, 2020; Jilani et al., 2020; Lee and Wong, 2015). Technological tools used for knowledge sharing might not meet organizational needs (Brahami, 2020; Buheji and Al-Zayer, 2010; Buheji, 2010). Studies by Buheji and Al-Zayer (2010) and Buheji (2010) indicated that the government in the Kingdom of Bahrain faced challenges in implementing KM, particularly in knowledge-sharing practices, daily meetings, and the lengthy retrieval of knowledge. Moreover, a well-structured rewards system can inspire employees to seek out new information and use it to the benefit of the organization, facilitating the creation and maintenance of competitive advantage (Kremer et al., 2019). Furthermore, employees’ willingness and ability to share knowledge, often hindered by fears of replacement, low self-esteem, and lack of incentives, are crucial (Alzuod, 2020). Lee and Wong (2015) note that employees are more inclined to share knowledge and experience when they do not fear losing their status. Enhancing these three factors could promote knowledge sharing in service organizations and improve its effect on organizational performance.

Effect of knowledge application on organizational performance

This study supports all three knowledge application hypotheses. The results for H4-A, H4-B, and H4-C demonstrate that knowledge application has a moderate impact on operational performance (β = 0.327, p < 0.05). However, its impact is low on quality performance (β = 0.187, p < 0.05), and innovation performance (β = 0.265, p < 0.05). These findings align with Rehman et al. (2015), who observed that effective knowledge application enabled organizations to identify improvement areas by providing feedback and analysis on innovation performance. This process enhanced innovation capability and subsequently improved organizational performance in Pakistani firms. Likewise, Migdadi et al. (2017) discovered that knowledge application enhanced financial, operational, and product quality in Jordanian manufacturing and service organizations. The study attributed these improvements to organizations’ engagement in KM processes (including knowledge creation, storage, documentation, application, and acquisition) and market orientation (encompassing customer orientation, competitor orientation, and inter-functional coordination). This engagement led to a better understanding of market needs and customer requirements, resulting in quicker responses to market changes. Additionally, involvement in KM processes and market orientation facilitated the identification and sharing of best practices and standard operating procedures among employees, improving quality performance.

Two primary antecedents of knowledge application might explain this low effect: knowledge capture and KM strategic planning (Song et al., 2005). Knowledge capture, a critical precursor to knowledge application, was found to have a low effect on organizational performance. Furthermore, clear long-term strategic planning supported by an R&D budget is necessary for applying the acquired knowledge. According to Chen and Kim (2023), knowledge mobility is an innovation factor that contributes to organizations’ innovation during economic transformation, and organizations should create active talent admission policies, R&D subsidy systems, and better knowledge protection legislation in order to promote the flow of innovative factors. In addition, Kaldeen and Nawaz (2020) and Tran et al. (2022) suggest that organizations in transitional economies should develop appropriate knowledge application strategies to respond to dynamic environments. Their studies found that knowledge application facilitates the development of innovative solutions for challenging issues and supports accurate decision-making, enabling organizations to adapt to changing environments.

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the effect of KM processes on organizational performance within the service sector of Saudi Arabia. The service sector is characterized by its reliance on specialized knowledge, and effective implementation of KM practices can enhance sector efficiency and establish a sustainable competitive advantage (Saba, 2020). Despite its significance, the relationship between KM processes and organizational performance in the service sector remains largely unexplored on a global scale (Alaaraj et al., 2016; Al Rashdi et al., 2019; Alzuod, 2020; Areed et al., 2021; Ashok et al., 2016; Jermsittiparsert and Boonratanakittiphumi, 2019), specifically in developing countries like Saudi Arabia (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Al mulhima, 2020; Aydin and Erkiliç, 2020; Phung et al., 2017).

The study presents four significant implications for organizations aiming to enhance their KM processes and improve performance in the service sector:

Firstly, the findings highlight the importance of assessing the effects of KM processes on quality, operations, and innovation performance. By evaluating the impact of KM initiatives, organizations can determine the effectiveness of their programs and make informed decisions regarding resource allocation. This assessment enables organizations to justify investments in KM programs and facilitates better decision-making.

