Abstract

This study aimed to explore the forms and causes of domestic violence against women in Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic through a systematic literature review. The review yielded eight articles published between April 2020 and November 2022 in the final sample, all of which met the inclusion criteria. The results revealed 11 forms of domestic violence against women in Jordan during and after the full and partial lockdowns due to the pandemic. Physical violence was the most prevalent form of domestic violence, followed by economic, psychological, emotional, verbal, and sexual forms, as well as control and humiliation, bullying, online abuse, harassment and neglect-related violence. The causes were a combination of economic, socio-cultural, and psychological factors emerging because of the pandemic and lockdowns (e.g., poverty, job loss, low wages, gender discrimination, double burden on women [monotonous roles, paid work], male dominance, reduced income, high cost of living). Additionally, effects of the pandemic included psychological, mental, and emotional negative consequences (e.g., anxiety, fear, stress, depression, loneliness, failure, status frustration). Individuals in Jordanian societies employed the norms, ideas, and values of the patriarchal culture to negatively adapt to the economic and psychological effects of the pandemic, which contributed to more domestic violence cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) is a significant global and social problem. United Nations (2022) defined DV as a pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner, including physical, sexual, psychological, emotional, and financial acts or threats of action that influence another person. DV is also called “domestic abuse,” “family violence” or “intimate partner violence (IPV)” (Xue et al. 2020; Alsawalqa 2021a). “DV is reaching across national boundaries as well as socio-economic, cultural, racial and class distinctions… its incidence is also extensive, making it a typical and accepted behavior… Its continued existence is morally indefensible…” (Kaur & Garg, 2008: p. 73). DV is the most common form of violence against women (Xue et al. 2020). According to UN Women (2021: p. 4), the experiences of violence against women can be classified into several categories: physical abuse (i.e., been slapped, hit, kicked, had things thrown at them, or other physical harm); verbal abuse (i.e., being yelled at, called names, humiliated); denied basic needs (i.e., health care, money, food, water, shelter); denied communication (i.e., with other people, including being forced to stay alone for long periods of time); and sexual harassment (i.e., being subjected to inappropriate jokes, suggestive comments, leering or unwelcome touch/kisses). UN Women used this definition for the purpose of the measuring the impact of COVID-19 on violence against women.

DV as a “shadow pandemic” grew and intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly against women and girls (Women UN 2021). UN women (2021) confirmed there was an increase in calls to DV helplines in many countries since the outbreak of COVID-19. Xue et al. (2020) indicated that during the COVID-19 lockdown, homes became an unsafe environment for victims of DV; women and children were disproportionately affected and made vulnerable during the crisis, which prevented them from seeking help, thus increasing their vulnerability and suffering. The lockdown measures due to the pandemic imposed social distancing, leading to increased family isolation and limited access to legal and social services (Xue et al. 2020; Leslie and Wilson 2020). These socio-economic stressors led to negative emotional, behavioral, and psychological consequences including depression, anxiety, panic, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and paranoia (Pedrosa et al. 2020), and thus facilitated DV, child abuse, and elder abuse (Al-Tammemi 2020; Xue et al. 2020).

Since the first registered case of COVID-19 on March 2, 2020, the Jordanian government took several protective measures to prevent the rapid spread of the virus by implementing the National Defense Law on March 14. Under this law, the roads, schools, universities, air and land border crossings, all private businesses, and non-essential public services were closed. Additionally, this law suspended air traffic, and public gatherings as well as religious practices were banned. These rigorous measures had negative multidimensional effects on the economic and social conditions of Jordanian citizens, including human rights violations, such as labor rights, freedom of expression (Alsawalqa et al. 2022a), loss of human resources, decreased income levels because of declining economic growth, drop in productivity, dismissal of employees from their work, and the inability of some organizations to pay employees’ salaries (Abufaraj et al. 2021; Al-Tammemi 2020). These poor conditions contributed to an increase in DV cases, in particular against women and children. Jordanian Juvenile and Family Protection Department (2020) stated that the number of reports of DV increased from 41,221 in 2018, to 54,743 in 2020; of these cases, 58.7% were physical violence, and 34% sexual violence, and most of the victims were female (Higher Population Council, 2021; National Council for Family Affairs 2022; 2013). According to the United Nations Population Fund, approximately 69% of Jordanian women were victims of some type of gender-based DV during the COVID-19 pandemic (Anderson 2020).

Jordanian women suffering multiple socio-economic constraints was directly related to the economic, social, and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which imposed new obligations on women, consumed more of their time and effort, and increased their stress and responsibility owing to the long period for which they had to stay at home. Homes became increasingly crowded with all members of the family present, thus increasing the household chores and caregiving burden faced by women and also the burden in meeting family needs in terms of food and supervising their children’s online education and recreation activities. Moreover, women also had to ensure that health and safety precautions to protect their family were performed diligently. Additionally, they experienced increasing financial obligations, declining income, and accumulated debt owing to the pandemic (AbuTayeh 2021). Similarly, Sisterhood is Global Institute-Jordan (SIGI) (2021a, 2021b) mentioned that the most important effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women included the burden of unpaid family care; the high risk of women and children being exposed to DV, and the decline in protection, prevention and response services provided to them; the exacerbation of a lack of women’s economic participation, the increase in the requirement of women in the healthcare sector, and the weak representation of women in leadership positions and response teams.

