Abstract

This study presents a conceptual model that investigates teaching satisfaction as an outcome variable in mainland China. The model incorporates the mediating mechanism of emotional intelligence and the moderating role of physical activity. The results of a survey of 2500 university teachers from 25 public institutions, which tested teaching satisfaction, demonstrate that job stress is negatively related to teaching satisfaction and indirectly related to emotional intelligence. Physical exercise acts as a moderating factor that alleviates the negative correlation between job stress and emotional intelligence. Overall, our findings indicate that enhancing the frequency of physical exercises can potentially alleviate stress, regulate emotional intelligence, and ultimately contribute to a positive enhancement in teaching satisfaction. These outcomes undeniably hold practical significance for teachers and educational administrators in the realm of higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quality of teaching forms the foundation of the university and is vital for its sustainable development. A crucial metric for assessing the effectiveness of instruction is teaching satisfaction (Truta et al. 2018). It refers to the degree of contented emotional state attained by a person’s evaluation of instructional work and its worth. It reveals how much instructors love their jobs and how they see the state of education today (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2011; Oshagbemi, 2003). Teaching satisfaction is a crucial sign of the effectiveness of talent cultivation and instruction. It is essential for fostering the reform, expansion, and growth of institutions of higher learning (Gao et al. 2021). According to Yin et al. (2013) and Yin (2015), teachers’ emotional intelligence (EI) is a key element in fostering teaching satisfaction. Additionally, a prior study (Biddle and Asare, 2011) found that physical activity enhances self-esteem, self-concept, and self-confidence. Additionally, it promotes communication and empathy while lowering job stress (De Benito and Luján, 2013; Ros et al. 2013).

In the fields of teaching, research, and administration, university faculty members frequently face conflicting expectations (Vardi, 2009). These pressures are sources of work stress for the majority of teachers, which can result in unpleasant feelings and poor professional results like burnout and low job satisfaction (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2007). According to earlier surveys, the situation for university academics in China is significantly worse. Universities and colleges have raised the expectations for teaching and research competitiveness, which has resulted in a high degree of stress, depressive symptoms, emotional exhaustion, and turnover among faculty members at universities (You, 2014; Yin et al. 2020; Han et al. 2021; Yu et al. 2022). A 2013 survey study found that 36% of university faculty members in China suffer from stress (Liu and Zhou, 2016), which has been linked to lower job satisfaction and unfavourable faculty emotions (Gao et al. 2015; Liu and Zhou, 2016; Wang et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2023).

Researchers have recently developed a strong interest in the study of instructors’ emotions. EI is the capacity to perceive, classify, and express emotions accurately. The ability to produce emotions when they are beneficial for thinking, comprehending emotions, and learning about emotions, as well as the capability to control emotions to foster both intellectual and emotional development, are further traits of EI (Mayer and Salovey, 1997). According to previous studies, higher EI scores lead to greater health and well-being (Cabello and Fernández-Berrocal, 2015; Sánchez-Álvarez et al. 2016; Costa et al. 2014) and better job performance (Côté, 2014; Fox and Spector, 2000; Muchhal and Solkhe, 2017). Similar to how perceived stress is frequently described as the type and intensity of negative emotions, pleasant emotions are seen as a critical counterbalance to perceived stress (Rahm and Heise, 2019). Job satisfaction has been proven to be negatively correlated with perceived stress (Klassen and Chiu, 2010). Meanwhile, research has shown that high levels of EI are linked to healthy behaviours like avoiding alcohol and smoking, maintaining a nutritious diet, or engaging in more exercise and are associated with low levels of mental and physical health (Tsaousis and Nikolaou, 2005; Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal, 2002; Lewis et al. 2017).

There has been a significant increase in research related to physical exercise and EI, some from the field of physical education (Ferrer-Caja and Weiss, 2000; García-Martínez et al. 2018; González et al. 2019; Gutiérrez Sas et al. 2017; Lu and Buchanan, 2014; Mouton et al. 2013; Puertas Molero et al. 2017) and others from sport psychology (Bretón Prats et al. 2017; Zurita-Ortega et al. 2017). Emotional changes during physical exercise have been examined in individuals who have undergone physical activity (Duran et al. 2015; Acebes-Sánchez et al. 2019). For instance, physical activity offers the chance to overcome obstacles, work with others as a team, and compete against oneself (Ubago-Jiménez et al. 2019). Experiences with physical activity can act as a mechanism for the development of emotions. Therefore, physical exercise enhances positive emotions (Biddle, 2000), and positive pleasant emotions (Wolfson and Turnbull, 2002; Kerr and Kuk, 2001) and enhances well-being (Szabo, 2003). Most studies have shown a positive correlation between EI and physical exercise levels (Zysberg and Hemmel, 2018; Li et al. 2009; Dev et al. 2012). Thus, those who met exercise recommendations had better EI compared to those who did not meet the exercise recommendations (Li et al. 2009; Dev et al. 2012). In a similar vein, there were notable differences in EI between physically active and inactive people; the active people had better EI (Fernández Ozcorta et al. 2015). Other studies (Tsaousis and Nikolaou, 2005; Saklofske et al. 2007; Magnini et al. 2011; Li et al. 2011) have demonstrated a substantial relationship between EI and the amount of exercise.

The majority of recent research on teachers’ stress has used faculty samples from Western universities. However, given the cross-national cultural differences associated with stress interpretation and coping, it is questionable to what extent these findings are applicable to the Chinese higher education context (Shin and Jung, 2014). Few researchers have examined whether job stress and EI are associated with the level of physical exercises that faculty do to enhance teaching satisfaction. The purpose of our study was to explore the direct relationship between job stress and teaching satisfaction and to attempt to understand how EI and physical exercise work together to influence teaching satisfaction and thus help university faculty feel satisfied with their teaching jobs.

Literature review

Job stress and teaching satisfaction

Faculty satisfaction in teaching is significantly influenced by job stress. Numerous contextual factors, such as an increased workload, a lack of free time, problems with student behaviour, a lack of adequate resources, a lack of administrative support, and the variety of tasks needed are frequently predictors of teacher job stress (Kokkinos, 2007; Berryhill et al. 2009; Fütterer et al. 2022). These elements may lower job satisfaction (Armstrong et al. 2015), lower teaching self-efficacy (Klassen et al. 2013), job burnout (Wang et al. 2020), and lower EI (Petrides et al. 2016) as well as lower educational quality.

In Chinese higher education, there have been few studies that specifically analyze the relationship between faculty job stress and job satisfaction, but it is well known that job stress is a major contributor to dedication, presentation, and faculty turnover, all of which are strongly correlated with job happiness (Toropova et al. 2021; Bogler and Nir, 2015; Dorenkamp and Ruhle, 2019; Riyadi, 2015). Academic and teaching job stress has increased in colleges and universities as a result of the changing working conditions and environment in higher education, including increased levels of management control, increased job demands, and job insecurity (Kinman and Jones, 2008; Ablanedo-Rosas et al. 2011; Shin and Jung, 2014). In addition, studies have shown that teacher self-efficacy is a strong predictor of teachers’ effective implementation of instructional strategies (Künsting et al. 2016), and Gentile et al. (2023) argued that teachers with low self-efficacy also have a greater negative impact on the implementation of instructional strategies and teaching performance. Even faculty members who are happy with their jobs can experience extremely high levels of job stress. Tian and Lu (2017) found that the rapid expansion of China’s shift to mass education and the demanding requirements to improve international rankings and competitiveness, as well as higher demands on research productivity and funding, resulted in greater teaching workload pressures on faculty and staff. Because of this, faculty members are being forced to handle heavier responsibilities in terms of teaching and research, which increases workplace stress (Jacobs and Winslow, 2004; Tytherleigh et al. 2005; Houston et al. 2006; Dickson-Swift et al. 2009).