Secondly, the study emphasizes the substantial impact of knowledge creation on quality and innovation performance, surpassing the impact of other KM processes. Knowledge creation plays a critical role as the foundational stage in KM processes, particularly in service organizations. Strengthening knowledge creation capabilities empowers organizations to provide more innovative and high-quality services, giving them a competitive advantage.

Thirdly, the research reveals that knowledge application plays a prominent role in improving operational performance compared to knowledge creation and capture. Effective implementation of knowledge applications is crucial for enhancing productivity, service quality, delivery, and customer satisfaction within service organizations. Focusing on optimizing knowledge application processes can yield significant operational improvements.

Fourthly, the study indicates that the current knowledge-sharing processes in service organizations have an insignificant effect on organizational performance. This highlights the need for organizations to prioritize factors that influence the implementation of knowledge sharing, such as organizational structures and KM tools and technologies. Previous research has shown that optimizing these elements can amplify the effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance (Afsar and Umrani, 2020; Kaldeen and Nawaz, 2020; Khan et al., 2021; Li and Zheng, 2014; Natineeporn et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2022; Yuan and Woodman, 2010).

It is important to acknowledge and address the limitations of this study. Firstly, the study does not account for personal factors such as trust and employees’ attitudes toward knowledge sharing. Previous research has established that these factors can employ a significant influence on the knowledge-sharing process (Kmieciak, 2021; Phung et al., 2019). By not incorporating these variables, the study may not capture the full complexity and degree of knowledge sharing within organizations. Secondly, the data collection method employed in this study involved the use of a self-reported questionnaire. While this approach offers valuable insights, it introduces the CMV (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, it is worth noting that CMV tests were conducted, and the results indicate that CMV is not a significant concern in this study. Nonetheless, future research could consider utilizing alternative data collection methods to mitigate potential biases associated with self-report measures. Furthermore, the findings derived from purposive sampling may have limited generalizability. The selected respondents may not fully represent the entire population under study (Saunders et al., 2016). To address this limitation and enhance the representativeness of the sample, respondents were selected from all seven categories that comprise the service sector in Saudi Arabia, as outlined in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) report of 2020 (GASTAT, 2020). This approach aims to ensure a more diverse and comprehensive representation of the service sector in Saudi Arabia. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the effects of KM processes on organizational performance within the service sector context. Future research endeavors should consider addressing the identified limitations to further enhance the understanding of knowledge sharing dynamics and their effect on organizational outcomes.

The findings of this study open several avenues for future research. A key insight is the perception among service sector managers of the importance of KM processes in enhancing organizational performance. Therefore, future studies could explore different sectors, such as manufacturing, to generalize the results of this study to other sectors in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, future research could build upon this study by investigating the impact of KM infrastructure on organizational performance in service organizations. For instance, examining how the use of KM tools and technology can amplify the effects of KM processes on organizational performance would be worthwhile. This study observed a nonsignificant effect of knowledge sharing on organizational performance and proposed several potential reasons for this finding, including KM tools and technology, reward systems, and leadership. Future research could delve into the impact of these factors as antecedents of KM processes and their influence on organizational performance. Moreover, while this study assessed organizational performance in terms of quality, operational, and innovation performance, it would be intriguing for future research to investigate the effect of KM processes on different performance indicators, such as financial performance and market share. This would enable a comparison of the influence of KM processes on both financial and nonfinancial performance indicators. This study used questionnaires as the primary tool for data collection to examine the effects of KM processes on organizational performance. Future studies should consider conducting a qualitative study to gain deeper insight into the factors influencing the effect of KM processes on organizational performance. Employing interviews and focus groups with managers can provide detailed information about why KM processes have specific effects on organizational performance.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

References

Abbasi SG, Shabbir MS, Abbas M, Tahir MS (2021) HPWS and knowledge sharing behavior: the role of psychological empowerment and organizational identification in public sector banks. J Public Aff 21(3):174–184.e2512

Abd-Elrahman A-E, El-Borsaly A, Hafez E, Hassan S (2020) Intellectual capital and service quality within the mobile telecommunications sector of Egypt. J Intellect Cap 21(6):1185–1208

Abdelwhab Ali A, Panneer Selvam DDD, Paris L, Gunasekaran A (2019) Key factors influencing knowledge sharing practices and its relationship with organizational performance within the oil and gas industry. J Knowl Manag 23(9):1806–1837