The Jordanian government implemented several measures to address cases of DV and violence against women and girls. These included the establishment of the Family Protection Department in 1997, which was merged with the Juvenile Department in 2021 to become the Juveniles and Family Protection Department (Public Security Directorate 2022). For the first time in Jordan, the principle of promoting gender equality was adopted as an organizing factor in the economic and social development plan (1999–2003), by integrating a gender perspective (The Jordanian National Commission for Women 1998). In addition, the National Council for Family Affairs was established in 2001 as a civil society organization to contribute to formulating and analyzing legislation for senior citizens, family counseling, and for early childhood and family protection against violence; it included the national team for family protection against violence to address the gaps in the protection system for family members and stop incidents of DV. The government also approved the Protection from Domestic Violence Law No. 15 in 2017, in comparison with the Protection from Domestic Violence Law No. 6 of 2008 that can be regarded as a protective law without mention of gender-based violence, Law No. 15 states the importance of adapting legal texts to address the needs of Jordanian families, and to expand the umbrella of family preservation by introducing alternative measures to punishment that could reform the family and enable it to overcome the obstacles it might face (EuroMed Rights, 2018; National Council for Family Affairs 2022; 2013). According to the Secretary-General of the National Council for Family Affairs, this new law gave a broader concept of the place where family members usually reside and expanded the concept of family by adding relatives up to the fourth degree and in-laws from the third and fourth degrees to the list of those covered by the protection law (Protection from domestic violence law, 2017; Al-Nimri 2019). Within the women’s protection system in Jordan, there are five main care homes affiliated with the Ministry of Social Development regarding family harmony for women whose lives are at risk: Dar Al-Wefaq Amman, Dar Al-Wefaq Irbid, Dar Al-Karama, Rusaifa Girls’ Care Home, and Amna. These care homes welcome women whose lives are threatened by honor killings; they wish to end “preventive detention,” in which women whose lives are at risk are referred to prisons in order to preserve their lives (Ministry of Social Development 2022). Regarding government priorities in combating violence against women in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, in March 2020, the Council of Ministers approved the national strategy for women’s empowerment (2020–2025) for a society free from discrimination and gender-based violence, where women and girls can enjoy full human rights and equal opportunities to achieve comprehensive and sustainable development (The Jordanian National Commission For Women 2020).

In spite of the official Jordanian statements about the increase in the number of DV cases against women and girls during the COVID-19 lockdown, the growing momentum of Jordanian media reports on issues of DV against women, and the publication of individual stories of women and girls who have been subjected to physical and psychological violence, murders, or underage marriage of girls (Darwish 2020; Ziyadat 2021; Zoud 2021), the data on DV during the COVID-19 pandemic still remains scarce in Jordan. The reliance on the press and media reports to understand the reasons for this has increased. Therefore, this review aimed to explore the link between the economic, social, and health-related effects of the pandemic and the high number of DV cases against women in Jordan. For this purpose, we explored the forms and causes of DV against women in Jordan, during and after the full and partial lockdowns imposed due to the pandemic, as discussed in the relevant literature.

Method

Sample selection process and search criteria

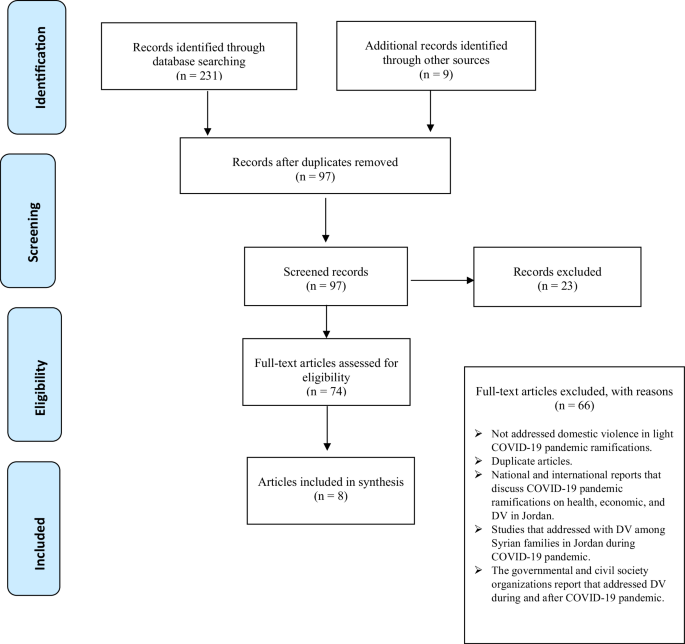

All studies that revealed the forms and causes of DV against women in Jordan during the COVID-19 pandemic, that were published between April 2020 and November 2022, were searched using the University of Jordan Library, PubMed, Google Scholar, and SCOPUS database. We used the following six sets of terms: “gender-based violence” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19,” “partner violence” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19,” “domestic violence” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19,” “domestic abuse” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19,” “women abuse” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19,” and “wife abuse” + “Jordan” + “COVID-19.” The search comprised studies published in Arabic and English in academic journals, which used quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research designs. Primary search results yielded 231 studies. Of these studies, 66 studies were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The systematic review was developed according to the PRISMA (see the flowchart [Fig. 1]).

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. A PRISMA flow diagram visually summarises the screening process. It records the total number of articles found from the initial searches, and then makes the selection process transparent by reporting on inclusion or exclusion decisions made at various stages of the systematic review (Celegence, 2022; Macquarie University Library, 2023).

Data inclusion and exclusion criteria

The primary inclusion criteria for the papers include (a) the presence of DV against women construct, (b) Jordanian society, (c) use of Arabic and English language, (d) published scientific research, and (e) the time range during and after the COVID-19 pandemic between April 2020 and November 2022. This period was identified because it witnessed an increased momentum in scientific research regarding the consequences of the pandemic globally. Papers on DV, especially those about DV in Jordan, experienced stagnation toward the end of 2022. It was observed by the researchers that scientific journals, especially local Jordanian journals, no longer include the repercussions of the pandemic on DV among their priorities and interests in publishing. This was also confirmed through communication with other researchers and publishers.

We also included both qualitative and quantitative articles focusing on constructs connected to DV against women, such as women abuse, wife abuse, partner violence, gender-based violence, domestic abuse, family abuse, and family violence. Studies that examine DV against women in Jordan before the COVID-19 pandemic, and DV against the elderly before the COVID-19 pandemic, or children before or during and after the COVID-19 pandemic were excluded. Additionally, unpublished studies, national and international reports, duplicate articles, master’s and Ph.D. theses, conference abstracts, and studies that included refugee DV against women (e.g. families or Syrian women) in Jordan were also excluded.