High job stress is also a problem for Chinese university professors (Li and Kou, 2018; Han et al. 2021), and it is linked to lower job satisfaction (He and Liu, 2012; Gao et al. 2015; He, 2015). For university teachers, the strain and weight of a large workload are more likely to diminish the value of their work experience, encourage negative feelings, and reduce job satisfaction (Zang et al. 2022). University lecturers with more stressful occupations have been found to have higher rates of burnout (Li, 2018). Job stress was shown to be negatively correlated with job satisfaction but mitigated the negative association between job stress and organisational commitment, according to a recent study of 1906 university instructors in China (Wang et al. 2020). Previous studies on the job satisfaction of university professors have discovered a significant correlation between job stress and job satisfaction in various groups. As a result, the first hypothesis of this study is that teaching pleasure is adversely correlated with the job stress of university professors.

Emotional intelligence and teaching work

EI refers to the ability to express and evaluate one’s own and others’ emotions, control one’s own and other’s emotions, and use emotions to resolve practical issues. It is the comprehensive ability to accurately perceive, express, and evaluate emotions (Mayer and Salovey, 1997). According to previous studies, Salovey and Mayer (1990) stated that EI can be viewed as “a subset of social intelligence that includes the ability to monitor one’s own and other’s feelings and emotions, distinguish between them, and use this information to guide ones’ thinking and actions” (p. 189). EI includes abilities including awareness of oneself, compassion, handling emotions, self-motivation, and managing connections with others, according to Goleman (1995).

The two different EI models that are now accessible are the ability model and the trait model. EI is the ability to understand, use, and regulate one’s own and other people’s emotions. Two maximum performance tests can be used to measure EI: the Multifactor Intelligence Scale (MEIS; Mayer and Salovey, 1997) and the Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Scale (MSCEIS; Mayer et al. 2004). EI is classified at a lower level of personality taxonomies and is viewed in the trait model as a constellation of emotion-related self-perceptions and behavioural dispositions that affect peoples’ capacity to perceive and exploit emotion-related information (Shi and Wang, 2007). Two self-report measures that are frequently used in studies to measure EI are the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS; Wong and Law, 2002) and the Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS; Schutte et al. 1998).

In the context of higher education, some academics have accepted the characteristic model. When using the EIS developed by Schutte et al. (1998), Chan (2004, 2006) suggested that teachers’ EI has four dimensions: emotional assessment, positive regulation, empathy sensitivity, and positive utilisation. Some researchers have suggested that teachers’ EI includes four different dimensions: self-evaluation of emotions, evaluation or recognition of others’ emotions, regulation of self-emotions, and use of emotions to facilitate performance (Wong et al. 2010; Karim and Weisz, 2011). Additionally, Petrides (2009) developed the TEIQe-SF (short form), which consists of 30 items measuring four broad factors (well-being, self-control, emotionality, and sociability) and global trait EI that is directly entered into the TEIQue-SF total score. The TEIQue-SF focuses on emotion-related self-perceptions as measured by self-report questionnaires. The higher-order structure of the TEIQue-SF is assumed to be oblique, making it a multifaceted construct (Petrides and Mavroveli, 2018). This study synthesises this plethora of knowledge by focusing on the EI model and using a self-report questionnaire to assess teachers’ EI.

Ignat and Clipa (2012) argued that teachers’ EI plays a key role in the expression of their positive attitudes and satisfaction with their work and life, which contributes to their effectiveness as a teacher. Similarly, EI is an important component of positive psychology that has a significant impact on human performance, well-being, and subjective well-being (Bar-On, 2010). However, current research on the relationship between EI and teacher burnout or work-related stress, which explores the relevance of trait EI to teachers’ teaching jobs, has yielded inconsistent findings. For instance, Zeidner et al. (2012) proposed that EI has an effect on reducing occupational stress, decreasing negative emotion levels, and experiencing positive emotional states. In addition, a meta-analytic review that correlated EI with health, well-being, and performance indicators revealed differences in self-reported and performance EI tests (Miao et al. 2016; Sánchez-Álvarez et al. 2015). However, these cumulative findings suggest that different conceptualisations of EI and specific emotional skills, as measured by different EI tests, are associated with lower burnout or higher teaching satisfaction symptoms. In fact, it is not understood how different EI types impact burnout symptoms in different ways. Based on ability and trait models, a number of instruments have been created that include several aspects (Mayer et al. 2008). Therefore, it is challenging to synthesize the present understanding of research in this domain due to the variability of measures.

Physical exercise, job stress, and emotional intelligence

Physical exercise is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle that results in energy expenditure in excess of resting energy expenditure” (Thompson, 2003). Physical exercise is associated with physical (Kokkinos, 2008; Chomistek et al. 2013; Archer and Blair, 2011; Hamilton et al. 2007; Cavill et al. 2006), psychological, and social wellness (Penedo and Dahn, 2005; Biddle and Asare, 2011; Paluska and Schwenk, 2000; Mammen and Faulkner, 2013; Ströhle, 2009; Hills et al. 2015). In the particular context of mental health, earlier research has discovered that people who exercise physically exhibit improved psychological well-being and experience less stress and despair. These results applied to young people (Norris et al. 1992; Brand et al. 2017), college students (Castillo and Molina-García, 2010; Molina-García et al. 2011), and the elderly (Netz et al. 2005; Gogulla et al. 2012). Human physiology benefits from physical activity in a number of ways. Its value in preventing obesity, cardiovascular disease, and high blood pressure has been shown in some trials (Okay et al. 2009). Exercisers may have decreased rates of depression, according to Strawbridge et al. (2002) study. Additionally, those who exercised were more likely to partake in other healthy and beneficial pursuits. This study also looked at the causal link between physical activity and depression and came to the conclusion that there was none. Increased exercise and decreased job stress were found to have a real association but not a causal relationship. Early studies (Lawlor and Hopker, 2001; Sjösten and Kivelä, 2006; Stathopoulou et al. 2006) revealed that physical activity as an intervention has clinical consequences for the treatment of depression. Moreover, it has been asserted (Wickramasinghe, 2010) that physical activity is a form of personal coping that not only lessens stress (Clark et al. 2016; Nguyen-Michel et al. 2006) but also guards against its negative effects (Fang et al. 2019; Moreira-Silva et al. 2014; Toker and Biron, 2012). Adults should engage in at least 75 min of vigorous aerobic exercise (VPE), at least 150 min of moderate aerobic exercise (MPE), or an equivalent combination of both, every week, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) (World Health Organization T, 2010).

Over the past few decades, a number of theories have been put up to explain how regular physical activity participation influences employees’ psychological functioning in terms of work-related outcomes (Naczenski et al. 2017). According to empirical research on physiological mechanisms, regular physical activity can help reduce workplace psychological stress (Klaperski et al. 2014). Regarding the cross-stressor adaptation hypothesis mechanism, regular physical activity causes biological adaptations (such as altering individual sedation patterns, lowering blood pressure, and reducing hormone production) that lessen physiological reactions to stressors in general, including job stressors, as well as to stressors specific to physical exercise (Klaperski et al. 2013; Sothman, 2006; Zhao et al. 2021). Given that empirical research has demonstrated that quick recovery from stress can avoid many health-related issues, adaptability across stressors through physical activity is regarded as a key health-protective strategy (Chrousos, 2009). Additionally, a number of research on the mechanisms for recovering from job stress (such as Feuerhahn et al. 2014; Sonnentag et al. 2017) have noted the importance of physical exercise outside of work for reducing job stress, refilling depleted resources, and increasing levels of work engagement.

According to the studies consulted, people appreciate how the practice of physical activity and sport provides much satisfaction in exchange for much effort. Physical exercise involves relaxation, provides an opportunity to face challenges, and is a way to work together and motivate as a team, or to compete with oneself (Castro-Sánchez et al. 2018; Castro-Sánchez et al. 2018). IE and physical exercise are strongly related to the extent that many relaxation, concentration, and visualisation techniques are being shared in more and more clubs, and federations, and even coaches are hiring more professionals to implement these techniques with the aim of improving athletes’ performance (Puertas-Molero et al. 2018). Similarly, it emphasises the importance of physical exercise practices in producing improvements in physical, psychological, and social aspects, as well as the quality of life reflected (González Valero et al. 2017). However, the use of physical exercise to regulate faculty emotions in higher education is insufficiently studied.