Abdulfatah FH, Adeinat IM (2019) Organizational culture and knowledge management processes: case study in a public university. VINE J Inf Knowl Manag Syst 49(1):35–53

Aboelmaged M (2012) Harvesting organizational knowledge and innovation practices: An empirical examination of their effects on operations strategy. Bus Process Manag J 18:712–734

Abusweilem M, Abualous S (2019) The impact of knowledge management process and business intelligence on organizational performance. Manag Sci Lett 9(12):2143–2156

Acharya A, Singh SK, Pereira V, Singh P (2018) Big data, knowledge co-creation and decision making in fashion industry. Int J Inf Manag 42:90–101

Afsar B, Umrani WA (2020) Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. Eur J Innov Manag 23(3):402–428

Ahmad F, Karim M (2019) Impacts of knowledge sharing: a review and directions for future research. J Workplace Learn 31(3):207–230

Ahmed T, Khan MS, Thitivesa D, Siraphatthada Y, Phumdara T (2020) Impact of employees engagement and knowledge sharing on organizational performance: Study of HR challenges in COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Syst Manag 39(4):589–601

Akdere M (2009) The role of knowledge management in quality management practices: achieving performance excellence in organizations. Adv Dev Hum Resour 11:349–361

Akram K, Siddiqui S, Nawaz MA, Ghauri T (2011) Role of knowledge management to bring innovation: an integrated approach. Int Bullet Business. Adm 11:121–134

Al Ahbabi S, Singh S, Balasubramanian S, Gaur S (2019) Employee perception of impact of knowledge management processes on public sector performance. J Knowl Manag 23(2):351–373

Al mulhima AF (2020) The effect of tacit knowledge and organizational learning on financial performance in service industry. Manag Sci Lett 10(10):2211–2220

Al Rashdi M, Akmal SB, Al-shami SA (2019) Knowledge management and organizational performance: a research on systematic literature. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng 8(6S4):757–762

Alaaraj S, Mohamed ZA, Ahmad Bustamam U (2016) Mediating role of trust on the effects of knowledge management capabilities on organizational performance. Proc Soc Behav Sci 235:729–738

Alaaraj S, Mohamed ZA, Ahmad Bustamam U (2017) The effect of knowledge management capabilities on performance of companies: a study of service sector. Int J Econ Res 14:457–470

Alavi M, Leidner DE (2001) Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Quart 25(1):107–136

Al-Bahussin S, Elgaraihy W (2013) The impact of human resource management practices, organisational culture, organisational innovation and knowledge management on organisational performance in large saudi organisations: structural equation modeling with conceptual framework. Int J Bus Manag 8(22):1–19

Albassam BA (2019) Building an effective knowledge management system in Saudi Arabia using the principles of good governance. Resour Policy 64:101531

Al-Hakim L, Hassan S (2016) Core requirements of knowledge management implementation, innovation and organizational performance. J Bus Econ Manag 17:109–124

Alhazmi FA (2018) Knowledge management issue: a case study of the department of educational administration at a Saudi University. Int Soc Educ. Plan 25(1):49–60

Alkhazali Z, Aldabbagh I, Abu-Rumman A (2019) Tqm potential moderating role to the relationship between hrm practices, Km strategies and organizational performance: The case of Jordanian banks. Acad Strat Manag J 18(3):1–16

Alnashri AA (2015) Application Reality of Knowledge Management Processes Practice in Leaning Resources Centres: Case Study of Learning Resources Centres in Makkah al-Mukarramah Schools in Saudi Arabia. Procedia Computer Sci 65:192–202

Al-Qarni A, Al-Jayyousi O, Almahamid S (2019) The impact of knowledge management processes on service innovation in international airports in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab Gulf J Sci Res 37(1):1–10

ALSarhani AA (2016) Knowledge management in the public and private sectors organisations-the road to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Al-Rushd Library, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Alsereihy H, Alyoubi A, Emary I (2012) Effectiveness of knowledge management strategies on business organizations in KSA: Critical reviewing study. Middle East J Sci Res 12(2):223–233. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2012.12.2.1690

Alshanty A, Emeagwali O, Ibrahim B, Alrwashdeh M (2019) The effect of market-sensing capability on knowledge creation process and innovation evidence from SMEs in Jordan. Manag Sci Lett 9:727–736