After assessing the quality of the primary studies and refining the included studies in the final sample, all eight remaining studies that met the inclusion criteria were exported to EndNote. The data were extracted and sorted through a structured table that contained seven variables: (a) author and publication year, (b) aim, (c) study design, (d) sample details, (e) occurred sample location, (f) definition of DV, (g) forms of DV, (h) causes of DV, (i) abuser, and (j) study limitations (see Table 1).

Quality assessment

The search in the literature via a comprehensive search of bibliographic databases, manual searches, and exploration of grey literature searches contribute to reducing bias. Moreover, the inclusion of studies has been thoroughly reviewed and their eligibility was independently assessed by two sociology professors, A.A and K.B with expertise in the fields of violence and abuse within the Jordanian context. They screened all study titles and abstracts to ensure that the study objectives were adhered to, in collaboration with both researchers M.A and R.A. They then examined the texts of the studies following the systematic review protocol as a guide (PRISMA 2020); R.A and A.A and reviewed the data, and the whole team discussed and agreed on the results of the data. Quantitative studies were assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies, which includes eight categories: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis appropriate to questions. Each examined practice receives a mark ranging between “strong,” “moderate,” and “weak” (Thomas 2003). For qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist) was used, which includes ten questions, answerable with three options (“yes”, “no” or “can’t tell”), to evaluate the study aims, validity of methodology, data analysis and results, research design validity and novelty. The CASP is divided into three sections — Section A: Are the results of the study valid? Section B: What are the results? Section C: Will the results help locally? (CASP website 2022).

Sample description

The eight articles included in the final sample were published between April 2020 and November 2022 in eight separate English-language journals on interpersonal violence, clinical practice, humanities and social sciences, and psychology. Of these super specialty journals and their scope in issues related to violence, only one journal specialized in violence—the Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Most of these studies had a quantitative descriptive design via online survey, and included cross-sectional (four articles), descriptive statistical (two articles), and descriptive comparative (one article) studies. The remaining study adopted qualitative exploratory descriptive analysis through a semi-structured interview guide (one article). Most of the participants in these studies were married women, between 18 and 55 years of age, who had experienced violence from their husbands; a few of them had experienced it from their father, brother, mother, or work colleagues. Only one study addressed DV among pregnant women (Abujilban et al. 2022). Two articles included samples of men: one of them included only married men and explored the causes and forms of DV against their wives from the perspective of the husbands. Most of these studies considered the rural and urban classification in selecting the population samples from the north, central, and southern regions of Jordan (five articles), while three articles selected samples from Amman, the capital of Jordan. No article defined or presented a clear concept of DV, except three articles, one of which was based on the World Health Organization’s definition (Abujilban et al. 2022). The other articles defined DV as any abusive or violent behavior that occurred between spouses. Two articles used the term “intimate partner” to refer to the husband, and some used IPV, “spousal violence,” “women abuse,” and “male violence against women” synonymously with DV (Table 1).

Limitations of the study

The present study is one of the first studies to address DV against women during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan, that is, within an Arab Muslim social- cultural context. The strengths of this review are the focus on the concept of DV used in studies as well as the identity of the abuser. in Jordan (rural, urban/ North, Central, South), with differently ages (18-60 years) and their educational, professional, and marital status, as well as their health status (e.g. pregnant women).

This study enriches the field of family sociology studies and women’s studies in Jordan, considering that the data on DV Against Women during the COVID-19 pandemic are still scarce in Jordan and the reliance on the press and media reports to understand the reasons for this has increased. Nevertheless, the present study also had some limitations. First, it excludes women of other nationalities, such as those who hold Syrian and Iraqi nationality and lived for a period in Jordan and were involved in its cultural context and experienced the same economic conditions, especially during and after the pandemic. Without this exclusion, the study sample could have enhanced the results and presented clearer details on women’s DV experiences in Jordan in general. Second, this review was limited to publications in English and Arabic, and in international and local academic journals only, which means that studies that may have been published in other languages were not considered, and scientific studies conducted by organizations and educational institutions that could have added to causes or forms of violence were not considered. Finally, this study does not consider studies on DV consequences and intervention strategies, which may hinder a complete understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Results

The findings of our review were divided according to the main research goals: exploring forms and causes of DV against Jordanian women during and after the full and partial lockdowns imposed due to the pandemic.

Forms of DV against women during and after the COVID-19 pandemic

The results of our systematic review revealed 11 forms of DV experienced by women and girls in Jordan during and after the full and partial lockdowns due to the pandemic: physical (Abujilban et al. 2022; Abuhammad, 2021; Alsawalqa, 2021a; Alsawalqa, 2021b; Alsawalqa et al. 2021; Kataybeh 2021; Qudsieh et al. 2022), economic (Alsawalqa 2021a; Alsawalqa, 2021b; Qudsieh et al. 2022), psychological (Abujilban et al. 2022; Abuhammad, 2021; Alsawalqa 2021a; Alsawalqa 2021b; Kataybeh 2021), emotional (Alsawalqa, 2021a; Alsawalqa 2021b) verbal (Kataybeh 2021; Qudsieh et al. 2022; Alsawalqa et al. 2021), sexual (Abujilban et al. 2022; Kataybeh 2021), control and humiliation (Abujilban et al. 2022), bullying (Alsawalqa et al. 2021), online abuse (Alsawalqa et al. 2021), harassment (Alsawalqa 2021b), and neglect (Alsawalqa 2021a). Physical violence was the most prevalent among the samples of these studies. Notably, some of these articles dealt with psychological and emotional abuse as belonging to the same category, or as a separate concept [e.g., Qudsieh et al. 2022; Kataybeh 2021]. By contrast, some researchers defined the concepts of verbal, psychological, and emotional abuse, and dealt with them separately [e.g., Alsawalqa 2021b; Kataybeh 2021]. One article addressed DV in general without clarifying its types and measurement; its results simply indicated that “20.5% of the participants suffered from increased domestic abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Aolymat, 2020: 520).