People who engage in physical exercise experience emotional changes during the practice (Zamorano-García et al. 2018; Romero-Martín et al. 2017). Some scholars have pointed out that physical exercises are strongly associated with EI, and the emotional characteristics of individuals become more obvious after physical exercises. People who consciously and consistently exercise for a long period of time are generally less likely to have emotional problems such as anxiety, fright, and social disorders (Downs and Strachan, 2013; Ubago-Jiménez et al. 2019). In modern countries, the lack of physical exercise may have a negative impact on physical health and psychological well-being (Erikssen, 2001; Gutin et al. 2007; Rexrode et al. 1998; Blaes et al. 2011). Physical exercise is linked to better stress management and increased levels of EI, which are crucial for human interaction in daily life (Gacek and Frączek, 2005; Bhochhibhoya et al. 2014; Roxana Dev et al. 2014).

The current study

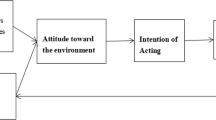

A review of the literature found that there is still little empirical data on the connections between job stress, teachers’ EI, physical exercise, and teaching satisfaction. Therefore, this study attempts to examine the effects of teachers’ job stress, EI, and physical exercises on teaching satisfaction using a sample of university teachers from China (Fig. 1). Specifically, this study aims to answer the following five research hypotheses:

H1. Teachers’ job stress is negatively related to teaching satisfaction.

H2. Teachers’ job stress is negatively related to teachers’ EI.

H3. Teachers’ EI predicts and positively influences teaching satisfaction.

H4. Teachers’ EI would undermine the negative relationship between job stress and teaching satisfaction.

H5. The mediating effect of EI will differ by the frequency of physical exercises.

Methodology

Participants and data collection

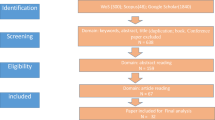

The study utilized a quantitative survey design that encompassed higher education institutions (HEIs) in Sichuan Province, China. A voluntary, anonymous online poll was conducted with 2680 university teachers from 25 public universities in Sichuan, western China. The university teachers are from different disciplines: math education, international economics and trade, accounting, financial management, business management, and statistics. The poll was carried out using a convenience sample approach as part of a university teacher training programme that the Sichuan Provincial Department of Education launched in July 2023.

Before data collection, we obtained approval from the Academic Board of the Faculty of Education and Psychology of the authors’ university. Afterwards, the research team sent a consent letter to each teacher. In the letter, we specified our confidentiality protection code, the pure nature of the volunteers’ participation, as well as the secure storage of the data and access restrictions. Moreover, the university professors had to respond to all of the questions.

Data collection consisted of four questionnaires (i.e., job stress, emotional intelligence, physical exercise, and teaching satisfaction). The questionnaires were administered online, so teachers were free to decide when and where they would participate. In addition, all research participants were informed about the research objectives of the study and were given the same instructions. Finally, anonymity was guaranteed in all steps of data processing. Exclusion criteria for participation in the study included refusal to provide informed consent, unwillingness to continue with the study, multiple completion of questionnaires by the same participant, and incomplete questionnaires. A total of 92 questionnaires were excluded due to incompleteness, 25 questionnaires were removed as they represented multiple responses from the same participant, and 63 samples were discarded during the data cleaning process. As a result, a final dataset of 2500 questionnaires was retained, yielding a response rate of approximately 93.3%.

Instruments

Four different scales were used in this study to measure job stress, teachers’ EI, physical exercise, and teaching satisfaction. The questionnaire was based on a set of four standardised scales and a set of demographic questions.

Job stress

The College Work Stress Scale (CWSS: Li, 2005) was employed in this study to gauge employee stress. The CWSS, which consists of 24 items and is scored on a Likert scale from 1 (no stress) to 5 (severe stress), is intended to measure the level of job stress among university staff. “Please assess these factors as a source of stress for you: a chance for promotion”, read one sample question. The scale took into account five factors that affect work stress, including job stability, academic tenure, social connections, work pressure, and work enjoyment. The CWSS exhibited strong internal consistency reliability (=0.92) for all items, according to Lis’ 2005 study. The CWSS has sufficient internal consistency reliability (=0.81 to 0.91) and construct validity evidence in Chinese studies, according to a number of earlier investigations (He and Liu, 2012; Ni et al. 2016; Wang and Jing, 2019). Employment security (1 item), interpersonal relationships (3 items), and work enjoyment (2 items) were the three employment stresses considered in this study.

Emotional intelligence

The Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS) measures a person’s capacity for emotional expression, self-regulation, and problem-solving. The Wang (2002) revised Chinese version of the scale was applied in this investigation. The measure has 33 items total, of which 5, 28, and 33 are quantified using a 5-point Likert scale and are reverse-scored. They were scored on a scale of 1–5 based on the “very inconsistent-very consistent” option, with scores ranging from 33–165, and higher scores indicating stronger EI. The final three dimensions of EI used in this study are self-emotion appraisal (4 items), use of emotions (4 items), and regulation of emotions (4 items) (Wong and Law, 2002).

Physical exercise

Physical exercise was the moderating variable in this study, and the item measured was “In the past 12 months, how many times per week did you typically engage in up to 30 min of physical activity that made you sweat?” It was developed as an enhancement to the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which has been validated and used to evaluate physical exercise patterns (Craig et al. 2003). This is a continuous variable with a maximum value of 7, a minimum value of 1, and a mean value of 4.36.

Teaching satisfaction

A specific aspect of faculty satisfaction with the teaching profession as a whole was evaluated using the 5-item Teaching Satisfaction Scale (TSS), which was created by Ho and Au (2006). A 5-point scale (1 being entirely disagreed, and 5 being completely agreed) was used for all five questions.

Demographics

Gender, professional rank (professors and associate professors, lecturers and teaching assistants), and type of higher education institution (national research-oriented universities and provincial teaching-oriented universities) were the three primary demographic indicators that were collected for this study. The items in all four scales used in this research were originally developed in English and later translated into Chinese. To ensure linguistic equivalence, a translation and back-translation procedure was employed. This process helped in achieving consistency and accuracy in the Chinese translations of the scale items.

Data analysis strategy

The discrepancies between participants’ responses were examined during the data filtering procedure. If participants responded the same to each question, cases were eliminated. Using the expectation maximisation (EM) method, it was calculated that less than 5% of the data were missing. Three stages made up the analysis plan for this investigation. First, the scales’ validity and reliability were examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the internal consistency (Cronbachs’ alpha) coefficient. Second, the link between the bivariate variables was examined using Pearson correlation analysis and linear regression analysis. The levels of significance were set at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001. Thirdly, using Mplus 8.0, a comprehensive structural equation model (SEM) was built based on a mediation analysis of bootstrap techniques to ascertain the connection between job stress, EI, and teaching satisfaction among university professors in a higher education context. A variety of acceptable metrics, such as RMSEA < 0.08, SRMR < 0.05, CFI > 0.9, and TLI > 0.9, were used to assess the model fit (Schreiber et al. 2006). The bootstrap method was utilized in mediation analysis to find unintended consequences (Hayes, 2009).

Results

Reliability and CFA analysis of the scales

This analysis’s first phase involved applying CFA to examine each standardised measure’s factor structure. Each scale’s reliability and CFA analyses were evaluated in various educational settings. The findings show that each scale’s reliability coefficients, with Cronbachs’ alpha values ranging from 0.785 to 0.892, were satisfactory.

Table 1 presents a summary of the CFA findings. The CFA assessment of SEA, OEA, UOE, and ROE revealed a well-fitting model (χ2 = 418.744, df = 100, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.987, TLI = 0.984, SRMR = 0.021). Similarly, the CFA analysis of JS demonstrated a good model fit (χ2 = 546.656, df = 202, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.026, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.988, SRMR = 0.017). As for PE, the CFA analysis indicated an appropriate model fit (p < 0.001, CFI = 1, TLI = 1). The results of the CFA analysis suggest that TS (χ2 = 57.442, df = 5, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.065, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.984, SRMR = 0.013) was a good fit for the data.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The participants of this study were 2500 university teachers, in terms of gender, 1120 were male teachers (44.8%) and 1380 were female teachers (55.2%); in terms of position, 500 were professors (20%); 850 were associate professors (34%); 1000 were lecturers (40%); and 150 were teaching assistants (6%); in terms of experience, 230 were university teachers with 1–2 years (9.2%); 520 were university teachers with 3–5 years (20.8%); 850 were university teachers with 6–10 years (34%); and 900 were university teachers with 10 years and above (36%). In terms of experience, there were 230 university teachers with 1–2 years (9.2%); 520 university teachers with 3–5 years (20.8%); 850 university teachers with 6–10 years (34%); and 900 university teachers with 10 years and above (36%).

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for each of the latent variables in the sample of university teachers. The results show that job stress was significantly and negatively related to emotional intelligence (r = −0.494, p < 0.01), teaching satisfaction (r = −0.618, p < 0.01), and physical exercise (r = −0.061, p < 0.01). However, emotional intelligence was found to be significantly and positively related to teaching satisfaction (r = 0.592, p < 0.01) and physical exercise (r = 0.097, p < 0.01). Finally, teaching satisfaction was significantly and positively associated with physical exercise (r = 0.123, p < 0.01).

Structural Model

The model fit indicators show that the structural model had a good fit to the data (χ2 = 1566.41, df = 846, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.018, CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.988, SRMR = 0.017). As can be seen from Table 3, there is a statistically significant relationship between teacher job stress and emotional intelligence (β = −0.551, p < 0.001). However, emotional intelligence significantly and positively predicts teaching satisfaction (β = 0.418, p < 0.001). At the same time, there is a significant negative association between teacher job stress and teaching satisfaction (β = −0.454, p < 0.001).

Mediation effect of emotional intelligence

The bootstrap method was used to test the significance of the mediating path. That is, whether the indirect effect of teacher job stress on teaching satisfaction through teacher emotional intelligence was significantly different from zero. The path analysis was conducted using Mplus 8.0 for this purpose. The results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3 shows that the indirect effect of teachers’ job stress on teaching satisfaction through emotional intelligence is significant (β = −0.230, p < 0.001), and the 95% C.I. is [−0.259, −0.209]. According to the results reported in Table 3, we can see that H1, H2, H3, and H4 are all supported.

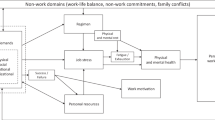

Testing of moderated mediation models

For testing the moderating effect of physical exercise, we used hierarchical regression analyses in this study. As presented in Table 4, this study used PROCESS model 7 to test the relationship between the interaction of physical exercise and job stress on emotional intelligence. The results show that the interaction between job stress and physical exercise was significant (b = 0.265, t = 18.609, p < 0.001), and physical exercise was able to positively moderate the effect of job stress on emotional intelligence. Furthermore, we conducted simple slope analyses (Aiken et al. 1991) to analyse the mediating role of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and teaching satisfaction at low (one SD below the mean) and high (one SD above the mean) levels of physical exercise. The results (see Fig. 2) show that job stress was significantly negatively correlated with emotional intelligence under the moderating effect of high and low group physical exercise (b = −0.188, t = −7.743, p < 0.001; b = −0.827, t = −34.433, p < 0.001). It can be seen that the level of negative correlation between job stress and emotional intelligence is somewhat stronger under the moderating effect of the low-group physical exercise.

In addition, this study also adopted Bootstrap (5000 times) results (see Table 4) and show that the difference in the mediation effect sizes between the low and high values of physical exercise was 0.274, and the 95% confidence intervals [0.239, 0.311] did not contain 0. The difference in effect sizes was significant, and physical exercise can positively moderate the mediating effect of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and teaching satisfaction. This result supports the H5.

Discussion

This study’s objective was to give theoretical and empirical knowledge about the evolution of university professors’ mental health within the setting of Chinese higher education. This study focuses on the direct effects of job stress on university teachers’ satisfaction with their instruction, the mediating effect of TEI on job stress and teaching satisfaction, and the mechanisms by which physical exercise modifies the relationship between teachers’ job stress and EI. This is a crucial step in developing teachers’ mental health and in comprehending the mechanisms that underlie them. The association between teachers’ job stress, emotional intelligence, physical exercise, and teaching satisfaction is supported by our findings.

Five hypotheses were tested using a higher-order model in SEM to provide support for our investigation. This study hypothesizes that teachers’ job stress is negatively related to teaching satisfaction (H1). These associations help us understand the negative findings while providing opportunities to reformulate our theory of faculty stress in the Chinese context. University faculty members almost always encounter pressures connected to their jobs, and a significant amount of study has been done to investigate this topic. Stress has been highlighted as an important component in the newly emerging literature on faculty development in China, serving as both a significant independent and dependent variable. Meng and Wang (2018), for instance, show that the stress levels of Chinese teachers varied according to their professional status, age, and amount of teaching time. They also stress the significance of understanding “the positive effects of occupational stress while working to eliminate stressors” (p. 603). Jing (2008) looked at workplace stress among undergraduate professors and discovered that it had a substantial impact on how well they were able to teach, which is why she encouraged “administrators and faculty to manage their stress and stimulus performance” (p. 294). According to Sun et al. (2011), China’s university teachers are particularly vulnerable to professional stress due to poor mental health. They came to the conclusion that one of the key steps in lowering occupational stress is to improve mental health and the organisational climate. These and other findings, such as Lai et al. (2014) and Tian and Lu (2017), have elevated the role of stressors in both theory and related research. Our study challenges this notion. More precisely, stress plays a significant role in this area of research, but by using stress assessment as the foundation for validity, we can better comprehend the patterns and mechanisms connected to teaching satisfaction.

This study also predicts a negative relationship between teachers’ job stress and EI, thus supporting the study’s H2. The effect size of teachers’ job stress on EI was −0.551, indicating that job stress plays a promising role in predicting EI and outcomes (Zysberg et al. 2017; Asrar-ul-Haq et al. 2017; Naseem, 2018). The findings of the study confirm those reported in previous studies involving teachers in higher education settings, emphasizing that teachers’ job stress is a critical factor influencing TEI (Akomolafe and Ogunmakin, 2014; Yusoff et al. 2013; Usmani et al. 2022). At the higher education level, fewer studies have been conducted on the importance of teachers’ teaching satisfaction, and these studies have addressed teachers’ teaching styles, cultural backgrounds, and perceptions. The association between occupational stress and EI among faculty members in different fields in higher education institutions, however, does not appear to have been extensively examined in prior studies. The findings of this study stress the significance of this link for present and future faculty members and researchers in higher education institutions.

The study’s findings are consistent with the premise that there is a strong positive relationship between teachers’ feelings of job satisfaction and their EI. According to earlier studies (Khassawneh et al. 2022; Yin et al. 2013; Efendi et al. 2021), EI is a critical component of success as a teacher. The effects of EI on reducing occupational stress, reducing negative emotions, and promoting positive emotional states have been demonstrated in numerous studies (Keefer et al. 2009; Zeidner et al. 2012). Numerous research (Keefer et al. 2009; Zeidner et al., 2012) have shown that EI has a favourable impact on reducing occupational stress, reducing negative emotions, and boosting positive emotional states. Given this data, it is becoming more widely accepted that raising teachers’ well-being and enhancing their stress resilience can both benefit from EI training (Vesely-Maillefer and Saklofske, 2018). To measure teachers’ emotional intelligence, this study used three substructures: self-emotional appraisal, use of emotions, and management of emotions. The findings show a considerable correlation between EI and teaching satisfaction, with an EI-teaching satisfaction correlation coefficient of 0.592 being statistically significant. This implies that teachers’ levels of happiness at work are significantly influenced by their EI. Teachers who have high EI are more likely to believe in their ability to do their jobs well and to be open to taking on difficult teaching tasks that might result in effective performance.