Causes of DV against women during and after the COVID-19 pandemic

We found that the causes of DV Against Women during the pandemic were the result of a combination of the economic, socio-cultural, and psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and curfew. Six articles confirmed that the economic factors included poverty; job loss; low, insufficient, or reduced income; and high cost of living and healthcare facilities, which led to the spread and rise of DV (Abuhammad, 2021; Qudsieh et al. 2022; Alsawalqa, 2021a; Alsawalqa 2021b; Aolymat 2020; Kataybeh 2021). Moreover, the lockdown increased the time spent with partners and family members and caused negative psychological responses, such as stress and tension (Abuhammad, 2021). Five articles emphasized that the main socio-cultural factor that encouraged violence against women was the hegemonic masculinity and patriarchy that normalized violence, making women accept, tolerate, and even justify it (Abuhammad, 2021; Alsawalqa 2021a; Alsawalqa 2021b; Alsawalqa et al. 2021; Kataybeh 2021). Furthermore, the studies showed that the wives’ families often interfered in their marital life (Alsawalqa 2021a; Kataybeh 2021; Alsawalqa et al. 2021). The results of the study Alsawalqa (2021a) also confirmed that the wives’ long preoccupation with social media, and neglect of the house, children, and their personal hygiene, in addition to the husband’s unfulfilled sexual needs, were among the main reasons why they were violent to their wives, before and during the pandemic. All studies indicated that these economic, social, and cultural factors and their negative effects on the psychological, emotional, and social well-being of individuals had long-term effects which continued after the end of the lockdown.

Discussion

Despite the abundance of publications on DV in Jordan, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was no clear or explicit definition of the concept of DV or an accurate distinction of its forms (Alsawalqa et al. 2022b). Our study attempted to shed light on published scientific research that addressed DV in Jordan during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, to gain knowledge and enhance our understanding of the link between the pandemic’s ramifications and high rates of DV in Jordan.

Globally, before the COVID-19 pandemic began, one in every three women experienced physical or sexual violence mostly by an intimate partner; 245 million women and girls aged 15 years or over have been subjected to sexual or physical violence. The violence against women and girls has intensified since the outbreak of COVID-19 (Women UN 2021).

According to World Health Organization (2020: p1) the Eastern Mediterranean Region has the second highest prevalence of violence against women (37%) worldwide. This is due to structural systems that maintain gender inequalities at different levels of society, compounded by political crises and socioeconomic instability in the region. Based on a Women UN (2021) study, in collaboration with Ipsos, and with support from national statistical offices, national women’s machineries and a technical advisory group of experts, the pooled data from 13 countries covering more than 16,000 women respondents, found that 1 in 4 women say that household conflicts have become more frequent, and they feel more unsafe in their home, and (58%) women have experienced or know a woman who has experienced violence since COVID-19. The most common form is verbal abuse (50%), followed by sexual harassment (40%), physical abuse (36%), denial of basic needs (35%) and denial of means of communication (30%). Additionally, (56%) women felt less safe at home since the COVID-19 pandemic. (44%) women living in rural areas, were more likely to report feeling more unsafe while walking alone at night since the pandemic, compared to women living in urban areas (39%). (62%) were also more likely to think that sexual harassment in public spaces has worsened, compared to (55%) of women living in urban areas. Moreover, younger women aged 18–49 years were the more vulnerable group, with nearly 1 in 2 of them affected, and more than 3 in 10 women (34%) aged 60+ and more than 4 in 10 women aged 50–59 years (42%) reported having experienced violence or knowing someone who has since the pandemic began. Women living with children were more likely to report having experienced violence or to know someone who has experienced it since the pandemic, whether they were partnered (47%) or not (48%). Conversely, nearly 4 in 10 women living without children, partnered (37%) or not (41%), reported such experiences. Women who were not employed during the pandemic were also particularly affected, with an estimated (52%) reporting such experiences, compared to (43%) of employed women. Additionally, exposure was highest among women in Kenya (80%), Morocco (69%), Jordan (49%) and Nigeria (48%). Those in Paraguay were the least likely to report such experiences, at (25%) (p. 5-6, 8).

In Jordan, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic and the strict lockdown measures to prevent its spread had negative economic, social, and psychological effects on the citizens. Regarding economic repercussions, according to Raouf et al. (2020), the Jordanian gross domestic product decreased by (23%) during the lockdown. The service sector was the hardest hit, seeing an estimated drop in output of approximately (30%), and food systems experienced a reduction in output of approximately (40%). Moreover, employment losses during the lockdown were estimated at over (20%), mainly driven by job losses in the service and agriculture sectors. Household incomes decreased on average by approximately one-fifth owing to the lockdown, mainly driven by contraction in the service sector, slowdown in manufacturing, and lower remittances from abroad. As a result of this lockdown and company exploitation of the National Defense Law’s decisions imposed in emergency situations to ensure protect public safety, many workers were dismissed, several others did not receive their salaries, and some workers’ incomes decreased by (30–50%). Additionally, some companies and organizations deducted the period of lockdown imposed by the government from workers’ salaries (Jordan Labor Watch 2020; Jordan Economic Forum 2020).

The unemployment rate during the fourth quarter of 2019 reached (19%), an increase of (0.3%) from the fourth quarter of 2018. Unemployment rates reached (24.7%) in 2020 and (25%) during the first quarter of 2021, reflecting an increase of (5.7%) from the first quarter of 2020. The rate in the fourth quarter of 2021 reached (23.3%), an increase of (0.1%) from the third quarter of the same year, and a decrease of (1.4%) from the fourth quarter of 2020 (Department of Statistics 2021; 2020). Additionally, self-isolation measures and lockdown policies led to a lack of access to adequate healthcare services (Alijla 2021), particularly restricting women’s access to healthcare (Jordanian Economic and Social Council 2020a, 2020b). There were also increases in food prices and people getting into debt (UNDP 2020).