The results of this study support hypothesis H4, which claims that instructors’ emotional intelligence (EI) is a critical mediator between job stress and teaching satisfaction. This supports the EI theory stated by Mayer et al. (1999). To the best of our knowledge, no prior research has examined how EI in teachers may play a mediating role in the link between job stress and teaching satisfaction. However, earlier studies have demonstrated that EI is a key mediator in the relationship between various teacher attributes in primary and secondary schools (Yin et al. 2016; Ju et al. 2015; Vesely et al. 2013; Berkovich and Eyal, 2017; Basim et al. 2013; Mérida-López et al. 2017; Latif et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2023). Therefore, the findings of this study are well supported, and the mediating role of teachers’ EI between job stress and teaching satisfaction is reasonable.

Higher EI makes university faculty members more demanding in the higher education context. They have the capacity to put in the necessary effort to accomplish professional objectives including engaging in demanding instruction, producing works of high calibre, and submitting grant applications. Faculty members may be able to develop EI from these triumphs, allowing them to remain satisfied with their teaching even while under pressure.

In our mediation model, physical exercise was found to be significantly associated with EI as an external contextual variable. Our findings suggest that the mediating effect of EI is not dependent on physical exercise, as the mediating effect continues to work regardless of university faculty members’ frequency of physical exercise (i.e. the non-significant result of moderated mediation). However, the significant moderating effect of physical exercise suggests that teachers who engage in more frequent physical activity may have higher EI, which may positively impact their perceptions of job stress and job satisfaction. This result supports the well-established idea that physical exercise is an important source of teachers’ perceived evaluations of their own EI.

Furthermore, our results support earlier studies showing that instructors who exercise more frequently had higher emotional quotients (Gacek and Frączek, 2005; Bhochhibhoya et al. 2014; Roxana Dev et al. 2014; Ubago-Jiménez et al. 2019). Salovey and Mayers’ (1990) hypothesis supports the idea that EI is made up of three distinct adaptive skills: emotion appraisal and expression, emotion regulation, and emotion utilisation in problem-solving. By controlling their negative emotions and focusing on their positive and pleasurable feelings, teachers can modify their emotions and lessen their work stress through physical exercise. This can lead to improved EI, better well-being, and less stress and depression.

Moreover, teachers who persist in physical exercise may have faced many challenging tasks and eventually found effective ways to cope with stressful situations. As a result, they can draw on their experiences of solving job stress problems to improve their emotional state and believe in their ability to accomplish any teaching task. When teachers have high levels of positive emotions, they are more likely to control their stress levels and cope effectively with challenging teaching tasks.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of the study restricts our ability to make causal inferences about the results. A longitudinal design would provide greater certainty in investigating and highlighting significant variation and development among the study variables over time. Secondly, the moderating effects of demographic factors such as age, gender, teaching experience, and highest education could have been better understood in relation to the focus of the study. Thirdly, the method of measurement of the study variables is also a limitation. Although it is more economically feasible to assess physical exercise (PE) with self-report instruments, similar scales need to be validated in different countries. Objective assessment of physical exercise using pedometers and accelerometers may be a more accurate tool that avoids the overestimation of physical exercise that often occurs with questionnaires (Haskell, 2012; Warren et al. 2010). Fourthly, our measures were derived exclusively from teachers’ self-reports, which can sometimes lack reliability and be subject to reporting bias. In addition, there may be some potential limitations to self-reported data for reasons such as social expectations and desirability. Finally, EI is also measured using self-report instruments. If EI is assessed as a set of competencies or skills (Mayer et al. 1999), it can be measured with maximum validity.

Conclusion

The present study provides an important contribution to the existing knowledge base by establishing a direct link between university faculty job stress and teaching satisfaction and EI, and between EI and teaching satisfaction. Moreover, the study highlights the moderating role of physical exercise between job stress and EI and the mediating role of EI between job stress and teaching satisfaction. These results successfully support all research hypotheses and provide considerable support for important theoretical propositions. However, it is essential to note that teachers’ job stress and EI were equally important in influencing teaching satisfaction, and mediated the relationship between job stress and EI. The theoretical framework of this study contributes to the theoretical research in both the field of EI theory and social cognitive theory.

Furthermore, in contrast to universities with a focus on research in Western nations, faculty development programmes are extremely rare in China. However, given the formation of the China Education Project, our findings imply that we should apply psycho-cognitive and behavioural concepts to reduce the negative effects of occupational stress. Practical strategies for assessing health in specific situations and developing coping strategies to deal with potential stress may help individual teachers to reduce stress.

The stress of change in teaching and learning is a major concern as it has the potential to reduce teachers’ sense of efficacy in teaching and increase their engagement and satisfaction with teaching. Enabling teachers to enjoy the process of dealing with changes in the teaching environment can have a positive impact on promoting their positive attitudes towards teaching. Therefore, to maximise the good effects of the changes in teaching, it is important to provide teachers with the practical aid and guidance they need to manage their perceived stress.

Finally, our findings highlight the need to improve teachers’ perceptions of their own teaching efficacy in order to enhance their performance as teachers and raise their engagement and happiness with the profession. In order to address the actual demands at the individual and administrative levels, teacher development programmes may want to rethink and reevaluate the design and content of teacher training programmes.

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are available at https://osf.io/zeuhj.

References

Ablanedo-Rosas JH, Blevins RC, Gao H, Teng WY, White J (2011) The impact of occupational stress on academic and administrative staff, and on students: An empirical case analysis. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 33(5):553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X2011605255

Acebes-Sánchez J, Diez-Vega I, Esteban-Gonzalo S, Rodriguez-Romo G (2019) Physical activity and emotional intelligence among undergraduate students: A correlational study. BMC Public Health 19(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7576-5

Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage

Akomolafe MJ, Ogunmakin AO (2014) Job satisfaction among secondary school teachers: Emotional intelligence, occupational stress and self-efficacy as predictors. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 4(3):487. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr2014v4n3p487

Archer E, Blair SN (2011) Physical activity and the prevention of cardiovascular disease: From evolution to epidemiology. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 53(6):387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpcad201102006

Armstrong GS, Atkin-Plunk CA, Wells J (2015) The relationship between work-family conflict, correctional officer job stress, and job satisfaction. Crim. Just. Behav. 42(10):1066–1082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815582221

Asrar-ul-Haq M, Anwar S, Hassan M (2017) Impact of emotional intelligence on teacher׳ s performance in higher education institutions of Pakistan. Future Bus. J. 3(2):87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/jfbj201705003

Bar-On R (2010) Emotional intelligence: an integral part of positive psychology. South Afr. J. Psychol. 40(1):54–62. https://hdlhandlenet/10520/EJC98569

Basim HN, Begenirbas M, Can Yalcin R (2013) Effects of teacher personalities on emotional exhaustion: mediating role of emotional labor. Educ. Sci.: Theory Pract. 13(3):1488–1496

Berkovich I, Eyal O (2017) Emotional reframing as a mediator of the relationships between transformational school leadership and teachers’ motivation and commitment. J. Educ. Adm. 55(5):450–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-07-2016-0072

Berryhill J, Linney JA, Fromewick J (2009) The effects of education accountability on teachers: are policies too-stress provoking for their own good? Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 4(5):1–14

Bhochhibhoya A, Branscum P, Taylor EL, Hofford C (2014) Exploring the relationships of physical activity, emotional intelligence, and mental health among college students. Am. J. Health Stud. 29(2). https://doi.org/10.47779/ajhs2014215

Biddle SJ, Asare M (2011) Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 45(11):886–895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185