According to the latest survey on household income and expenditures conducted by the Department of Statistics (2017-2018) (Department of Statistics, Jordan [DOS], 2018), poverty in Jordan was relatively high. It reached (15.7%), representing 1.069 million Jordanians, while the rate of (extreme) hunger poverty in Jordan reached (0.12%), which is equivalent to 7993 Jordanian individuals. Poverty in Jordan increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic; the estimates of the World Bank showed that the potential increase in the short-term poverty rates in Jordan may increase by an additional (11%) over the official rate declared before the COVID-19 pandemic (15.7%), to approximately (27%) (Baybars 2021). A UNICEF study (2020), which covered both Jordanian and Syrian families, also found that the number of households with a monthly income of less than 100 JD (140 USD) had doubled since before the COVID-19 pandemic, and only (28%) of households had adequate finances to sustain themselves for a two-week period. Four out of ten families were unable to purchase the hygiene products they need; children went to bed hungry in (28%) of the homes during lockdown, decreasing to (15%) post-lockdown. As a result of the pandemic, employment was disrupted in (68%) of households. Furthermore, (17%) of the children under five years did not receive basic vaccinations, (23%) of children who were sick during the pandemic did not receive medical attention (largely owing to fear of the virus and lack of funds), eight out of 10 households adopted negative coping strategies, and (89%) of young women performed household duties (including caring) compared to (49%) of young men.

Notably, The Jordan Economic Monitor report issued by the World Bank showed that economic growth in Jordan in 2021 was strong at (2.2%), owing to the significant expansions in the service, industry, and travel and tourism sectors. However, some sectors, such as the service sector that deals directly with the public (through restaurants, hotels, and so on) were still experiencing low levels of economic growth before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (Refaqat et al. 2022). The termination of worker services in affected organizations and businesses had a significant impact on the economic circumstances of many families, particularly women-led households, causing health and psychological harm due to the inability to ensure general well-being and access to effective healthcare. Additionally, women working in low-wage, informal, temporary, or short-term sectors, such as seasonal jobs or small-scale businesses, were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Furthermore, (35.4%) of Jordanian women who worked in the education sector had to switch to remote teaching because of the pandemic, which added to their domestic work. By contrast, (13.4%) of women in Jordan who worked in the health and social services sectors continued to provide their services along with the burdens of social responsibilities imposed on them (Jordanian Economic and Social Council 2020a, 2020b).

Regarding social and psychological repercussions, the negative economic conditions, in addition to the lockdowns, social distancing behaviors, and the lack of in-person social interaction, created enormous pressures that led to high levels of anxiety, stress, and depression among the Jordanian people, particularly among those aged 18–39 years. The stress was greater in men than in women, and anxiety and depression levels were higher in women than in men (Abuhammad et al. 2022). People with poor social support, who were younger and female, were more likely to experience lockdown-related anxiety (Massad et al. 2022). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic had a notable effect on the mental health of the Jordanians who had low monthly income (<500 JD) or were unemployed, as well as diabetes patients (Suleiman et al. 2022), who felt neglected or lonely. Married couples with higher income were less likely to feel lonely than others (Jordanian Economic and Social Council, 2020a, 2020b). Gresham et al. (2021) found that COVID-19-related stressors (financial anxiety, social disconnection, health anxiety, COVID-19-specific stress, and so on) were associated with greater IPV during the pandemic. Additionally, IPV was associated with movement outside of the home (leaving the residence); greater movement outside the home may act as a way for victims to physically distance themselves from their partners, thereby reducing stress and avoiding further abuse.

These negative socio-economic effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led to exacerbating DV among Jordanian families. During the mandatory curfew, (35%) of Jordanians were subjected to at least one form of domestic abuse (10% total increase), (58%) of which were victims of abuse by a male family member (25% father, 16.5% husband, and 16.5% brother), (33%) by a female family member (25% mother, 8% sister), and (9%) by others. The most prevalent forms of DV reported during the lockdown were verbal violence (48%), psychological violence (26%), neglect (17%), and physical abuse (9%). These violent acts (between March 21st to April 26th, 2020) occurred 1–3 times among (75%) of the COVID-19 domestic abuse victims, 4–6 among (19%), and (7+) times among (7%) (Center for Strategic Studies-Jordan 2020). Additionally, since the beginning of 2021 until November 23, 2021, 15 family murders were reported (Sisterhood is Global Institute-Jordan 2021b).

Jordanian husbands confirmed that poverty, insufficient salary, wives’ money spending habits and not considering the negative economic effects of COVID-19 on their work led to their abusive behavior and violent response (Alsawalqa 2021a). The patriarchal structure in the Jordanian society requires men to adhere to masculine standards and ideals of “true manhood,” which require men to be strong, independent, emotionally restrained, tough, and assume responsibility for leadership, family care, and financial support, given that they occupy a higher rank than women. Masculinity has social advantages and entitlements, the most prominent of which are male control, ownership, and dominance. If men are unable to achieve these standards, society can confront them with humiliation, marginalization, stigmatization, and blame (particularly from their wives). This can make them feel shame, disgrace, sadness, depression, failure, status frustration, anxiety, fear of the future, and low self-esteem. Couples express these negative feelings through aggressive and violent behaviors (Alsawalqa et al. 2021; Alsawalqa and Alrawashdeh 2022).

Additionally, some wives (working and non-working) were unable to repay their loans, especially their loans from microfinance institutions. These financial institutions provide loans and financial facilities to specific economic sectors (such as agriculture) and groups of the population (such as women, the poor, and artisans). These institutions have been excessive in lending to women for consumption purposes at the expense of productive projects and have been unable to lift women out of poverty and empower them economically. Owing to the existence of a major defect in the legislative system, lending conditions, and the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, women borrowers (known as “female debtors,” or Algharimat in Arabic) were subjected to legal accountability and imprisonment if they failed to pay back the debt (Jordanian Economic and Social Council 2020b). Notably, some husbands or fathers forced their wives to borrow because of poverty by dominating or exercising coercive control over the women; some women borrowed voluntarily with the aim of improving the family income. If women refuse to contribute to the household income or borrow money, they can face physical, verbal, psychological, and economic abuse.