Biddle S (2000) Exercise, emotions, and mental health. Champaign: Hum. Kinet., 92–267

Blaes A, Baquet G, Fabre C, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S (2011) Is there any relationship between physical activity level and patterns, and physical performance in children? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-122

Brand S, Kalak N, Gerber M, Clough PJ, Lemola S, Sadeghi Bahmani D, Holsboer-Trachsler E (2017) During early to mid adolescence, moderate to vigorous physical activity is associated with restoring sleep, psychological functioning, mental toughness and male gender. J. Sports Sci. 35(5):426–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041420161167936

Bretón Prats S, Zurita Ortega F, Cepero González MDM (2017) Análisis de los constructos de autoconcepto y resiliencia, en jugadoras de baloncesto de categoría. Cadete 26(1):127–132. http://hdlHandle.net/10481/50305

Bogler R, Nir AE (2015) The contribution of perceived fit between job demands and abilities to teachers’ commitment and job satisfaction. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 43(4):541–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214535736

Cabello R, Fernández-Berrocal P (2015) Implicit theories and ability emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 6:700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg201500700

Castillo I, Molina-García J (2010) Adiposidad corporal y bienestar psicológico: efectos de la actividad física en universitarios de Valencia España. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 26(4):334–340

Castro-Sánchez M, Chacón-Cuberos R, Ubago-Jiménez JL, Zafra-Santos E, Zurita-Ortega F (2018) An explanatory model for the relationship between motivation in sport, victimization, and video game use in schoolchildren. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15(9):1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091866

Castro-Sánchez, M, Chacón-Cuberos, R, Zurita-Ortega, F, Puertas-Molero, P, Sánchez-Zafra, M, Ramírez-Granizo, I (2018) Emotional intelligence and motivation in athletes of different modalities 13(2), S162-S177. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse201813Proc201

Cavill N, Kahlmeier S, Racioppi F (Eds) (2006) Physical activity and health in Europe: evidence for action. WHO Regional Office Europe

Chan DW (2004) Perceived emotional intelligence and self-effificacy among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Personal. Individ. Differ. 36(8):1781–1795. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpaid200307007

Chan DW (2006) Emotional intelligence and components of burnout among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Teach. Teach. Educ. 22(8):1042–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/jtate200604005

Clark MM, Jenkins SM, Hagen PT, Riley BA, Eriksen CA, Heath AL, Douglas KSV, Werneburg BL, Lopez-Jimenez F, Sood A, Benzo RP, Olsen KD (2016) High stress and negative health behaviors: a five-year wellness center member cohort study. J Occup Environ Med 58(9):868–873. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000826

Costa S, Petrides KV, Tillmann T (2014) Trait emotional intelligence and inflammatory diseases. Psychol., Health Med. 19(2):180–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/135485062013802356

Côté S (2014) Emotional intelligence in organizations. Annu Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 1(1):459–488. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091233

Chomistek AK, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Lu B, Sands-Lincoln M, Going SB, Eaton CB (2013) Relationship of sedentary behavior and physical activity to incident cardiovascular disease: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61(23):2346–2354. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjacc201303031

Chrousos GP (2009) Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 5(7):374–381. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo2009106

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Oja P (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35(8):1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01MSS000007892461453FB

De Benito MM, Luján JIG (2013) Inteligencia emocional, motivación autodeterminada y satisfacción de necesidades básicas en el deporte. Cuad. de. Psicol.ía del. Deporte 12(2):39–44

Dev RDO, Ismail IA, Omar-Fauzee MS, Abdullah MC, Geok SK (2012) Emotional intelligence as a potential underlying mechanism for physical activity among Malaysian adults. Am. J. Health Sci. 3(3):211–222. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajhsv3i37140

Dickson‐Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Talbot L, Verrinder G, Ward B (2009) A non‐residential alternative to off campus writers’ retreats for academics. J. Furth. High. Educ. 33(3):229–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770903026156

Dorenkamp I, Ruhle S (2019) Work–life conflict, professional commitment, and job satisfaction among academics. J. High. Educ. 90(1):56–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022154620181484644

Downs MC, Strachan L (2013) High school sport participation: Does it have an impact on physical activity participation and self-efficacy? J. Exerc., Mov., Sport (SCAPPS Referee. Abstr. Repos.) 45(1):101–101

Duran C, Lavega P, Salas C, Tamarit M, Invernó J (2015) Educación Física emocional en adolescentes Identificación de variables predictivas de la vivencia emocional(Emotional Physical Education in adolescents Identifying predictors of emotional experience). Cult., Cienc. Y. Deporte 10(28):5–18. https://doi.org/10.12800/ccdv10i28511

Efendi E, Harini S, Simatupang S, Silalahi M, Sudirman A (2021) Can job satisfaction mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence on teacher performance? J. Educ. Res. Eval. 5(1):136–147. https://doi.org/10.23887/jerev5i131712

Erikssen G (2001) Physical fitness and changes in mortality: the survival of the fittest. Sports Med. 31:571–576. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131080-00001

Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P (2002) Relation of perceived emotional intelligence and health-related quality of life of middle-aged women. Psychol. Rep. 91(1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0200291147

Fang YY, Huang CY, Hsu MC (2019) Effectiveness of a physical activity program on weight, physical fitness, occupational stress, job satisfaction and quality of life of overweight employees in high-tech industries: a randomized controlled study. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 25(4):621–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/1080354820181438839

Fernández Ozcorta EJ, Almagro Torres BJ, Sáenz López Buñuel P (2015) Perceived emotional intelligence and the psychological well-being of university students depending on the practice of physical activity. Cultura_Ciencia_Deporte [CCD] 10(28). https://repositorio.ucam.edu/handle/10952/6204

Ferrer-Caja E, Weiss MR (2000) Predictors of intrinsic motivation among adolescent students in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. sport 71(3):267–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367200010608907

Feuerhahn N, Sonnentag S, Woll A (2014) Exercise after work, psychological mediators, and affect: A day-level study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 23(1):62–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X2012709965

Fox S, Spector PE (2000) Relations of emotional intelligence, practical intelligence, general intelligence, and trait affectivity with interview outcomes: It’s not all just ‘G’. J. Organ. Behav.: Int. J. Ind., Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 21(2):203–220. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200003)21:2<203::AIDJOB38>3.0.CO;2-Z

Fütterer T, Waveren LV, Hübner N, Fischer C, Salzer C (2022) I can’t get no (job) satisfaction? Differences in teachers’ job satisfaction from a career pathways perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 121:103942. https://doi.org/10.1016/jtate2022103942

Gacek M, Frączek B (2005) Physical activity as a remedial element in psychological stress reduction among the youth. Ann Univ Marie Curie-Skłodowska Lublin-Polonia. Section D 16(107)):496–499

Gao L, Chen S, Wang H (2015) Young faculty’s job satisfaction and its influencing factors: a survey of young faculty at nighty-four universities in Beijing. Fudan Educ. Forum 13:74–80

Gao S, Zhuang J, Chang Y (2021) Influencing factors of student satisfaction with the teaching quality of fundamentals of entrepreneurship course under the background of innovation and entrepreneurship. Front. Educ. 6:730616. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc2021730616

García-Martínez I, Puertas-Molero P, González-Valero G, Castro-Sánchez M, Ramírez-Granizo I (2018) Fomento de hábitos saludables a través de la coordinación del profesorado de educación física. SPORT TK-Rev. Euroam. de. Cienc. del. Deporte 7(2):21–26. https://doi.org/10.6018/sportk343191

Gentile A, Giustino V, Rodriguez-Ferrán O, La Marca A, Compagno G, Bianco A, Alesi M (2023) Inclusive physical activity games at school: The role of teachers’ attitude toward inclusion. Front. Psychol. 14:1158082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1158082

Gogulla S, Lemke N, Hauer K (2012) Effekte körperlicher Aktivität und körperlichen Trainings auf den psychischen Status bei älteren Menschen mit und ohne kognitive Schädigung. Z. f.ür. Gerontol. Und Geriatr. 45(4):279–289