Moreover, if women borrow money (which subjects them to legal accountability) without the knowledge of her husband or male guardian, it can expose them to more violence, because men can consider this act as a violation of their control which can cause a scandal or encourage stigma (Sa’deh, 2022). Jordanian working women who are married and live in rural and urban areas have encountered spousal economic abuse through control of their economic resources, management of their financial decisions, and exploitation of their economic resources. Moreover, they have endured emotional, psychological, and physical abuse, and harassment as tactics by husbands to reinforce their economic abuse and maintain control over them (Alsawalqa 2021b). Peterman et al. (2020) indicated that the increased violence against women and children during the pandemic was associated with economic insecurity and poverty-related stress, lockdowns, social isolation, exploitative relationships, and reduced health and domestic support options.

The Information and Research Center - King Hussein Foundation (IRCKHF) and Hivos report (2020: p. 4, 14) on the double burden of women in Jordan during COVID-19, showed that in times of disease outbreaks, most women take up greater responsibilities and are often overburdened with paid and unpaid work, which impacts their overall well-being. Unpaid work within the home, sometimes referred to as reproductive work, includes a variety of tasks such as childbearing and caring, preparing meals, cleaning, doing laundry, maintaining the house, and taking care of older adults or disabled family members, among others. Although paid work is tied to a monetary value, unpaid work is usually not recognized as “real work”. Moreover, the new e-learning systems resulted in parents, especially mothers, spending a lot of time ensuring that their children were learning and following up on their schoolwork. Some parents worried about the future of their children’s education; the closure of schools and nurseries created an additional burden for working parents who had to find childcare solutions while they went to work. These additional burdens created new psychological pressures and increased the problem of violence among family members. Married Jordanian women, particularly those who work and are educated, often face conflicts in the economic, political, and socio-cultural aspects (Alsawalqa 2016). Moreover, they experience Marriage and emotional burnout that worsens with the increase in the number of children, which negatively affects their health and leads to headaches, eating disorders, irregular heart rate, stomach pain, and so on (Alsawalqa, 2019; Alsawalqa, 2017). These problems contribute to a higher marriage burnout rate among spouses, particularly among those who work full-time jobs, have been married for ≥ 10 years, and have children. Marriage burnout is a painful state of emotional exhaustion, with physical and emotional depletion experienced by spouses. This state results from emotional exhaustion, work exhaustion, and failure to fulfill the requirements (particularly emotional requirements) of the marriage (Alsawalqa 2019).

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic did not create new motives for DV in Jordan but contributed to its negative economic and psychological repercussions in exacerbating and confirming the pre-existing motives. The patriarchal structure and gender stereotypes in Jordanian society that establish the relationships between men and women based on coercive control produced prejudices that led to social injustice and gender inequality and made both sexes victims of DV. Individuals in Jordanian societies employed the norms, ideas, and values of the patriarchal culture to negatively adapt to the adverse economic and psychological effects of the pandemic, leading to more cases of DV.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the weak economic and social structures in place before the crisis and their negative impact during the pandemic, such as women’s poor economic participation, the gender gap in the labor market, high income tax, high cost of living, administrative and financial corruption, a weak labor market and infrastructure, and high rates of unemployment and poverty. This study highlighted the need for serious participatory work from the government and civil society organizations based on scientific research and approaches to change the cultural and social norms that reinforce patriarchal domination and stereotypes that perpetuate the gender gap. One way of achieving this is through the educational curricula in schools and universities; educating individuals on how to deal with life pressures; choosing a life partner; understanding the motives for marriage and the foundations for successful and healthy relationships, and raising children; and positive social self-development. We recommend supporting the efforts of the Jordanian government to continue the process of development and diligently follow up on the implementation of the directives and vision of His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein, King of Jordan, on economic, political, and administrative reform, activating the role of youth and empowering women. We realize that social and cultural change, and the reforming of sectors is not an easy task and requires tremendous efforts over a long period.

Implications of the study

Considering the current study results, a follow-up study to highlight the lack of conceptual clarity on DV Against Women and its various forms is recommended. Future research must carefully study the behaviors involved in each form of DV and identify the abuser of women as this will help in developing effective policies and practices to reduce or end DV against women. In addition, it would contribute to directing researchers via a correct scientific methodology as they study women’s resistance to violence, and educating women to understand forms of violence and seek the most appropriate resistance strategies to reduce or end it, and avoid involvement in the cycle of violence. Moreover, we recommend paying attention to conducting more studies on DV against males by their wives, mothers, or intimate partners, and DV against the elderly, which will contribute to understanding the factors and forms of domestic violence in more detail. We believe that these aforementioned suggestions will aid in formulating the best intervention strategies.

To reduce DV in Jordan, it is necessary to implementing courses and workshops for women, girls, and males, especially in rural areas, aiming to increase their awareness about the motives for marriage and the foundations of choosing a suitable partner, how to manage emotions, and resist and reduce violence. Additionally, promoting anti-gender discrimination thinking in educational curricula in universities and schools. Moreover, remove obstacles in implementing the Law on Protection from DV, and not to waive personal rights in crimes of DV. In addition, rehabilitation for victims and perpetrators of violence.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

AbuTayeh AM (2021) Socio-economic constraints Jordanian women had encountered as a result of COVID-19 pandemic, and coping mechanisms. Asian Soc Sci 17:63–76. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v17n10p63

Abufaraj M, Eyadat Z, Al-Sabbagh MQ, Nimer A, Moonesar IA, Yang L et al. (2021) Gender-based disparities on health indices during COVID-19 crisis: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Jordan. Int J Equity Health 20:91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01435-0

Abuhammad S (2021) Violence against Jordanian women during COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Clin Pract 75:e13824. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13824

Abuhammad S, Khabour OF, Alomari MA, Alzoubi KH (2022) Depression, stress, anxiety among Jordanian people during COVID-19 pandemic: A survey-based study. Inf Med Unlocked 30:100936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imu.2022.100936

Abujilban S, Mrayan L, Hamaideh S, Obeisat S, Damra J (2022) Intimate partner violence against pregnant Jordanian women at the time of COVID-19 pandemic’s quarantine. J Interpers Violence 37:NP2442–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520984259

Alijla A (2021) Possibilities and challenges: Social protection and COVID-19 crisis in Jordan. Civ, 1. https://doi.org/10.28943/CSKC.002.90003

Al-Nimri N (2019). Adoption of national legislation to strengthen the family and child protection system: The amended Domestic Violence Protection Law is among the most prominent national social achievements. Al Ghad. [Accessed 10 February 2022]. https://alghad.com/

Alsawalqa RO (2021a) A qualitative study to investigate male victims’ experiences of female-perpetrated domestic abuse in Jordan Curr Psychol 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01905-2

Alsawalqa RO, Al Qaralleh AS, Al-Asasfeh AM (2022a) The Threat of the COVID-19 Pandemic to Human Rights: Jordan as a Model. J Hum Rights Soc Work 7:265–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-021-00203-y

Alsawalqa RO (2021b) Women’s abuse experiences in Jordan: A comparative study using rural and urban classifications. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8:186. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00853-3

Alsawalqa RO, Alrawashdeh MN, Sa’deh YAR, Abuanzeh A (2022b) Exploring Jordanian women’s resistance strategies to domestic violence: A scoping review. Front Socio. 7:1026408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.1026408

Alsawalqa RO, Alrawashdeh MN, Hasan S (2021) Understanding the Man Box: The link between gender socialization and domestic violence in Jordan. Heliyon 7:e08264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08264

Alsawalqa RO, Alrawashdeh MN (2022) The role of patriarchal structure and gender stereotypes in cyber dating abuse: A qualitative examination of male perpetrators experiences. Br J Socio 73:587–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12946

Alsawalqa R (2016) Social change and conflict of values among educated women in Jordanian society: A comparative study. Dirasat Hum Soc Sci 43:2067–93

Alsawalqa RO (2017) Emotional burnout among working wives: Dimensions and effect. Can Soc Sci 13:58–69

Alsawalqa RO(2019) Marriage burnout: When the emotions exhausted quietly quantitative research Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 13:e68833. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.68833

Anderson K (2020) Daring to Ask, Listen, and Act: A Snapshot of the Impacts of COVID-19 on Women and Girls’ Rights and Sexual and Reproductive Health [Report]. United Nations Fund for Population Activities, Geneva, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/20200511_Daring%20to%20ask%20Rapid%20Assessment%20Report_FINAL.pdf

Aolymat I (2020) A cross-sectional study of the impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence, menstruation, genital tract health, and contraception use among women in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 104:519–25. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1269

Al-Tammemi AB (2020) The battle against COVID-19 in Jordan: An early overview of the Jordanian experience. Front Public Health 8:188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00188

Baybars S (2021) The World Bank: Corona’s Repercussions Have Raised the Poverty Rate in Jordan. https://alghad.com. [Accessed 10 February 2022]

Celegence (2022) PRISMA flow diagram – CAPTIS™ features. https://www.celegence.com/prisma-flow-diagram/. Accessed May 2022

Center for Strategic Studies-Jordan (2020). Coronavirus lockdown exacerbating domestic violence in Jordan. Jordan’s barometer: The pulse of the Jordanian street– (20). Hivos [Study]. https://www.cawtarclearinghouse.org/

Darwish R (2020) 2020 Was Not a Perfect Year for Jordanian Women. https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-55468564. [Accessed 10 February 2022]

Department of Statistics, Jordan [DOS] (2018) Jordan population and family and health survey 2017–18: key indicators. DOS and ICF, Amman, Jordan, and Rockville, MD, USA, http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/linked-html/DHS2017_en.pdf

Department of Statistics (DoS) (2020) Unemployment Rate During the First Quarter of 2020 – Official Report. http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/unemp_q12020

Department of Statistics (DoS). (2021). Unemployment Rate During the First Quarter of 2021 –official Report. http://dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/archive/unemp/2021/Emp_Q12021.pdf

EuroMed Rights (2018) Situation Report on Violence against Women: Legislative Framework. Report Online, Retrievedِ April 2020. https://euromedrights.org

CASP website (2022).CASP Checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research. Retrieved May 2022. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Gresham AM, Peters BJ, Karantzas G, Cameron LD, Simpson JA (2021) Examining associations between COVID-19 stressors, intimate partner violence, health, and health behaviors. J Soc Personal Relat 38:2291–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211012098

Higher Population Council (HPC) (2021) Jordan joins the world in commemorating the International Day of Non-Violence. https://www.hpc.org.jo/en/content/jordan-joins-world-commemorating-international-day-non-violence. [Accessed 10 February 2022]

IRCKHF and Hivos (2020) COVID-19 and the Double Burden on Women in Jordan. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands [Report], Hivos, https://irckhf.org/projects/covid-19-and-the-double-burden-on-women-in-jordan/

Jordan Economic Forum (2020) Unemployment in Jordan: Reality, expectations and proposals. https://soundcloud.com/jordaneconomicforum-jef/5xedpqmblc51

Jordan Labor Watch J (2020) Unprecedented Challenges for Workers in Jordan: A Report on the Occasion of International Labor Day. http://phenixcenter.net/

Jordanian Economic & Social Council (2020a) Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Roles and Violence Against Women -Results from Jordan [Study]. Amman, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. https://jordan.un.org/

Jordanian Economic & Social Council (2020b). Gender-related impacts of Coronavirus pandemic in the areas of health, domestic violence and the economy in Jordan. Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Amman. https://jordan.unwomen.org/

Jordanian Juvenile and Family Protection Department (2020). Digital statistics. https://www.psd.gov.jo/en-us/content/digital-statistics/. [Accessed 10 February 2022]

Kataybeh Y (2021) Male Violence Against Women: An Exploratory Study of Its Manifestations, Causes, and Discrepancies over Jordanian Women under Corona Pandemic. Preprints 1. https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/pt/ppzbmed-10.20944.preprints202104.0695.v1?lang=en

Kaur R, Garg S (2008) Addressing domestic violence against women: an unfinished agenda. Indian J Community Med: official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine 33(2):73–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.40871