Goleman D (1995) Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books, New York

González J, Cayuela D, López-Mora C (2019) Prosocialidad, Educación Física e Inteligencia Emocional en la Escuela. J. Sport Health Res. 11(1):17–32

González Valero G, Zurita Ortega F, Puertas Molero P, Espejo Garcés T, Chacón Cuberos R, Castro Sánchez M (2017) Influencia de los factores sedentarios (dieta y videojuegos) sobre la obesidad en escolares de Educación Primaria. ReiDoCrea 6:120–129. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug45233

Gutin B, Johnson MH, Humphries MC, Hatfield‐Laube JL, Kapuku GK, Allison JD, Barbeau P (2007) Relationship of visceral adiposity to cardiovascular disease risk factors in black and white teens. Obesity 15(4):1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby2007602

Gutiérrez Sas L, Fontenla Fariña E, Cons-Ferreiro M, Rodríguez Fernández JE, Pazos Couto JM (2017) Mejora de la autoestima e inteligencia emocional a través de la psicomotricidad y de talleres de habilidades sociales. Sportis 3(1):187–205

Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW (2007) Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 56(11):2655–2667. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-0882

Han J, Perron BE, Yin H, Liu Y (2021) Faculty stressors and their relations to teacher self-efficacy, engagement and teaching satisfaction. High. Educ. Res Dev. 40:247–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/07279436020201756747

Haskell WL (2012) Physical activity by self-report: A brief history and future issues. J. Phys. Act. Health 9(s1):S5–S10. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah9s1s5

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76(4):408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

He T (2015) The effect of college teachers’ social support on job stress and job satisfaction. China J. Health Psychol. 23:712–716

He T, Liu W (2012) The effect of university teachers’ personality on job stress and job satisfaction. J. Health Psychol. 20:1003–1005

Hills AP, Dengel DR, Lubans DR (2015) Supporting public health priorities: Recommendations for physical education and physical activity promotion in schools. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 57(4):368–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpcad201409010

Ho CL, Au WT (2006) Teaching satisfaction scale: Measuring job satisfaction of teachers. Educ Psychol Meas 66(1):172–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405278573

Houston D, Meyer LH, Paewai S (2006) Academic staff workloads and job satisfaction: Expectations and values in academe. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 28(1):17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800500283734

Ignat AA, Clipa O (2012) Teachers’ satisfaction with life, job satisfaction and their emotional intelligence. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 33:498–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/jsbspro201201171

Jacobs JA, Winslow SE (2004) Overworked faculty: Job stresses and family demands. ANNALS Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 596(1):104–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204268185

Jing L (2008) Faculty’s job stress and performance in the undergraduate education assessment in China: A mixed-methods study. Educ. Res. Rev. 3(10):84–87. http://www.academicjournalsorg/ERR

Ju C, Lan J, Li Y, Feng W, You X (2015) The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/jtate201506001

Karim J, Weisz R (2011) Emotional intelligence as a moderator of affectivity/ emotional labor and emotional labor/psychological distress relationships. Psychol. Stud. 56:348–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-011-0107-9

Keefer KV, Parker JD, Saklofske DH (2009) Emotional intelligence and physical health. Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications: 191-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-88370-0_11

Kerr JH, Kuk G (2001) The effects of low and high intensity exercise on emotions, stress and effort. Psychol. sport Exerc. 2(3):173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(00)00021-2

Khassawneh O, Mohammad T, Ben-Abdallah R, Alabidi S (2022) The relationship between emotional intelligence and educators’ performance in higher education sector. Behav. Sci. 12(12):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120511

Kinman G, Jones F (2008) A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance, and wellbeing in UK academics. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 17(1-2):41–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802165478

Klaperski S, von Dawans B, Heinrichs M, Fuchs R (2013) Does the level of physical exercise affect physiological and psychological responses to psychosocial stress in women? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 14(2):266–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpsychsport201211003

Klaperski S, von Dawans B, Heinrichs M, Fuchs R (2014) Effects of a 12-week endurance training program on the physiological response to psychosocial stress in men: A randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Med. 37(6):1118–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9562-9

Klassen RM, Chiu MM (2010) Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 102(3):741. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

Klassen RM, Wilson E, Siu AFY, Hannok W, Wong MW, Wongsri N et al. (2013) Preservice teachers’ work stress, self-efficacy, and occupational commitment in four countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28:1289–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0166-x

Kokkinos CM (2007) Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77(1):229–243. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X90344

Kokkinos P (2008) Physical activity and cardiovascular disease prevention: current recommendations. Angiology 59:26S–29SS. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319708318582

Künsting J, Neuber V, Lipowsky F (2016) Teacher self-efficacy as a long-term predictor of instructional quality in the classroom. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 31:299–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0272-7

Lai M, Du P, Li L (2014) Struggling to handle teaching and research: A study on academic work at select universities in the Chinese mainland. Teach. High. Educ. 19(8):966–979. https://doi.org/10.1080/135625172014945161

Latif H, Majoka MI, Khan MI (2017) Emotional intelligence and job performance of high school female teachers. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 32(2):333–351

Lawlor DA, Hopker SW (2001) The effectiveness of exercise as an intervention in the management of depression: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 322 (7289):763

Lewis GM, Neville C, Ashkanasy NM (2017) Emotional intelligence and affective events in nurse education: A narrative review. Nurse Educ. today 53:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/jnedt201704001

Li H (2005) Development of college working stress scale. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 21:105–109

Li JJ (2018) A study on university teachers’ job stress-from the aspect of job involvement. J. Interdisp. Math. 21:341–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972050220171420564

Li GSF, Lu FJ, Wang AHH (2009) Exploring the relationships of physical activity, emotional intelligence and health in Taiwan college students. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 7(1):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1728-869X(09)60008-3

Li GSF, Li WT, Wang HH (2011) Development of a Chinese emotional intelligence inventory and its association with physical activity. Emotional Intelligence–New Perspectives and Applications 195

Li W, Kou C (2018) Prevalence and correlates of psychological stress among teachers at a national key comprehensive university in China. Int J. Occup. Environ. Health 24:7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1077352520181500803

Liu XP, Zhou YY (2016) Research on the impact of job stress on job satisfaction of college teachers. High. Educ. Explor 1:125–129

Liu Y, Yi S, Siwatu KO (2023) Mediating roles of college teaching self-efficacy in job stress and job satisfaction among Chinese university teachers. Front. Educ. 7:1073454. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc20221073454

Lu C, Buchanan A (2014) Developing students’ emotional well-being in physical education. J. Phys. Educ., Recreat. Dance 85(4):28–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/073030842014884433

Magnini VP, Lee G, Kim B (2011) The cascading affective consequences of exercise among hotel workers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 23(5):624–643. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111143377

Mammen G, Faulkner G (2013) Physical activity and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 45(5):649–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/jamepre201308001

Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P (1999) Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 27(4):267–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00016-1

Mayer JD, Salovey P (1997) What is emotional intelligence? In P Salovey, D Sluyter (Eds) Emotional development and emotional intelligence. Basic Books, New York, p 3-31

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2004) Emotional intelligence: theory, findings, and implications. Psychol. Inq. 15(3):197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

Mayer JD, Roberts RD, Barsade SG (2008) Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59:507–536. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevpsych59103006093646

Meng Q, Wang G (2018) A research on sources of university faculty occupational stress: A Chinese case study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 11:597–605

Mérida-López S, Extremera N, Rey L (2017) Contributions of work-related stress and emotional intelligence to teacher engagement: Additive and interactive effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 14(10):1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101156

Miao C, Humphrey RH, Qian S (2016) A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 90(2):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop12167

Molina-García J, Castillo I, Queralt A (2011) Leisure-time physical activity and psychological well-being in university students. Psychol. Rep. 109(2):453–460. https://doi.org/10.2466/061013PR01095453-460

Moreira-Silva I, Santos R, Abreu S, Mota J (2014) The effect of a physical activity program on decreasing physical disability indicated by musculoskeletal pain and related symptoms among workers: a pilot study. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 20(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548201411077028

Mouton A, Hansenne M, Delcour R, Cloes M (2013) Emotional intelligence and self-efficacy among physical education teachers. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 32(4):342–354. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe324342

Muchhal DS, Solkhe A (2017) An empirical investigation of relationship between emotional intelligence and job performance in Indian manufacturing sector. Clear Int. J. Res. Commer. Manag. 8(7):18–21

Naczenski LM, de Vries JD, van Hooff ML, Kompier MA (2017) Systematic review of the association between physical activity and burnout. J. Occup. Health 59(6):477–494. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh17-0050-RA

Naseem K (2018) Job stress, happiness and life satisfaction: The moderating role of emotional intelligence empirical study in telecommunication sector Pakistan. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Stud. 4(1):7–14

Netz Y, Wu MJ, Becker BJ, Tenenbaum G (2005) Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychol. aging 20(2):272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974202272

Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, Hamilton J, Spruijt-Metz D (2006) Associations between physical activity and perceived stress/hassles in college students. Stress Health.: J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 22(3):179–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi1094

Ni S, Yang R, Wang X (2016) The effect of perceived unwritten roles on job stress of university teachers. Chin. You Soc. Sci. 4:11–16

Norris R, Carroll D, Cochrane R (1992) The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J. Psychosom. Res. 36(1):55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(92)90114-H

Okay DM, Jackson PV, Marcinkiewicz M, Papino MN (2009) Exercise and obesity. Prim. Care: Clin. Off. Pract. 36(2):379–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpop200901008

Oshagbemi T (2003) Personal correlates of job satisfaction: empirical evidence from UK universities. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 30(12):1210–1232. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290310500634

Paluska SA, Schwenk TL (2000) Physical activity and mental health: current concepts. Sports Med. 29:167–180. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200029030-00003

Penedo FJ, Dahn JR (2005) Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr. Opin. psychiatry 18(2):189–193

Petrides KV (2009) Psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue) In C Stough DH, Saklofske JD, Parker (Eds), Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and applications. Springer, p 85–102

Petrides KV, Mavroveli S (2018) Theory and applications of trait emotional intelligence. J Hellenic Psychol Soc 23(1):24–36. https://doi.org/10.12681/psy_hps.23016

Petrides KV, Mikolajczak M, Mavroveli S, Sanchez-Ruiz MJ, Furnham A, Pérez-González JC (2016) Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 8(4):335–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916650493

Puertas Molero P, González Valero G, Sánchez Zafra M (2017) Influencia de la práctica físico deportiva sobre la Inteligencia Emocional de los estudiantes: Una revisión sistemática. ESHPA 1(1):10–24. http://hdlhandlenet/10481/48957

Puertas-Molero P, Zurita-Ortega F, Chacón-Cuberos R, Martínez-Martínez A, Castro-Sánchez M, González-Valero G (2018) An explanatory model of emotional intelligence and its association with stress, burnout syndrome, and non-verbal communication in the university teachers. J. Clin. Med. 7(12):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7120524

Rahm T, Heise E (2019) Teaching happiness to teachers-development and evaluation of a training in subjective well-being. Front. Psychol. 10:2703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg201902703

Rexrode KM, Carey VJ, Hennekens CH, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE (1998) Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. Jama 280(21):1843–1848. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama280211843

Riyadi S (2015) Effect of work motivation, work stress and job satisfaction on teacher performance at senior high school (SMA) throughout The State Central Tapanuli, Sumatera IOSR. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 20(2):52–57. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-20215257

Romero-Martín MR, Gelpi P, Mateu M, Lavega P (2017) Influence of practical driving on emotional state university students. Rev. Int. de. Med. y. Cienc. de. la Actividad F. í Sci. y. el Deporte 17:449–466

Ros M, Moya-Faz FJ, Garcés DLFR (2013) Emotional intelligence and sport: current state of research. Cuad. de. Psicol.ía del. Deporte 13(1):105–112

Roxana Dev OD, Ismi Arif I, Maria Chong A, Soh Kim G (2014) Emotional intelligence as an underlying psychological mechanism on physical activity among Malaysian adolescents. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 19:166–171

Saklofske DH, Austin EJ, Galloway J, Davidson K (2007) Individual difference correlates of health-related behaviours: Preliminary evidence for links between emotional intelligence and coping. Personal. Individ. Differ. 42(3):491–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpaid200608006

Salovey P, Mayer JD (1990) Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 9(3):185–211

Sánchez-Álvarez N, Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P (2015) The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Posit. Psychol. 11(3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743976020151058968

Sánchez-Álvarez N, Extremera N, Fernández-Berrocal P (2016) The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Posit. Psychol. 11(3):276–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743976020151058968

Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J (2006) Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 99(6):323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/joer996323-338

Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, Haggerty DJ, Cooper JT, Golden CJ et al. (1998) Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 25(2):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00001-4

Shi J, Wang L (2007) Validation of emotional intelligence scale in Chinese university students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 43(2):377–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/jpaid200612012

Shin JC, Jung J (2014) Academics job satisfaction and job stress across countries in the changing academic environments. High. Educ. 67:603–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9668-y

Sjösten N, Kivelä SL (2006) The effects of physical exercise on depressive symptoms among the aged: a systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry.: A J. Psychiatry. Late Life Allied Sci. 21(5):410–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps1494

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2011) Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27(6):1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/jtate201104001

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2007) Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. J. Educ. Psychol. 99(3):611. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663993611

Sonnentag S, Venz L, Casper A (2017) Advances in recovery research: What have we learned? What should be done next? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22(3):365–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000079

Sothman MS (2006) The cross-stressor adaptation hypothesis and exercise training In EO Acevedo P Ekkekakis (Eds) Psychobiology of physical activity. Champaign: Human Kinetics, p 149-160

Stathopoulou G, Powers MB, Berry AC, Smits JA, Otto MW (2006) Exercise interventions for mental health: a quantitative and qualitative review. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract. 13(2):179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j1468-2850200600021x

Strawbridge WJ, Deleger S, Roberts RE, Kaplan GA (2002) Physical activity reduces the risk of subsequent depression for older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156(4):328–334. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf047

Ströhle A (2009) Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J. Neural Transm. 116:777–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-008-0092-x

Sun W, Wu H, Wang L (2011) Occupational stress and its related factors among university teachers in China. J. Occup. Health 53(4):280–286. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh10-0058-OA

Szabo A (2003) The acute effects of humor and exercise on mood and anxiety. J. Leis. Res. 35(2):152–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216200311949988

Thompson PD (2003) Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23(8):1319–1321. https://doi.org/10.1161/01ATV000008714333998F2

Tian M, Lu G (2017) What price the building of world-class universities? Academic pressure faced by young lecturers at a research-centered university in China. Teach. High. Educ. 22(3):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251720171319814

Toker S, Biron M (2012) Job burnout and depression: unraveling their temporal relationship and considering the role of physical activity. J. Appl. Psychol. 97(3):699. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026914

Toropova A, Myrberg E, Johansson S (2021) Teacher job satisfaction: the importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educ. Rev. 73(1):71–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191120191705247

Truta C, Parv L, Topala I (2018) Academic engagement and intention to drop out: Levers for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 10(12):4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124637

Tsaousis I, Nikolaou I (2005) Exploring the relationship of emotional intelligence with physical and psychological health functioning. Stress Health.: J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 21(2):77–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi1042

Tytherleigh MY, Webb C, Cooper CL, Ricketts C (2005) Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: A comparative study of all staff categories. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 24(1):41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436052000318569

Ubago-Jiménez JL, González-Valero G, Puertas-Molero P, García-Martínez I (2019) Development of emotional intelligence through physical activity and sport practice A systematic review. Behav. Sci. 9(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9040044