Leslie E, Wilson R (2020) Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. J Public Econ (2020) 189:104241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241

Macquarie University Library (2023) Systematic reviews: PRISMA flow diagram & diagram generator tool. https://libguides.mq.edu.au/systematic_reviews/prisma_screen. Accessed May 2024

Massad I, Al-Taher R, Massad F, Al-Sabbagh MQ, Haddad M, Abufaraj M (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: Early quarantine-related anxiety and its correlates among Jordanians. East Mediterr Health J 26:1165–72. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.20.115

Ministry of Social Development (2022) Care homes for family harmony for women whose lives are at risk. http://mosd.gov.jo

National Council for Family Affairs (2013). Socioeconomic characteristics of domestic violence cases [Study]. [Accessed 10 February 2022]. https://ncfa.org.jo/uploads/2020/07/ab0d5083-3d7e-5f1feb76ebd1.pdf

National Council for Family Affairs. (2022). Domestic violence in Jordan: Knowledge, reality. Trends. [Accessed 10 February 2022]. https://ncfa.org.jo/uploads/2020/07/38ceffed-d7a4-5f1ffdb3f907.pdf

Pedrosa AL, Bitencourt L, Fróes ACF, Cazumbá MLB, Campos RGB, de Brito SBCS et al. (2020) Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 11:566212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212

Peterman A, Potts A, O’Donnell M, Thompson K, Shah N, OerteltPrigione S, et al. (2020). Pandemics and violence against women and children. Center for Global Development Working Paper 528. http://iawmh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/pandemics-and-vawg-april2.pdf. [Accessed 24 September, 2022]

PRISMA (2020) The NEW Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) website. https://www.prisma-statement.org. Retrievedِ february 2021

Public Security Directorate (2022) Juvenile and Family Protection Department. https://www.psd.gov.jo/en-us/psd-department-s/family-and-juvenile-protection-department/. Accessed 10 February 2022

Qudsieh S, Mahfouz IA, Qudsieh H, Barbarawi LA, Asali F, Al-Zubi M et al. (2022) The impact of the coronavirus pandemic curfew on the psychosocial lives of pregnant women in Jordan. Midwifery 109:103317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103317

Raouf M, Elsabbagh D, Wiebelt M (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the Jordanian Economy: Economic Sectors, Food Systems, and Households (Projest Paper). The International Food Policy Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.134132

Refaqat S, Janzer-Araji A, Mahmood A, Kim J (2022) Jordan economic Monitor. Spring. DC: World Bank Group. (2022): Global Turbulence Dampens Recovery and Job Creation (English).Jordan Economic Monitor, Washington, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099410007122222740/IDU05823c2b70646004a400b9fa0477cea7736a4

Sa’deh Y (2022) Economic abuse from a gender perspective: A qualitative study on female debtors “Algharimat” in Jordan [unpublished Master’s thesis]. Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, Qatar

Sisterhood is global institute-Jordan (SIGI) (2021a). What do the Numbers tell us about Injuries and Deaths: An Analytical Reading from a Gender Perspective (Facts Paper). [Accessed 12 March 2022]. https://www.sigi-jordan.org/?p=10613

Sisterhood is global institute-Jordan (SIGI). (2021b). 47% of Women in Jordan Have Their Voices Unheard and Their Sufferings Unseen with Regard to Domestic Violence [Report] https://www.unicef.org/jordan/media/3041/file/Socio%20Economic%20Assessment.pdf

Suleiman YA, Abdel-Qader DH, Suleiman BA, Suleiman AH, Hamadi S, Al Meslamani AZ (2022) Evaluating the impact of COVID-19 on mental health of the public in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res 10:196–205. https://doi.org/10.56499/jppres21.1191_10.2.196

The Jordanian National Commission for Women (2020). National strategy for women in Jordan (2020–2025). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1309642?ln=en

The Jordanian National Commission for Women, (1998). A preliminary report on the implementation of the Beijing Approach. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1309642?ln=en

Thomas, H (2003). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Effective public health practice project. Hamilton, ON, Canada: McMaster University. https://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality%20Assessment%20Tool_2010_2.pdf

UNDP (2020). COVID-19 Impact on Households in Jordan: A rapid assessment. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/arabstates/UNDP-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Households-General-21-FINAL-21-May.pdf. [Accessed 10 February 2022]

UNICEF (2020). Socio-Economic Assessment of Children and Youth in the time of COVID-19. Jordan Publishing [Study]. https://www.unicef.org/jordan/media/3041/file/Socio%20Economic%20Assessment.pdf

United Nations. (2022). What is domestic abuse? https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse [Accessed 12 March 2022]

Women UN (2021). Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19 [Report]. https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/Measuring-shadow-pandemic.pdf. [Accessed 12 March 2022]

World Health Organization (2020) COVID-19 and violence against women in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Report Online, Retrieved February 2022. https://pmnch.who.int/docs/librariesprovider9/meeting-reports/covid-19-and-violence-against-women-in-emro.pdf?sfvrsn=970ca82e_3

Xue J, Chen J, Chen C, Hu R, Zhu T (2020) The hidden pandemic of family violence during COVID-19: Unsupervised learning of tweets. J. Med Internet Res 22:e24361. https://doi.org/10.2196/24361

Ziyadat A (2021) Domestic violence: Murders rise in Jordan during Corona. The New Press, Arab, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/society/

Zoud B (2021). How did Corona raise the rate of Child marriage in Jordan? Ammannet. https://tinyurl.com/yz5549an. [Accessed 12 March 2022]

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Editage (www.editage.com) for their help with English language editing, and proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, MA, ROA; Methodology, MA, ROA, AA, RA; Resources, MA, ROA, AA, RA, FA; Writing—original draft preparation, MA, RA, AA; Writing—review and editing, All authors; Project administration MA, ROA. Correspondence to ROA. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alrawashdeh, M.N., Alsawalqa, R.O., Aljbour, R. et al. Domestic violence against women during the COVID19 pandemic in Jordan: a systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 598 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03117-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03117-y